Book Review: My Peace I Give You: Healing Sexual Wounds with the Help of the Saints

In early 2012, the Pontifical University in Rome held one of its most important conferences ever. “Towards Healing and Renewal” was an international symposium, sponsored by the Vatican , devoted to the terrible abuse crisis in the Church. What made the event so extraordinary is that is was opened, not by a high-ranking prelate but by an ordinary lay woman, Marie Collins, who came to speak as a victim.

In early 2012, the Pontifical University in Rome held one of its most important conferences ever. “Towards Healing and Renewal” was an international symposium, sponsored by the Vatican , devoted to the terrible abuse crisis in the Church. What made the event so extraordinary is that is was opened, not by a high-ranking prelate but by an ordinary lay woman, Marie Collins, who came to speak as a victim.

Her presentation was eloquent and heartbreaking, and had a powerful effect on all those present. Equally important, however, were the remarks she made to the press afterwards. Having spoken of her suffering, and the pain experienced by so many others, she raised an issue that has been virtually absent during this whole crisis. Why, she asked plaintively, has there been such “a lack of pastoral care directed toward victims?”

“In my experience,” she added, “there’s been very little spiritual help given to survivors.”

Collins, who bears only good will toward the Church, was trying to help. She was pointing the Catholic hierarchy in the right direction, highlighting their greatest weakness in response to sexual abuse within the Church. There have been reckonings with justice for the perpetrators; expressions of shame and remorse from Catholic leaders; financial settlements; and vigorous procedures put in place to protect the innocent—all of which is necessary and welcome (and long overdue). But what has been lacking, from the very outset, is a vigorous pastoral and spiritual outreach to the victims.

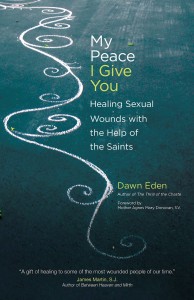

Given this void, a remarkable new book has appeared, and could not have arrived sooner: Dawn Eden’s My Peace I Give You: Healing Sexual Wounds with the Help of the Saints. It is not, it should be emphasized, a response to the clergy-abuse crisis as such, or specifically directed toward clergy-abuse victims, though the author certainly hopes they will benefit from it. Eden ’s book is intended for a much wider audience—since the overwhelming majority of abuse is not committed by clergy. She provides exactly what Collins requested: a guide for the spiritual needs of the victims, based upon the promises of Our Lord, the sacraments, and the intercessory power of the saints.

Eden is a well-known writer and speaker with a unique background. A former rock journalist, immersed in freewheeling ways, she underwent an astonishing conversion to Evangelical Christianity at the age of 31. As she grew in her faith, she eventually entered the Catholic Church, embracing the fullness of Christian revelation, and is now actually pursuing a doctorate in spiritual theology. Her first book, The Thrill of the Chaste: Finding Fulfillment While Keeping Your Clothes On (2006), was written during her transition period, and defends Christian morality against our promiscuous “hook-up” culture. It’s received enormous praise, sold over 20,000 copies (in English, Spanish, Polish and Chinese), and won Dawn speaking engagements all over the world.

But even with this acclaim, Eden has been carrying a heavy burden for many years, one never openly dealt with until now. For the first time, Dawn reveals that she was a victim of sexual abuse herself.

My Peace I Give You is her moving story of how she confronted and ultimately overcame that abuse. But it is also, on a broader level, a recovery manual for anyone who has lived through such trauma. It is a unique and ground-breaking work, sure to prove invaluable to victims, their families, spiritual counselors and religious leaders.

Eden’s book breaks new ground, for the world is not used to hearing Catholics talk about sexual abuse other than clergy-abuse, or challenge our secular culture which, along with mistaken religious ideas, encourages silence and misplaced shame. Further, My Peace is not limited to physical abuse, but covers many other forms as well: verbal, mental and emotional.

The book opens with Eden ’s description of her own multiple victimizations (by secular men, not clergy), which occurred during her childhood. She is sensitive and discreet in conveying them, knowing how flashbacks can be triggered by too much information. The gravity of what was done to her, however, comes through with searing force. “I felt like there was a black mark on my childhood,” she writes, “a blotch of indelible ink. The more I tried to cover up this feeling by repressing the bad memories, the more the pain, loss, and shame threatened to seep into every corner of my adult life.”

Therapy helped Dawn understand how her childhood related to her later, self-created persona of a counter-cultural rebel: “The false self I inhabited during my teens and young adulthood, the sexually aggressive rebel, stemmed from dissociation, a psychological defense mechanism common in trauma victims. My dissociation started with the erroneous belief that I was responsible for my abuse. Feeling responsible, I felt tainted. Feeling tainted, I felt inferior. Feeling inferior, I wanted to regain a sense of control over my life.”

Full control would not arrive for many years; and even after her conversion, it seemed elusive. What Dawn finally realized is that it couldn’t be obtained on her own, even as a committed Christian, but only by uniting her sufferings with those of Christ, as have countless saints. She takes the latter as her guide toward healing from abuse, and does so in a way that humanizes them without diminishing their heroic sanctity.

My Peace I Give You is intricately structured and connected by the overarching theme of God’s love, and its many dimensions. In eight chapters, Eden describes the lives of canonized saints and saints in waiting—well-known ones like St. Thomas, St. Therese of Lisieux and Dorothy Day, and lesser known Blesseds like Laura Vicuna and Karoline Kozka–revealing how and why each one offers hope for abuse victims today. By doing so, she breaks through the artificial barriers often placed between us and these mighty representatives of God.

We tend to think of saints as super-human and other-worldly, but this, as Eden shows, makes them almost unapproachable on a truly personal level. The reality is that the saints were just as human as any of us, and some of them suffered unspeakable abuse, though this is rarely mentioned today. When it is, it is usually quickly and superficially passed over.

A classic example is G. K. Chesterton’s biography of St. Thomas Aquinas, which philosopher Etienne Gilson called the best of its kind. For the most part it is, but even so great a mind as Chesterton was unable to grasp the depth of the abuse St. Thomas Aquinas suffered from his own family. Describing how his mother and brothers kidnapped and jailed Thomas– then sent him a prostitute, to try to prevent him from becoming a Dominican—Chesterton comments:

He accepted the imprisonment itself with his customary composure, and probably did not mind very much whether he was left to philosophize in a dungeon or in a cell. Indeed, there is something in the way the whole tale is told, which suggests that through a great part of that strange abduction, he had been carried about like a lumbering stone statue. (emphasis added)

Chesterton doesn’t even consider what this familial abuse may have inflicted on Thomas, but instead treats it as an almost comical adventure, merely asking what the prostitute whom St. Thomas chased away with a fiery stick, “must have thought of that madman of monstrous stature juggling with flames and apparently threatening to burn down the house.”

Of course, the great saint was harmless—he simply wanted the would-be seductress out of his room—and Chesterton quickly admits as much. But his failure to explore the trauma Thomas underwent, and instead merely write how the saint returned to “ that seat of sedentary scholarship, that chair of philosophy, that secret throne of contemplation, from which he never rose again”—as if the abuse never left a mark on him –is striking.

Eden ’s account of St. Thomas is far more convincing. Basing herself on the best biographical sources, she shows that, far from being a “lumbering stone statue,” Thomas was aware and acutely responsive to the abuse he suffered, and as such is a saint anyone who has been similarly harmed by their family can invoke. What his family did to Thomas, Dawn underscores, “wasn’t simply a temptation. It was a violation.”

By taking St. Thomas out of his “scholarly” Summa Theologica mode, and offering him up as an ideal intercessor for victims of abuse, Eden is directly challenging those who would confine St. Thomas to an academic pedestal, where the graces he can offer, through the will of God, would be limited. Ironically, those who would imprison Thomas like this are—at least on a spiritual level– trying to prevent him from fulfilling his full potential, just as his misguided family was.

As she moves onto more contemporary saints and Blesseds, Eden offers equally fascinating and challenging portraits. A key point she makes, in her discussion of St. Maria Goretti, for example, is that many devout Catholics believe she is a saint because she fought her persecutor and was able to avoid rape. In fact, she is a saint, because she was holy and resisted her assailant. But even if she had been raped, Dawn stresses, she would have been equally saintly. This has always been Church teaching, even when it’s been misunderstood or forgotten. Writing about the early virgin martyrs, St. Augustine, notes Eden, “lashed out at pagans who claimed that virgins who had been raped were no longer virgins,” asking what sane person can suppose that, if a body be seized and forcibly made use of to satisfy the lust of another, the victim thereby loses his or her purity? This is of huge importance to victims of rape, and others who’ve been sexually abused; for some tragically believe that once physically assaulted, they can never be “pure” again. Even Catholic victims who sought the Church’s aid, but who had been never told this, were haunted by the idea. In the words of Marie Collins, before she understood her complete innocence: “I did not turn against my religion, I turned against myself.”

But the idea that a victim of sexual abuse is not as holy or chaste as someone who is able to escape physical violation—as if the Church rewards spiritual points for those who are quicker or stronger, fending off their attacker—is wholly against any Catholic understanding of sanctity, and Eden makes the point well. “The race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong” (Ecclesiastes 9:11), and sainthood is not an athletic competition, but a measurement of our love of God, and moral goodness.

As original and creative as her work is, Eden ’s book is in perfect harmony with Catholic Tradition. If there is a theology behind it, it is the “theology of suffering,” symbolized by the Passion of Christ, and practiced by the saints. It is a theology our last two popes have developed and enhanced, against the trivialization of Christian spirituality, rooted in the Cross of Our Savior. As Dawn writes:

Christians believe the Cross is, in the phrase of an ancient hymn, spes unica, our only hope. Christ, through suffering in his human nature, took upon himself all human suffering. He invites us to be joined with him in baptism because, in the words of Blessed John Paul II, he ‘wishes to be united with every individual, and in a special way is united with those who suffer. (Salvifici Doloris, 24).

Pope Benedict elevates the same teaching:

The Christian faith has shown us that truth, justice and love are not simply ideals, but enormously weighty realities. It has shown us that God—Truth and Love in person—desired to suffer for us and with us. Bernard of Clairvaux coined the marvelous expression: Impassibilus est Deus, sed non incompassibilisi—God cannot suffer, but he can suffer with. Man is worth so much to God that he himself became man in order to suffer with man in a utterly real way—in flesh and blood-as it is revealed to us in the account of Jesus’s Passion. Hence, in all human suffering, we are joined by one who experiences and carries that suffering with us; hence, con-solatio is present in all suffering, the consolation of God’s compassionate love—and so the star of hope rises. (Spe Salvi, 39).

Perhaps the most moving part of this book is where Dawn reveals how she finally experienced that hope, before the Blessed Sacrament, after a veil of tears– comparing her recovery to the healings of Blessed Laura Vicuna and St. Josephine Bakhita, two models of heroic sanctity who forgave their abusers, having suffered immensely, but having been transformed by God’s healing light.

The message of Eden ’s beautiful and inspiring book is that these special friends in Heaven, like all of God’s other triumphant saints, are now waiting to intercede for any of us, should we, too, need an all-encompassing healing.

“That, I realize, is what the saints have done for me,” Dawn writes. “They opened their hearts to me so that I might, through their love, enter more deeply into the Heart of Christ. It is the mission of the entire Communion of Saints—that we may all be one, even as the Father and the Son are one (John 17:11). In His will is our peace.”

Reprinted, with permission, from the April 2012 issue of Inside the Vatican magazine. (www.insidethevatican.com).