The Spiritual Side of Life

Science and art are not as distant from one another as it might seem. I suggest that one of the reasons “science nerds” also tend to be the “fantasy nerds” is that they are attracted to the same thing: fantastical worlds full of myriad laws and multifarious beings, whose interactions cannot be determined in advance, and rather must be determined by examination. It begins with creation, the effusive production of color and light and drama that characterizes a world, — real or imagined. J. R. R. Tolkien’s prodigious mind is praised when we study his world of geography, languages, peoples, customs and culture. So too is the real universe. C. S. Lewis converted when he realized that the story of the world was simply a true myth. Fantasists create imaginary fantasy worlds; God creates a real fantasy world.

Science and art are not as distant from one another as it might seem. I suggest that one of the reasons “science nerds” also tend to be the “fantasy nerds” is that they are attracted to the same thing: fantastical worlds full of myriad laws and multifarious beings, whose interactions cannot be determined in advance, and rather must be determined by examination. It begins with creation, the effusive production of color and light and drama that characterizes a world, — real or imagined. J. R. R. Tolkien’s prodigious mind is praised when we study his world of geography, languages, peoples, customs and culture. So too is the real universe. C. S. Lewis converted when he realized that the story of the world was simply a true myth. Fantasists create imaginary fantasy worlds; God creates a real fantasy world.

Science, then, is another aspect of this fantastical impulse. It is the investigation of the real, mythical world in which we live; and such investigation and delight is praise of the maker of the world. Science gets its bad name from reductionism. Scientists, it goes, are dangerous to the faith because they invoke matter in order to reject everything else. Scientists invoke science in order to reject mystery, wonder, and profound truth. I submit that such scientists are lying. One only has to look at their words in unguarded moments to find the truth: in science they find mystery, meaning, harmony and wonder. Sure, when called out they claim that their point is that science alone can provide for the deeper impulses of religion, but the point is that they embrace, rather than reject, the deeper impulses of religion. Their mistake is to misidentify the source of those impulses.

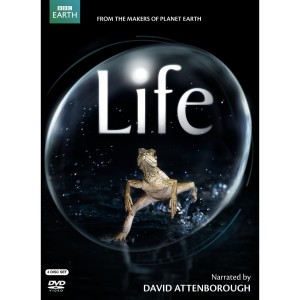

And so it is that we find such artistic productions as the BBC’s simply-titled epic, Life . The series Life is now available on DVD and on Blu-ray. My wife and I have spent the past week watching the episodes nightly. I heartily recommend that viewers purchase the version narrated by the BBC’s legendary naturalist Sir David Attenborough. The Beeb seems to think that Americans need a softer, feminine guide to nature, enlisting Sigourney Weaver as narrator for the American version of Planet Earth, and choosing to invoke the sensitive guru of American spirituality, Oprah Winfrey, as narrator for the American version of Life. I suggest viewers forego the attempted concession to colonial backwardness and select instead the full-blooded Attenborough version. Sir David’s unfeigned and child-like wonder at the natural world (which he intimately knows) is far preferable to the cultured and comfortable distance of the feminine American narrator’s voices.

Like its bestseller predecessor Planet Earth, the epic Life presents the natural world in anthropomorphic terms. The goal of Life’s presentation is not the dull precision of the workaday scientific journal, but the drama of survival, reproduction, and death. Where Planet Earth presented these same themes arranged according to location and climate, Life instead presents them according to kind. We see an episode dedicated to reptiles, an episode dedicated to fish, an episode dedicated to mammals, and so forth. The question is: how do these kinds survive in the cutthroat world of nature? What tools and tricks does each group have? What are the wondrous designs we find in the natural world around us? These are the questions that fascinate the makers of Life and its television cousins.

In the artistic presentation of nature is a certain danger, namely the importation of an agenda. We may portray the climate as warming or cooling or settled to suit our political goals. We may portray gorillas as particularly man-like, or particularly animal-like, so as to prove that they are or are not like us. Yet this danger is no less present in pure art. We may present the climate, or gorillas, simply as they are. The core of the attraction remains the same. Man makes art and calls other men to look at it. God makes art — His art is the whole universe — and also calls all men, and especially the scientists, to look at it. Life and its cinematic cousins are fascinating to the intellectual human watcher. We love to learn about nature and the world around us. Nature is amenable to the human mind. This is because we ourselves are part of nature; it is also because we are images of rational, creative God. The call to art and the call to science are in this way similar: we seek to understand and portray reality as it is.

Given Sir Attenborough’s skeptical tendencies, the materialist position is implicit in Life’s view of the world. Yet watching Life, and its counterparts, such as Planet Earth, the believer is not challenged by evidence of godlessness, but rather ennobled by evidence of godly Providence. Where the atheist sees the coincidental arrangement of the natural world, the believer sees purposeful arrangement. Things are as they are; it is the philosophical and theological reading that determines their meaning. Does ordered nature present an argument for chance or an argument for design? The viewer of Life may decide for himself.