America and Ancient Rome: Comparisons

History offers insightful comparisons and contrasts between past and present. A generation or so before the birth of Christ, Rome lost her republic to political and cultural decadence. Although reformers emerged in the political and literary spheres, their efforts failed and ancient democracy faded into oblivion. Whereas in America, the game is not quite up.

Although the republic of Rome ceased to exist, imperial Rome endured for centuries. Transmutating into a durable Principate, it continued to showcase a few trappings of democracy. In reality, however, it had become an autocracy headed by warlords styled Caesars or Augusti or Emperors. Thereafter, its appeal to the patriotic sentiments of citizens was based not on liberty, nor on rule by the Senatus Populusque Romanus (SPQR), but rather on bread, circuses, and military conquests.

Likewise, the United States continues to tout the trappings of democracy. We hold contested elections, and bow patriotically to what President Gerald Ford proclaimed when Richard Nixon resigned.

Our Constitution works. Our great republic is a government of laws and not of men. Here the people rule. [Swearing-in address, 8/9/1974]

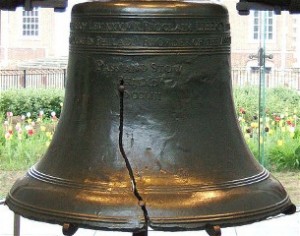

To what extent Ford spoke the truth in the wake of the Watergate scandal is debatable. Today his words clang like a cracked bell. Rampant legislation from the bench, where sits an unelected, life-tenured oligarchy bedecked in black robes, hardly resonates with the rule of law.

Neither do plutocratic protection plans for incumbent politicians accord with “government of the people, by the people, and for the people.” Abraham Lincoln won his single term in Congress during an era when rotation in office was a “‘long cherished'” principle[1]. Nineteenth century Americans would have been aghast at reelection rates enjoyed by today’s Congressmen, as high as 99% in some years. Moreover, Lincoln was elected in a campaign costing so little that after his election in 1846 he returned most of his $200 war chest. Maybe old Abe’s vaunted wit would have found something ironically humorous about today’s multi-billion dollar Federal election cycles.

Roman propagandists boasted pridefully about the process of electing magistrates. But during the dying days of the republic, Julius Caesar rose in the ranks by bribing the electorate; and eventually he managed to make himself dictator. Which is not to say that Caesar weakened Rome militarily; quite the opposite. Under his sway the size of the Empire expanded even as republican institutions shriveled.

Much the same process is at work in America. Democracy atrophies, emptying the republican framework cherished by Americans since the days of George Washington. But the shell that remains may continue on for generations, or even centuries. How much longer, however, will citizens fall for the proposition that democracy consists in crowning winners in brawls between two big political machines?

Viewed from the perspective of real democracy within the framework of a genuine republic; what good is the continuation of a electoral process masquerading as rule by the people, when in reality it is run by the few and the very few? With attenuated powers the Roman senate staggered on until AD 603, but as a sort of debating society, much like today’s British House of Lords. Democracy is rule by the people, not merely the right of the people to debate and dissent.

As in pagan Rome, our children and grandchildren may prove willing to uphold the parody of a republic – one which boasts a military prowess straddling continents; an economic capability of feeding its citizens via welfare, and of keeping them on wheels; and a culture entertaining the people with hedonistic diversions. Under such a scenario, “We the People,” the first three words in the Constitution, will be as dead as Roman democracy when Petronius wrote his Satyricon.

About the same time the Stoic philosopher, Seneca, was murdered by order of the Emperor, Nero – “when Sadism sat on a throne brazen in the broad daylight.” Seneca’s last years were saddened by witnessing the loss of liberty and the downfall of the republic. Throughout his life he carried republican values which he had imbibed in school not long after his birth in Cordoba, Spain.[2] Disillusionment, strong enough to overwhelm even Seneca’s Stocism, was described by a 20th century Spaniard, Jose Ortega y Gasset. “’I say that the end of a civilization is the scene most imbued with melancholy for men. The possibility that a civilization should die doubles our own mortality.’”[3] Or triples it when a man has to raise a family in such a morbid environment.

In Roman culture one could find refuge from melancholy, most notably in the rise of Christianity as preached by men of conviction and intellect. In America, by contrast, religious truth is not gaining but declining in social influence. We are witnessing, as the Venerable Fulton J. Sheen said in Boston, 1974, not the demise of Christianity but the death of Christendom. Resurgent paganism would confine us to a sort of cultural arctic circle, with our Judeo-Christian heritage hanging like an ice cycle on an Eskimo lodge.

For Americans, therefore, the long-term looks even more chilling than for Roman citizens anticipating the future. Christians like the 3rd century writer, Commodian, loathed the Roman Empire, and his verses anticipate its breakup like a balmy breeze.[4]

The death of someone despised brings the temptation to be joyful. Whereas the impending death of a loved one provides occasion for sorrow. Hence as Americans who generally cherish our country – or at least its noble past – we suffer a grief proportionate to our patriotism.

Christians in this nation would love to have seen the ignobility of popular culture quashed, and high ethical standards restored to preeminence. Instead Federal judges worked fiendishly to secularize the public square, thus letting diabolical fires conflagrate society. It has been agonizing to witness, especially for citizens old enough to remember what times were like before cultural arsonists went to work on America. While Christ’s agony in the garden was immeasurably more intense, ours has been more protracted.

Evidently the Supreme Court never learned, or else forgot, what the Irish lass said long ago: “I realize that for nations, as for individuals, true greatness lies in goodness.” (Eveleen Nicholls, c. 1909)

And so to think about our country’s future is more distressing for us than for Commodian. He looked on hopefully, as if to a dawn, whenever Germanic invaders crossed imperial frontiers. But he foresaw the future through a glass darkly.

As it transpired, the Constantinian revolution gave the Empire a spiritual shot in the arm. Reinvigorated as a Christian empire, it lasted another 1½ centuries in the West, and more than a millennium in the East. And yet it wore a cancer at the heart of its cultural heritage.

According to G.K. Chesterton, Western Europe’s long-term hope was not in improving imperial trends (as in Constantinople and the eastern Empire), but rather in a thoroughgoing “purgation” or “emancipation” from pagan manners and morals. The only remedy strong enough was the era of the Dark Ages. The Gothic invasions bequeathed an era of collective mortification in which heathen culture was purged and society emancipated from the obsession with sex, particularly the unnatural proclivities ingrained into Greco-Roman society. (Chesterton, St. Francis of Assisi, chapter 2).

Accordingly, 3rd century Romans like Commodian might have eschewed the Christian revolution under Constantine, preferring instead what Chesterton described as “the long penitential period.” Chesterton saw many generations of cultural mortification as requisite to “the twilight of morning,” i.e. The 13th, Greatest of Centuries.[5]

I’m not sure whether to rejoice or lament the fact that no comparable opportunity for “expiation” is yet on the horizon for pagan America. But times change, and now with increasing rapidity. My children or grandchildren may live to endure it, though I out-die it.

Another grim contrast between Rome and postmodern America is that a clear-eyed perspective on our country’s situation is obscured by starry-eyed super-patriots. As a case in point, a national talk show host of some prominence brags on every program about “the greatest nation on God’s green earth.” But like clear-eyed Romans, more level-headed patriots exhibit tough love of America while eschewing triumphalism.

In Rome, moreover, pagan progressives such as Ovid, who admired decadence and despised the rusticitas of his ancestors,[6] began losing influence compared to the surge of brilliant Christian apologists and intellectuals from St. Justin Martyr through St. Augustine. In America, by contrast, decadence and its advocates are waxing strong, with no indications of a waning cycle.

On the optimistic side, however, the United States is exceptional – as, to a lesser extent, was Rome. And our institutional advantages, including Article V of the Constitution, could come to the fore if “We the People” ever mobilize for the purpose of turning things around. Counterrevolutions are not impossible, notwithstanding the proverbial allegation that you can’t turn back the clock. America’s lofty heritage portends that someday our fellow countrymen might strive for a restoration, calling the USA back to the golden principles from which it sprang.

Returning to original principles is a well precedented path to reform, pursued by reformers as far back as ancient Sumer, the earliest civilization.[7] Pope Leo XIII wrote in 1891 that “when a society is perishing, the true advice to give to those who would restore it is to recall it to the principles from which it sprang.”[8]

But calling Rome back to her pagan roots was a foolish strategy for Diocletian, Galerius, and other imperial persecutors. Their reforms were abject failures for three reasons. First, the Greco-Roman pantheon which they proposed to revive was spiritually degrading. Second, their agenda for restoration included resisting the best thing Rome had going, the upsurge of Christianity. Third, in the words of Gamaliel, “if it is of God, you will not be able to overthrow it. Else perhaps you may find yourselves fighting even against God.” (Acts 5:39)

Restoration would seem, however, to be a sure winner if it is ever attempted in America; with our legacy of a wise Constitution in tandem with religion and morality. In China, by contrast, or South Africa, there would be no good purpose in restoring the Manchu or apartheid regimes. Iniquitous historical roots are unworthy of restoration.

How can bad grapes yield good burgundy?

Or rancid soil rhododendrons and roses?

For the same reason the restorative strategy was no option at all for the Christian revolution of the 4th century. And so Constantine, or rather his successors, took another well-heeled approach as articulated by the Roman historian, Sallust, a contemporary and partisan of Julius Caesar. Sallust advised Caesar that internal or domestic discord could alone destroy the empire. Therefore,

‘We must consolidate the benefits of concord

and destroy the evils of discord.’[9]

The Christian revolution under Constantine and his successors took more or less the same approach in a culture war conducted over several decades. This kulturkampf culminated in the theocracy of Theodosius the Great (379-395) and his final outlawing of paganism, thus securing imperial unity on the basis of the new religion.

The principle of theocratic unity continued to prevail in the Eastern Roman Empire, the Byzantine Empire, for many centuries. Meanwhile, after the collapse of the Roman Empire in the West, AD 476, fragmentation was somewhat mitigated by the unifying effect of the Papacy, and by the common denominator of Roman Catholicism throughout Western Europe.

In conclusion, the history of the Roman republic is similar to that of the “Great Republic” (as Winston Churchill called it when I was a boy). Just as Rome took the low road into political and cultural decadence, so the USA is well down the same slope. The Roman Republic never returned, although the Roman Empire remained strong for centuries.

Similarly, America’s status seems secure – at least for the time being – as the world’s sole military superpower. Whereas, alas, the future of America’s republican form of government is very much in doubt. No longer are citizens called in domestic matters to “keep it,” as Ben Franklin said of the Republic in 1787, but rather to recover it by restoring the scepter to the written Constitution and by getting back to God.

On the spiritual plane, the more apt historical comparison is the Roman Principate versus postmodern America. In juxtaposing the two great empires, each home front reveals polarization between paganism and Christianity. The Christians were on the winning side in the 4th century. In the United States the culture war has been going the other way, over the half-century since the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

Prior to Constantine, before the contest was decided in favor of Christianity, some in the Church looked hopefully to Christ’s return in glory; and others, more mundanely, to the Gothic invasions to end the Empire. Today too we hear otherworldly comments like, “we’ve read the Book, we know who wins in the end.” Or dire political forecasts like “the future belongs to China.”

How it goes for America in the next two or three generations will depend largely on whether faith, fervor and valor shall reappear, as exhibited by activists during the “Christian Revolution Under Constantine.”

[1] Robert Struble, Jr., “House Turnover and the Principle of Rotation,” Political Science Quarterly 94 (Winter 1979-80): 649-667.

[2] Quotation on Nero from, G.K. Cherterton, St. Francis of Assisi (New York: Image/Doubleday, 1990), chapter 2, “The World St. Francis Found,” p. 29 — originally published 1924. On Seneca: Santo Mazzarino, The End of the Ancient World, (NY: Alfred A Knopf, 1966), p. 33.

[3] Ortega quoted by Mazzarino, ibid., pp. 170-71.

[4] Mazzarino, ibid, pp. 44, 46. Commodian flourished c. 250, A.D. and wrote poetry in Latin. I’m reminded of the colonial American poet, Michael Wigglesworth, and his Day of Doom.

[5] Chesterton, supra, pp. 25-26, 31-33, 36.

[6] Mazzarino, supra, p. 32, citing Ovid, Ars Amatoria, 3.121 ff.

[7] Mazzarino, p. 31, cf. 27.

[8] Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum 41 (1891). Similarly, the Washington State Constitution, Declaration of Rights, sect. 32, states: “A frequent recurrence to fundamental principles is essential to the security of individual right and the perpetuity of free government.” Would that the people of my home state might take their own Constitution to heart.

[9] Mazzarino, supra, p. 27, cf. 31.

____

See also my, “Constantine and Christendom: Glory or Calamity?”

And the four part series for the 17th centennial, “Christian Revolution Under Constantine“