Exploitation: Legal Protections for Human Embryos Eroding in France

The cold weather in recent months seems to have brought a flurry of news stories about embryos. In October the 2010 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to the inventor of in vitro fertilization. In November the journal Human Reproduction published a study in which researchers at the University of Barcelona implanted silicon devices in mice embryos to serve as “barcodes”; the Catalonian Ministry of Health has authorized experiments to duplicate the technique with human embryos.

The cold weather in recent months seems to have brought a flurry of news stories about embryos. In October the 2010 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to the inventor of in vitro fertilization. In November the journal Human Reproduction published a study in which researchers at the University of Barcelona implanted silicon devices in mice embryos to serve as “barcodes”; the Catalonian Ministry of Health has authorized experiments to duplicate the technique with human embryos.

On December 1 the special parliamentary commission in charge of examining the draft revision to the French bioethics law devoted the first of a series of round-table discussions to the topic of research on human embryos. Later that month the results of parallel studies of in vitro fertilization in Britain and Sweden were reported, clearly indicating that a woman has a much greater chance of carrying a pregnancy full term if only one embryo is implanted, as opposed to two, although there is still a large risk of premature birth or a low-weight baby.

Finally, on January 12, 2011, hearings were held in an appeal to the Court of Justice of the European Communities to debate the definition of “human embryo” and to determine whether a procedure for deriving nerve cells from embryonic stem cells can be patented under EU regulations.

Significantly, neither the embryos themselves nor their mothers or fathers figure as individuals in any of these stories. They are all about the scientists, except for the news item from France about national legislators. Several clauses of the French bioethics law in its current form, and many of the proposed revisions are highly controversial and have been debated extensively in the secular and religious press. Commentator Pierre-Olivier Arduin is alarmed by what he sees as a forced march to a political arrangement that will perpetuate research on human embryos and human embryonic stem cells.

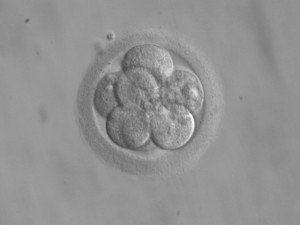

Such research was forbidden by the initial bioethics legislation passed in France in 1994 and by the first revision to the law in 1999. The 2004 revision, however, allowed for “derogations” (authorized exceptions) during a five-year period, provided that the proposed research on embryos and embryonic stem cells [ESCs] offered the prospect of “major therapeutic advances” that could not be pursued as effectively by alternative methods. The 2004 bioethics law was extended for one year to 2010 along with this “moratorium”.

The draft bill being discussed as of this writing in late January would further dilute the original prohibition against research on microscopic human subjects in two ways: it would extend indefinitely the period in which government-approved exceptions would be allowed, and instead of a “therapeutic purpose”, it would require only a “medical purpose”. This would open the door to wider fundamental research in the fields of embryology, genetics and biochemistry and also permit pharmaceutical research, for instance the use of human embryos or ESCs for molecular screening and drug testing.

Ms. Aude Mirkovic, an assistant professor of law at the University of Evry, remarked that it is surprising that the French government should persist in using human embryos in research, now that the European Union, in a directive dated September 22, 2010, has called for an end to “procedures performed on living animals (including fetal and embryonic forms) for scientific and educational purposes”.

In its paradoxical “Opinion #112” concerning “research on human embryonic stem cells and human embryos in vitro”, issued on December 1, 2010, the French national bioethics committee (Comité consultatif national d’éthique, CCNE) dodged the question of the ontological status of the embryo, calling it “an enigma”. It went on to note that current law severely restricts research on the human embryo yet allows the large-scale destruction of embryos in vitro during pre-implantation diagnosis or when the parents no longer wish to have them cryopreserved. According to the tortuous reasoning in the CCNE opinion, only the destruction of embryos is ethically objectionable. “In no case does the possibility of research influence the decision to destroy the embryo. You don’t protect a human embryo from destruction by forbidding research.” Therefore the CCNE suggests two sets of regulations on embryo research: one that conditionally permits experimentation on “spare” frozen human embryos from fertility clinics, and another that forbids the creation of human embryos for research—with derogations!

Prof. René Frydman, the “medical father” of the first French test-tube baby in 1982, admitted in a recent interview that after thirty years of in vitro fertilization, “the success rate in France is on average 17%, whereas it should be twice that.” He says that he hopes that creating human embryos for research purposes is legalized, so as to facilitate experiments to improve methods of technologically assisted reproduction. Jean-Marie Le Méné, president of the Jérôme Lejeune Foundation, warns that the CCNE advice would lead to “the liberalization of embryo research, supplied by the supposedly restricted authorization to create embryos for research purposes”. This, in his opinion, would inevitably lead to further reduction of the human embryo to a thing, an industrial material, a commodity.

Pierre-Olivier Arduin decries the already colossal “overconsumption of embryos”: on average, for every live birth resulting from in vitro fertilization, twenty embryos are conceived. He observes that although Italian, Austrian and German laws have prohibited the freezing of “spare” embryos, the success rate of IVF in those countries has not been affected. He recommends, as a matter of principle, prohibiting “the conception, the preservation and the destruction of surplus human embryos”. In response to the hair-splitting ethical distinction in CCNE Opinion #112, Arduin recalls that embryonic stem cells are obtained directly from the disintegration of a live embryo: “The research as a whole is reprehensible; you can’t separate out any one of the stages at the moral level.”

In an interview with Liberté Politique, theologian Xavier Lacroix points out that the frozen embryo does not change when her parents decide later not to implant her; the parents change their mind. “The embryo is only the victim of that change.” “Because scientific logic considers human life as a continuous process from fertilization on, ethical and legal reasoning can legitimately claim to protect that process in the name of the cardinal principle of [human] dignity.” This explanation neatly summarizes and illustrates the argument in the Introduction and First Part of the 2008 Instruction Dignitas personae by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. Lacroix, a member of the CCNE, supports Opinion #112 “with reservations”, which he and ten other members enumerated and appended to the opinion. In their view, additional questions should be addressed, which can be summarized in four points: the legal system should fundamentally forbid research on human embryos and ESCs; the dignity of a human embryo depends not on the parents’ plans but on its nature; the production of surplus embryos should be decreased and eventually halted by law; all creation of embryos for research should be ruled out.

The ones who have no qualms about proposing expanded “uses” for human embryos are also trying to mislead the legislators and restrict discussion. In a debate published in La Croix, Jean Le Méné said, “In 2004, when the time came to vote on the law, lobbying groups lied to members of parliament so that they would accept the idea of derogations. Scientists knew at the time that they would not use embryonic stem cells initially for therapeutic purposes … but it was necessary to get the MPs to accept the principle of supplying ESCs to the laboratories.” He also noted that the many interesting contributions of the États généraux de la bioéthique (a series of hearings and forums launched by former Minister for Health and Sports Roselyne Bachelot and deputy Jean Leonetti to prepare for the revised bioethics law) were being ignored: “neither their summary reports nor their communiqués to the legislators were made public.” On the other hand, in committee Leonetti moved to eliminate the criterion of “the absence of an alternative method of comparable efficacy”. This Machiavellian tactic would muzzle in advance all arguments for preferring ethical ways of experimentation, for instance using animal embryos or human adult stem cells or induced pluripotent stem cells.

Parliamentary debate on the proposed revision to the bioethics law was scheduled to begin on February 8. As that date approached, the Conference of French Bishops sent to the deputies a note formulating propositions aimed at better protection of “the dignity of all, in particular the most vulnerable” under French law. The note warns against lowest-common-denominator ethics and international pressure and condemns cryopreservation as “an unethical consequence of inadequate know-how in technologically assisted reproduction”. The law must protect human embryos “from all reification and instrumentalization”. The bishops also make two procedural observations: The new exceptions to the ban on human embryo research render the principle meaningless and seriously change the spirit of the law. Secondly, “objective information about scientific results and therapies that have been achieved would make for a first-rate parliamentary debate.”

An interdenominational Evangelical Protestant ethics committee in France found the draft bioethics law “generally prudent and wise”, but said that its proposals regarding research on human embryos “continue down the slippery slope of dehumanizing and exploiting them”. A non-religious online petition calling on philosophical grounds for a moratorium on such research was posted at www.les2ailes.com in mid-December; within the first two weeks it gathered more than 7,000 signatures.

A study published in January 2011 in the journal Cell Stem Cell calls attention to the unpredictable nature of embryonic stem cells and other pluripotent cells, which makes them inherently dangerous in clinical applications. Lead author Louis Laurent writes: “We found that human pluripotent cells (hESCs and iPSCs) had higher frequencies of genomic aberrations than other cell types. We were surprised to see profound genetic changes occurring in some cultures over very short periods of time.” Even Deputy Leonetti, who is attuned to researchers’ demands, thinks that experiments on human embryos and their derivatives are less promising than they seemed to be in 2004.

Yet scientists keep chafing against current restrictions. The Jerome Lejeune Foundation in October 2010 challenged the legality of an authorization granted by the official French Biomedicine Agency for a research program that would use human embryos to model muscular dystrophy, even though there were no “major therapeutic prospects” and an alternative method might have been just as effective.

The question now is: Will cooler heads prevail in the French parliament?

[Michael J. Miller co-translated Manual of Bioethics: General Principles by Cardinal Elio Sgreccia for the National Catholic Bioethics Center. This article is based on news summaries posted at www.genethique.org, the website of the Fondation Jérôme Lejeune. Originally published in the March 2011 issue of Catholic World Report and used by permission of the author.]