A Crime in Time—and Again

Anne Roback Morse also contributed to this article.

California has a long-history of eugenics, and it is easy to condemn the eugenics laws that the Golden State passed in 1909 and implemented until 1952. These sterilizations were visited upon “the unfit” in mental hospitals, upon the uneducated, and upon non-white minorities in disproportionately high numbers. Who would now condone the coercive and forcible sterilization—with state approval—of over 20,000 men and women?

California has a long-history of eugenics, and it is easy to condemn the eugenics laws that the Golden State passed in 1909 and implemented until 1952. These sterilizations were visited upon “the unfit” in mental hospitals, upon the uneducated, and upon non-white minorities in disproportionately high numbers. Who would now condone the coercive and forcible sterilization—with state approval—of over 20,000 men and women?

Yet despite the unanimous modern condemnation, non-consensual sterilization of those deemed “unfit” for the benefit of “the common good” continues to occur. A closer look at how such an evil came to be permitted in the past can perhaps help to explain why such eugenic crimes continue to exist in the present day.

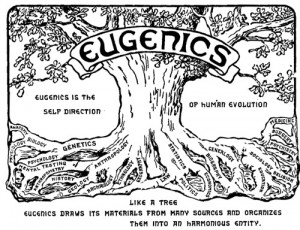

By the late 1800’s, eugenics had become something of a fashion among the wealthy and the educated. Darwinian evolution and Mendelian genetics fermented in the minds of the elite, suggesting to them that Man should take control of his evolution and actively eliminate deleterious genes from the population by preventing their bearers from breeding. Such thoughts were not to remain merely stimulating thought experiments for long. In those days before the full horror of efficiently implemented eugenic programs was made evident, and racism was still socially acceptable among the upper echelons of American society, there was nothing to stop to elite from acting against their perceived inferiors.

Eugenics entered the mainstream with scientists, educators, and philanthropists all jumping on board. The first president of Stanford University was chairman of the American Eugenics Commission and the vice-president of the American Society for Social Hygiene. After making a fortune in citrus fruits, Ezra Gosney founded the “Human Betterment Foundation” in Pasadena and authored a book with the inviting title, “Sterilization for Human Betterment.” He was joined at the Foundation by none other than the creator of the IQ test, a Nobel-Prize-winning physicist, and other equally illustrious individuals, all of whom had nothing but disdain for those less gifted than themselves.

By 1909, the movement was politically powerful enough to have their views written into law. The California State Assembly voted unanimously to “permit asexualization [sterilization] of inmates of the state hospitals and California Home for the Care and Training of the Feeble-Minded Children and of convicts in the state prisons.” The bill sailed through the California State Senate as well, with only one senator voting against it.

California’s sterilization laws “permitted” and “provided for” non-voluntary sterilizations, but did not mandate them. That is to say, the decision to sterilize a patient was up to the doctor or medical superintendent of the facility where the patient was being held. A doctor could not be prosecuted for forcibly sterilizing someone, nor for not sterilizing someone. The wide latitude given to medical staff in these matters allowed them free rein to implement their own personal eugenic ideologies.

At Agnews State Hospital, located near San Jose, women were mainly sterilized for “therapeutic reasons.” That is to say, the superintendent was wont to sterilize women when he thought that their having children would be bad for their mental health, not for fear that genetically transmitted disorders would be passed along to their children.

The medical superintendent in Mendocino sterilized women for both “therapeutic” and eugenic reasons. This approach, reflecting both a distorted desire to help the patient and a desire to improve the gene pool, was common during the period of forced sterilizations in California. In describing his motivation in one case, the superintendent began by noting that “she threatened to do harm to herself and to her infant child; that her mental symptoms began at the time of the birth of her child.” His report finished with a eugenic prescription: “[We] believe this patient is afflicted with a mental disease which may have been inherited and is likely to become transmitted to descendants. … we would like instructions to perform the operation of sterilization.”

Other doctors, however, were motivated by pure eugenic disdain for their charges, and evidenced little concern for their well-being. The superintendent of the Stockton State Hospital wrote a letter in 1916 to the State Commission in Lunacy illustrating his purely eugenic motivation:

“If the insane who are capable of reproducing are not sterilized before leaving the hospital, it naturally follows that we will have an ever-increasing, endless chain of insane and defective wards to care for. I made the rather broad statement that California was leading the world in this very important procedure…from statistics which I have been able to gather, I feel that we, in this state, are doing more of this work than is being done elsewhere. I would like to see the law made broader whereby those addicted to the use of alcohol or drugs could be sterilized.”

So it was that medical professionals, motivated by a strange mix of self-superiority and concern for their patients, violated the bodily integrity of those same patients. Yet we cannot say that this dark page in U.S. history has been turned.

For is there not a modern-day equivalent to last century’s eugenics programs in the advocation of generous funding, at both the federal and state levels, for free abortions, contraceptives, and sterilizations for the poor?

To judge by the way that the government pushes contraception, sterilization, and abortion on the poor on the presumption that “they can’t handle children” or “they would be better off without them”, it would appear we still have a long way to go.

Bibliography

“California Eugenics.” Eugenics: Compulsory Sterilization in 50 American States. N.p., n.d. Web. 11 Sept. 2013. <http://www.uvm.edu/~lkaelber/eugenics/CA/CA.html>.

Ingram, Carl. “State issues apology for policy of sterilization.” Los Angeles Times (2003).

Laughlin, Harry H. Eugenical Sterilization in the United States. Chicago: Psychopathic Laboratory of the Municipal Court of Chicago, 1922. Print.

Stern, Alexandra Minna. “Sterilized in the name of public health: race, immigration, and reproductive control in modern California.” American Journal of Public Health 95.7 (2005): 1128-1138.

Wellerstein, Alex. “States of eugenics: institutions and practices in compulsory sterilization in California.” Reframing rights: bioconstitutionalism in the genetic age. MIT Press, Cambridge (2011): 29-58.