The Death-Haunted Art of Friendship: Part III

For Part I of this series, go here; for Part II, here.

For Part I of this series, go here; for Part II, here.

When I was a little girl, like all little girls, I was interested in naming and categorizing my relationships.

You could be my friend, or you could be my best friend, and those things were totally different. I also had a temporary category for relationships more intense and notable than friendship: You could be my “play sister” or “play daughter.” My intuitions about what separated play family from friends, however close, were surprisingly in-line with the classical philosophy of friendship. A friend, I knew instinctively, is for enjoyment and equality; a play daughter is treated with greater care, but obedience is also expected. That was part of the game. A play sister was like a temporary best friend, an ally, as in Christina Rossetti’s “Goblin Market”:

“For there is no friend like a sister

In calm or stormy weather;

To cheer one on the tedious way,

To fetch one if one goes astray,

To lift one if one totters down,

To strengthen whilst one stands.”

Child’s play often incorporates adult concepts, and will inevitably render these concepts intelligible or absurd. As a little girl, I played with the concept of making kinship: family as something you could make, rather than something you were born into. My friends and I had the experience of being born into familial relationships, no matter how fractured they may have been. None of us was in a position yet to create our own kin—except on the playground, for as long as recess lasted.

Kinship is primarily formed through marriage. There are other possibilities, like adoption, but marriage as the standard is so prevalent that anthropologists and sociologists sometimes call other ways of forging kin bonds, like godparenthood, “fictive kinship.” I would argue that it’s no more fictive than any other kind of kinship; they are all social constructs and they all respond to real human needs. A “play daughter” may be fictive kin, but a goddaughter, in a culture which takes godparenthood and godsiblinghood seriously, is real kin.

In the first installment of this series we saw how friendship often seems to end its social or public life with the death of one of the friends, and how the surviving friend may attempt, through art, to express his grief and combat this sense that the friendship has vanished from view. There is another way in which friendship may resist death, however: Friendship may become a form of kinship. This understanding of friendship has almost been lost in today’s American society, but it is a deeply Christian response to both friendship and death.

What differentiates friendship and kinship? First, the ties of kinship are generally thought to be stronger. Although we now have a phrase, “the chosen family,” meaning the friends and relatives who stand by you when perhaps closer biological kin fail to act with love, in general we do still think and speak as if kin is a more intense and inescapable relationship than friendship. (“Intense” and “inescapable” are obviously not synonyms for “better”!)

Second, kinship tends to have more clearly-delineated roles and obligations. To a certain extent you can write the rules for your own friendships; they aren’t ritualized or standardized, and social expectations tend to be limited and flexible. This causes difficulty for those who do take on painful obligations to their friends, since the broader society of employers and social contacts may not recognize the friendship as a relationship that requires the kind of sacrifices and dedication a marriage or parental relationship would require. But limited and flexible expectations work well for us overall, since nobody wants to have only those friends whom she’s willing to treat as kin.

And finally, while friendship is generally understood as a relationship which links two people together, kinship links families. This is how kinship resists death: It embeds the new kin into one another’s family trees, with roots going down into the past and branches flowering out into the future. Kinship-creation is what’s happening in the song “Sunrise, Sunset” from Fiddler on the Roof, in which the parental generation marvels as their children arrive at the wedding canopy and take their place in the long line of the generations, those past and those yet to come.

Kinship-creation outside of marriage and adoption continues to happen in this country—under the radar. I’ve seen it mostly through my work at a pregnancy center, where we work with many low-income black women. These women speak of their godparents and their “godsisters,” the women with whom they share a godparent. Those relationships, forged at the baptismal font, have major implications for their lives. Godparents often take on parental responsibilities, especially in fragmented families where one or both biological parents are absent. Godchildren seek advice and material help from their godparents, and in return, they give respect and obedience. Godsisters are loving allies, treated much like blood sisters; you have obligations to watch over your godsisters and help them out, both spiritually and materially, whenever you can.

Alan Bray would recognize these relationships. Bray, a historian of medieval England, wrote one of the most beautiful historical studies I’ve ever read: 2003’s The Friend. This book is dryly humorous (in the introduction he says that he’s “returning to its owners” the term “traditional religion”) and well-written, with most chapters ending on a cliffhanger. It’s a thoughtful book, acknowledging the conflicts and problems inherent in the kin relationships he describes. But above all it’s a book of reclamation, rediscovery of forgotten Christian history.

Bray’s book has godsiblings in it as well. (In fact, the English word “gossip” is short for godsibling.) In this case the word refers to the person to whose children you stand as godparent. Standing as godparent for a child bound you not only to that child but to his or her parents: Your families were intertwined. (This kinship placed restrictions on marriage, such that you couldn’t marry your godparent’s biological children. That restriction continues to hold in at least some branches of Orthodox Christianity.) Both godparenthood and godsiblinghood came with ritual, obviously, and with acknowledged obligations.

But Bray’s research found something even more removed from contemporary understandings of kinship—something just as deeply Christian as godsibling obligation, but more thoroughly forgotten. He found that in English “traditional society,” two friends could form, through standardized vows and a ritual often culminating in receiving the Eucharist together, a union with the kind of death-defying bonds and obligations which signal kinship.

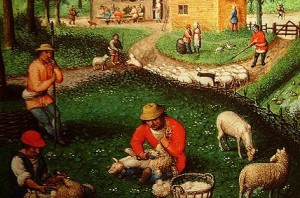

These obligations included the duty to care for your friend’s children after his death. The vows were often taken between married knights, for whom death was an everpresent threat and the care of fatherless children a pressing concern. They might include promises to have Masses said for the friend’s soul if he should predecease you. Friends might even be buried together. The fact that these vows created a form of kinship was reflected in the language used to describe the friends: They were called, among other things, “wedded brothers.”

This language, as Bray makes clear in his conclusion, does not mean that we’re seeing here a “gay marriage” avant la lettre. Many of these men were already married, the Church obviously prohibited sexual relations between men, and at any rate, since brothers certainly can’t marry, the term is clearly being used to indicate a form of kinship as real and deep as both marriage and brotherhood but identical with neither.

Nonetheless, defensiveness about what these vows are not shouldn’t hide from us the beauty of what they are. They are forms of promise-making and family-making which are beautiful in themselves and were, as Bray shows, often accompanied with deep personal devotion. While some of these relationships were probably primarily practical, many of them were truly loving—a situation not unlike the marriages of the time, which were always practical economic necessities but could also be sites for tenderness and love between men and women.

Economic pressures have always shaped our forms of love, at least since we left Eden. Godparent and godsister relationships may persist in inner-city black communities precisely because people in those communities need all the kin they can get. That situation is increasingly everyone’s situation, as the extended or traditional family gives way to the nuclear family and then the postnuclear family. It may be time to rediscover these Christian forms of kinship-creation, to found our friendships in the Eucharist.

We might even be able to learn from the past. Bray’s book draws out the possibilities for conflict between loyalty to one’s friend and his children versus loyalty to one’s wife and one’s own biological family. The possibility of conflict occurs whenever we have more than one form of love or loyalty; but we might be able to mitigate that conflict by including in a renewed form of vowed friendship some explicit acknowledgment that the friends will support one another’s other loves and kinship obligations, including marriage. This would acknowledge both contemporary marriage’s greater need for social support, and the fact that the friends are linking not merely their present lives but their futures.

Most of us are not artists. If we want our friendships to have social reality beyond our deaths, they must in some way become a part of our family story, our family tree. Both “god-family” relationships and vowed friendships offer possibilities—radical, and radically Christian, forms of love.