The Pope Who Confronted the Modern World

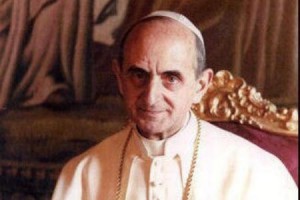

A third 20th Century pope advances toward sainthood this weekend with the beatification of Giovanni Battista Montini, Pope Paul VI (1963-1978).

A third 20th Century pope advances toward sainthood this weekend with the beatification of Giovanni Battista Montini, Pope Paul VI (1963-1978).

In canonizing Popes, the general rule is that we raise men to the honor of the altars and not papacies. Pope Montini, however, is so inextricably linked with the Second Vatican Council, over whose conclusion and implementation he presided, that it is hard to separate the pontiff from the pontificate.

Critics charge that Paul ceded too much to modernity in the reforms of the Council. Too much ink has already been spilt on that question and the subject is too dense to treat here. We will limit ourselves to quoting his NYT obit: “If there had been no Second Vatican Council begun under John XXIII,” the Times mused, “it is unlikely that Paul VI would have proposed such an updating of the church.”

Still, Pope Paul seems to be the ultimate “modern” pontiff. There he was jet-setting around the world. There he was speaking at the U.N.—the first pontiff to do so. And there he was watching the live television broadcast of the moon landing.

Atmospherics notwithstanding, the relevant aspect of Paul’s interaction with the contemporary world is that he looked upon the Modern Age and he declared it a fertile subject for our two-thousand year-old faith.

Pope Paul looked into the Petri dish and he recognized the presence of God in the microscopic manifestation of human life at the moment of conception. His encyclical “Humanae Vitae” is a triumph of Christian ethics over the Scientific Age, and immediately became a symbol both of Catholic identity and of the cultural contradiction that typifies an authentic expression of the faith.

Pope Paul also looked at modernity at the macro level, and declared that geopolitics and the world economy were also subject to Christian ethics, promoting the Social Doctrine of the Church in his encyclical “Populorum Progressio” (which Benedict XVI declared “the Rerum Novarum of the present age”) and in his apostolic exhortation “Evangelii Nuntiandi” (which Francis described as “the greatest pastoral document that has ever been written”).

The Venerable Montini was so steeped in our time that he even appears “modern” in his faults and shortcomings. The first pope to be so publicly psychoanalyzed, Paul was criticized for a brooding disposition and indecisiveness. In fact, he was believed to suffer bouts of depression.

If his challenges were oh-so-modern, he relied on age-old defenses to confront them. He was a Marian devotee, the first pope to make a pilgrimage to Fatima, and he inserted the largest synthesis of marian doctrine in the Dogmatic Constitution on the Church, “Lumen Gentium.” He made other pilgrimages, including to the Holy Land, and was known as “the Pilgrim Pope.”

“In each of us, there is a struggle going on inside,” said Paul explaining his spirituality. Our weakness, he explained, which is called miseria, meets the Love of God and forms a new word, misericordia, which means Mercy, and it is this Mercy through which God sends his Son to mend our brokenness, and redeems us.

Venerable Paul VI, now to be Blessed Paul VI, encountered the misery of the modern age and bathed it in the light of God’s mercy.