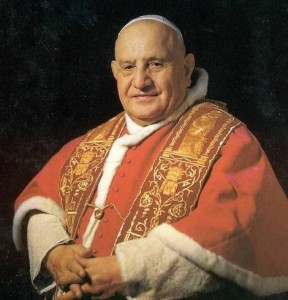

John XXIII: Saint in the Age of Television

In 1958, a congenial old man, Angelo Roncalli, was elected to the chair of Peter. He was to be a caretaker pope, someone to keep the ship steady while the cardinals identified a more long-term leader. That smiling old man soon stunned the world by calling the first ecumenical council in nearly a hundred years. That was not exactly what the Cardinals had in mind.

In 1958, a congenial old man, Angelo Roncalli, was elected to the chair of Peter. He was to be a caretaker pope, someone to keep the ship steady while the cardinals identified a more long-term leader. That smiling old man soon stunned the world by calling the first ecumenical council in nearly a hundred years. That was not exactly what the Cardinals had in mind.

But they had chosen a profoundly holy man for the job, someone who’d be declared “Blessed” just a few decades later. One thing about holy people — they are docile to the Holy Spirit. The Spirit blows where he wills, and they follow without hesitation. Don’t choose that sort of person to man the helm if you don’t want to rock the boat.

Docility requires humility, which is a critical component of holiness in any age. When asked to enumerate the four Cardinal Virtues, St. Bernard of Clairveaux (11th century) replied “humility, humility, humility and humility.” If there was a salient characteristic of Angelo Roncalli, it was these four cardinal virtues!

Born to a peasant sharecropping family of Northern Italy, Angelo never lost touch with his roots. As a seminarian, he spent his summers working the fields with his brothers. Whenever he removed the white gloves of papal ceremonial, one could see the calloused hands of a peasant.

Pope John XXIII was the first pontiff to allow representatives of atheistic communist governments to visit the Vatican. On one occasion he received a Soviet Diplomat and his wife in private audience. He handed the wife a gift, a beautiful rosary. When he placed the beads in her hand, she exclaimed to her husband in Russian, “Look, he has the hands of a worker; he is one of us!” Of course she did not expect this peasant-pope to understand. But she was wrong! This peasant spoke not only Latin and his native Italian, but also French, Greek, Bulgarian, Turkish, and Russian. Duty required that he learn them. Duty had also required that he become an expert in the Fathers of the Church and the Reformation, so he got his doctorate in Church history. A highly cultured peasant indeed!

Yet the comment of the Russian woman gave him great satisfaction — he was pleased to be recognized as a peasant, a worker, as “one of us.”

That highlights another quality of John’s holiness that is a model for us all. No one left his presence without feeling that they had something profoundly in common with him, that he was with them, for them. All, even atheists, felt somehow affirmed by him.

This is not to say that he was without principles. At outset of the council, he strongly affirmed that the essence of Catholic doctrine and morals would not change to suit modern tastes. He had strong convictions about modesty in dress, and he frequently reminded those who forgot. In his opening speech, he included strong criticism of those “prophets of doom” who saw nothing but sin and danger in the modern age.

Yet he was always able to distinguish persons from their actions or ideas, and recognize the human dignity of everyone. His affirming smile let people know that he found something delightful in them, the goodness of God that could not be obscured by their sins or politics. He was always able quickly to find some common ground and build rapport.

He was not liberal or conservative. He was just Angelo Roncalli, disciple and priest of Jesus Christ. The conservatives loved him because of his traditional piety. The liberals claimed him because he was open to change.

Yet there was not a political bone in his body. He was not trying to be “diplomatic.” He was just transparently himself. Always. This is why he was chosen to serve in the Vatican diplomatic core for so many years. Because of his authenticity and integrity, everyone trusted him. He succeeded where others failed, building bridges, reconciling foes, defusing crises. Few know that when the Cuban missile crisis brought the world to the brink of nuclear war, it was Pope John who helped Kennedy and Khrushchev come to a peaceful resolution.

Pope John’s ability to get erstwhile enemies talking was part of why the Holy Spirit was able to use him to make Vatican II happen. He made progressives and traditionalists sit down at the same table and work together. When some wished to submit their resignations, he refused with a smile and told them it was their duty to listen to each other and collaborate for the glory of God.

Saint that he was, he took God’s work and God’s glory very seriously. Yet his holiness prevented him from taking himself, and his glory, too seriously. He had the proverbial “Roman nose,” big ears and a waistline reflecting his love of pasta. When he was given a glimpse of himself for the first time in a full length mirror, dressed in full papal regalia, his secretary overheard him mutter under his breath with a smile, “My God, this Pope is going to be a disaster on television!”