Lenten Reflection: What Is Salvation?

Shortly before his martyrdom, St. Paul penned a letter to his friend Timothy. The great apostle seems to have known that death was near, and his bittersweet words are imbued with a sense of urgency. St. Paul comforts and commends his young protégé, while exhorting him to sacrifice. “Do not be ashamed of the testimony of our Lord,” he beseeches Timothy, “but share in suffering for the gospel” (2 Timothy 1:8).

Shortly before his martyrdom, St. Paul penned a letter to his friend Timothy. The great apostle seems to have known that death was near, and his bittersweet words are imbued with a sense of urgency. St. Paul comforts and commends his young protégé, while exhorting him to sacrifice. “Do not be ashamed of the testimony of our Lord,” he beseeches Timothy, “but share in suffering for the gospel” (2 Timothy 1:8).

What is this gospel, this “good news,” for which the apostle happily suffered? It is, according to St. Paul, the revelation that God has “saved us and called us with a holy calling, not according to our works, but according to his own purpose and grace” (2 Timothy 1:9).

“Saved us and called us with a holy calling.” St. Paul’s letters abound with such language: the language of salvation. He wishes to “know nothing but Christ and him crucified” (1 Cor. 2:2), for Christ is “wisdom from God, and righteousness, sanctification, and redemption” (1 Cor. 1:30). To the Romans, he writes, “I am not ashamed of the gospel, for it is the power of God unto salvation for everyone who believes” (1:16). Likewise to the Ephesians, he speaks of the “word of truth, the gospel of your salvation” (1:13).

But what is salvation? Why is man in need of saving? And who is Jesus Christ that he should be called savior of the world?

Let us start by recognizing the obvious: there is something wrong with us. As G.K. Chesterton once quipped, man’s chronic sinfulness can be verified simply by glancing at the front page of the newspaper. It is apparent to any reasonable observer that man is radically disordered. Other creatures effortlessly fulfill the demands of their nature, but we are unable to do what we should do—what is more, we are unable to be what we should be. We are not simply beset by bad behavior: we are trapped in a sinful condition. The will is in bondage to a dark, strange force.

The modern psychiatrist may call this “force” the id. In Freud’s words, the id is the “dark, inaccessible part of our personality … a cauldron full of seething excitation … where contrary impulses exist side by side.” The Christian calls this force the “law of sin” (Romans 7:23), which St. Paul describes from first-hand experience, “I do not do what I want to do. Instead, I do the very thing I hate” (Romans 7:15). Call it what you will: this deep-seated perversity infects every dimension of man’s existence, so that we find ourselves constantly embroiled in conflict and ceaselessly battered by the passions.

We must not think that our corruption—our “fallen nature”—is the work of God. The Lord created the world and it is very good. He placed man at the pinnacle of creation. We possessed not only God’s image—reason and will—but also the gift of supernatural life. This supernatural life was a share in the divine nature, and it filled man with the sanctity and charity of God. In this state of “original justice,” we enjoyed fellowship with the Lord, and the body, mind, and soul worked in perfect accord, so that we exercised virtue with ease.

Tragically, this peace was shattered by the fall: seduced by the devil, our first parents abused their freedom, preferring themselves to God. The Church wisely refrains from dogmatizing the details of the fall. The Catechism tells us simply that the Bible “uses figurative language, but affirms a primeval event, a deed that took place at the beginning of the history of man” (390)

On account of this fall, we call man’s nature “fallen.” This is not to say that it is totally depraved. The image of God remains, although our natural powers, both moral and intellectual, are seriously compromised. However, our supernatural righteousness is gone, so that we are born devoid of sanctifying grace and deprived of our share in the divine life. Fallen man remains capable of purely natural virtue, like courage and friendship, but he is unable to “make any right choice relating to the salvation of eternal life” (Council of Orange, Canon VII) apart from the illumination of the Holy Spirit.

Everyone born of Adam inherits Adam’s grievous wounds, which are healed only by faith consummated in baptism. Why do all suffer for the first parents’ sin? The answer lies in the solidarity of mankind, a great mystery indeed. Envision our race as one body descended from a single head, Adam. As the stem shares in the disease of the root, so the body shares in the sin of the head. We are all inheritors of original sin, and this fundamental crookedness inclines us to further transgressions, so that we worsen our lot by our own will, adding insult to injury.

Needless to say, this terrible lot was unacceptable to God, who loves mankind. The holiness of God is founded upon the “rectitude of divine love” (Catechism, 1991), for “God is love” (1 John 4:8). As the Lord declared through the prophet Isaiah, “Though your sins are like scarlet, they shall be as white as snow; though they are red like crimson, they shall become like wool” (1:18). Because of his superabundant love, God freely chose to create man, that we might share in the delight of existence and glorify his name; because of his superabundant love, God freely chose to recreate man in Jesus Christ, that we might not perish but have eternal life.

While it was not appropriate that God should allow his handiwork to languish in sin and death, neither was it fitting that God should forgive man without punishing and rectifying our offenses. Such an unwarranted dismissal would constitute a denial of justice: that is, a denial of God’s very self—unthinkable! For God is a God is justice: “I the Lord love justice; I hate iniquity” (Isaiah 61:8). Anyway, how would the mere pardoning of sins profit a race infected by death and ensnared by wicked powers?

The redemption of man demanded a remedy that would satisfy simultaneously the mercy and the justice of God, while liberating man from bondage to corruption and restoring his supernatural life. But who could fulfill such a role? No wonder Job lamented, “How can a man be righteous before God? … For [God] is not a man, as I am, that I might answer him, that we should come to trial together. There is no mediator between us, who might lay his hand on us both” (9:1, 32-33).

Thanks be to God that a mediator, a remedy, came in the figure of Jesus of Nazareth: the incarnate Word of the Father; one person in two natures; Son of God and Son of Man; truly divine, truly human; priest and victim.

Through the incarnation, the chasm between God and man was bridged, and we were made “partakers of the divine nature” (2 Peter 1:4). As God, Christ healed human nature, establishing it anew; as man, Christ served the Father with perfect love, making reparation for the waywardness of Adam. “For just as through the disobedience of one man many were made sinners, so also through the obedience of one man many will be made righteous” (Romans 5:15). He was God to man and man to God. “All the promises of God find their ‘Yes’ in him. That is why it is through him that we utter our ‘Amen’ to God for his glory” (2 Corinthians 1:20).

Christ’s entire existence was an act of thanksgiving, a “living sacrifice” (Romans 12:1) to his Father. “When Christ came into the world, he said, ‘Sacrifices and offerings you have not desired, but a body have you prepared for me; in burnt offerings and sin offerings you have taken no pleasure. Then I said, ‘Behold, I have come to do your will, O God” (Hebrews 10:5-7).

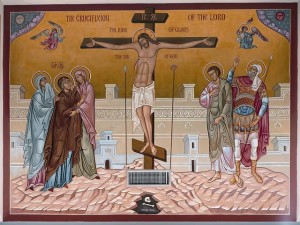

Christ consummated his righteous life by submitting to death, death on the cross. This was not an act of destruction so much as consecration. In the life and death of the man Jesus, the whole of mankind was given over to God the Father in perfect love and obedience.

Jesus’ self-oblation—valuable by virtue of his divinity, appropriate by virtue of his humanity—fulfilled God’s justice and established his mercy. The cross provided abundant satisfaction for sin, for upon it perished a man with the dignity of God. Having answered his own call to justice, God was free to exercise his lovingkindness without violating the integrity of his moral law or the consistency of his nature. St. Paul exclaims, “God made him who had no sin to be a sin offering for us, that in him we might become the righteousness of God” (2 Corinthians 5:21).

Christ was crucified in our stead. He was—he is—our substitute, our representative. The penalty of sin is death, for God, the fountain of life, has no fellowship with sin. “God is light and in him there is no darkness” (1 John 1:5). To sin is not only to offend God, but also to break communion with him—to invite death into our innermost being. For our crimes, we deserved punishment and death, in this life and the next.

Jesus took upon His scourged and pummeled shoulders the sins of the world. The incarnate Word gathered up the sins of man in his flesh, and destroyed them in the purifying fire of his divinity. “By his stripes we are healed” (Isaiah 53:5). His charity overcame our hatred; his righteousness destroyed our wickedness. Where we had loved ourselves at the expense of God, Christ loved God at the expense of himself.

The Head suffered so that the Body might be spared—and not just spared, but rewarded. St. Thomas Aquinas explains, “The head and members are as one mystic person; and therefore Christ’s satisfaction belongs to all the faithful as being His members” (Summa Theologica, 3, 48, 2). Pope St. Leo explains the atonement thusly: “By a wondrous exchange [Christ] entered into a bargain of salvation with us, receiving ours and giving his: honor for insults, salvation for pain, life for death” (Homily for Good Friday).

Christ became, through his life, death, and resurrection, the new and perfect Adam. He is man as man is meant to be. Those who belong to him enjoy the benefits of his work, which he brings to fruition in their hearts through the work of the Holy Spirit in the sacraments. Because the Son of God humbled himself, we are exalted. By his sweet yet dreadful labor, we are saved from wrath and made sons of God, heirs to the eternal kingdom.