St. Jerome and the Text of Scripture

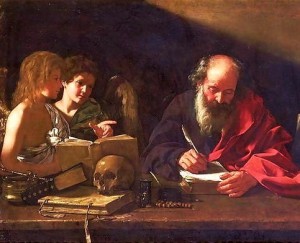

September 30, 420 saw the death of the Latin Church Father St. Jerome and hence September 30th is his feast day. Jerome spent the last half of his life rendering the Scriptures into the contemporary Latin of his day. Since Latin was at that time, the common or “vulgar” tongue, his translation was called the “Latin Vulgate.”

September 30, 420 saw the death of the Latin Church Father St. Jerome and hence September 30th is his feast day. Jerome spent the last half of his life rendering the Scriptures into the contemporary Latin of his day. Since Latin was at that time, the common or “vulgar” tongue, his translation was called the “Latin Vulgate.”

Latin texts of the Scriptures were known from the infancy of the Church. But by Jerome’s time, many variations had crept into the various available Latin versions of the New Testament. Pope Damasus I committed to Jerome the task of organizing and revising the Latin versions and consolidating them so as to create an authenticated text that corresponded with the best attested Greek manuscripts available.

It would be useful at this point to consider a common misconception about the accuracy of the biblical text. One sometimes hears people say, “The Bible was copied and recopied so much that no one could know what it really said.” Let’s engage in a thought experiment for a minute — and anytime anyone says this, you might ask him to do the same.

What if you had a roomful of 20 people and you gave them all a copy of some text like the Gettysburg Address and asked them to copy it by hand? Would they all copy it correctly? Probably not. Might everyone of them make errors? That is very likely. But would any two of them make the same errors? Highly unlikely. Now once you had collected all the copies together, would you be able to reproduce the original text from them? Of course, you would. All you would have to do is look for the majority readings wherever there was a discrepancy. The more texts you have to work with, the easier the job (we call this work “textual criticism”) would be. So the number of copies of parts of Sacred Scripture does not in anyway tell against its accuracy, rather it gives scholars amazing testimony to the inspired Word of God especially compared to other ancient writings.

The following are some examples of the number of manuscripts of ancient writers that have survived. The plays of Aeschylus are preserved in perhaps 50 manuscripts, of which none is complete. Sophocles is represented by about 100 manuscripts, of which only 7 have any appreciable independent value. The Greek Anthology has survived in one solitary copy. The same is the case with a considerable part of Tacitus’ Annals. Of the poems of Catullus there are only 3 independent manuscripts. Some of the classical authors, such as Euripides, Cicero, Ovid, and especially Virgil, are better served with the numbers rising into the hundreds.

The numbers of manuscripts of other writers are: for Caesar’s Gallic War 10, Aristotle 49, Plato 7, Herodotus 8, Aristophanes 10. Apart from a few papyrus scraps only 8 manuscripts of Thucydides, considered by many to be one of the most accurate of ancient historians, have survived. Of the 142 books of the Roman History of Livy only 35 survive, represented in about 20 manuscripts. Homer’s Iliad is the best represented of all ancient writings, apart from the New Testament, with something like 700 manuscripts. However, there are many more significant variations in the Iliad manuscripts than there are in those of the New Testament.

When we come to the New Testament, however, we find a very different picture. Altogether we possess about 5,300 partial or complete Greek manuscripts. Early on, the New Testament books were translated into other languages, which seldom happened with other Greek and Latin writers. This means that in addition to Greek, we have something like 8,000 manuscripts in Latin, and an additional 8,000 or so manuscripts in other languages such as Syriac, Armenian, Ethiopic, Coptic, Gothic, Slavic, Sahidic and Georgian. As these translations began to be made before the close of the second century, they provide an excellent source for assessing the text of the New Testament writings from a very early date — Dick Tripp (Anglican Clergyman) Exploring Christianity — The Bible.

Because Jerome was able to work from Greek texts that were already considered ancient in his own day — and that have since been lost — his Latin translation remains of inestimable value to biblical scholars. He also translated the Old Testament from the Greek Septuagint into Latin, as well as making another translation of the Old Testament directly from Hebrew and Aramaic.

September 30, 1452, exactly 1022 years after St. Jerome’s death, the first printed book was published by Johann Guttenberg in Germany. And what text of the Bible did Guttenberg publish? Why the Latin text of Jerome, of course.

The Guttenberg Bible fixed, or stabilized, the text of Scripture much better than hand written copying could do, but even back in the 16th century, it was recognized that critical attention to Jerome’s text was sorely needed. During the intervening millennium, Jerome’s text had been copied and recopied by hand to the point where someone needed to do for it what Jerome himself had done for the Latin texts of his day. But it would not be until the 20th century that an attempt could be made to reconstitute Jerome’s translation according to a critical assessment of the surviving manuscripts.

Once again it was a pope, this time Pius X, who made it his determination to prepare for a critical revision of the Latin Bible. In May 1907, he assemble the abbots of the various Benedictine congregations in Rome and ordered the beginning of the long and arduous task of determining as accurately as possible the text of St. Jerome’s Latin translation, made in the fourth century.

This included decades of patient research through two world wars, locating, examining and photographing all the ancient manuscripts and portions of manuscripts held in libraries, museums and monasteries all over Europe. The work was finally published, beginning with the Latin Psalter in 1969, with other sections released throughout the 1970s, and the entire “Nova Vulgata” or “New Vulgate” in 1979.

St. Jerome, patron of scholars and librarians, must have surely been pleased.

(© 2011 Mary Kochan)