Flannery’s Existentialist Stamp

In one of his last works before his masterpiece, The Brothers Karamazov, Dostoyevsky wrote The Dream of a Ridiculous Man. In this story, the narrator goes to another solar system and lands on a planet where the inhabitants are people just like us, but untainted by the Fall in the Garden. They live, the narrator tells us, “in the same paradise as that in which…our parents lived before they sinned.” But the narrator, being a fallen man, corrupts the inhabitants: “Like the germ of a plague infecting whole kingdoms, I corrupted them all.”

In one of his last works before his masterpiece, The Brothers Karamazov, Dostoyevsky wrote The Dream of a Ridiculous Man. In this story, the narrator goes to another solar system and lands on a planet where the inhabitants are people just like us, but untainted by the Fall in the Garden. They live, the narrator tells us, “in the same paradise as that in which…our parents lived before they sinned.” But the narrator, being a fallen man, corrupts the inhabitants: “Like the germ of a plague infecting whole kingdoms, I corrupted them all.”

As beings corrupted by Original Sin, they begin to act like us on earth. In the words of Russian literature professor Arthur Trace: “They invent morality because now there was immorality; they make a virtue of shame, whereas before they had no need for shame; they invent the concept of honor because now there is such a thing as dishonor; they invent justice because now there is injustice; and they invent brotherhood and friendship because there is hatred.”

In short, on the unfallen planet, there was no virtue or morality because there was no vice or immorality in contrast. There was no distinction between bad and good. It was a morally-existentialist world: No essences; just existence.

We’ve reached a similar point in our culture, where the moral essences, like bad and good, no longer carry meaning. But it’s not because we’re the perfect planet of the Ridiculous Man. I fear it’s because we have deviated so far from that perfect planet that we’ve come full circle to a similar situation.

This is the point of Flannery O’Connor’s fiction.

Flannery’s Characters

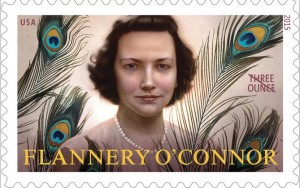

Flannery O’Connor is to modern literature what Marilyn Monroe is to the movie industry: A quick, shooting-star streak of brilliance in the 1950s that died out prematurely in the early 1960s, not yet forty years old. Although O’Connor snagged the public’s attention with her fiction’s intense violence, it was her deep and perplexing characters that caught the attention of the literature establishment.

Her most-celebrated story “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” for instance, tells the story about a vacationing family that is murdered by an escaped convict who calls himself the Misfit. The story revolves around the Grandmother’s relentless chatter, which ends up getting the family killed (shortly after running into the Misfit, she recognizes him and blurts out his identity—the Misfit acknowledges it and tells her it would’ve been better for the family if she hadn’t recognized him).

As the Misfit’s crew takes one family member after another into the woods and shoots them, the Grandmother chatters away at the Misfit in hopes of saving her life, throwing all sorts of Christian clichés at him, which the Misfit (an intelligent, though warped, man) bats away with intellectual ease. The misshapen form of the characters’ souls—the Grandmother’s self-obsession and the Misfit’s nihilistic detachment—are apparent, in their words and actions.

The story ends when the Grandmother finally puts aside all her chattering clichés and speaks to the Misfit openly, authentically, and prepares to embrace him as one of her own children. The Misfit responds by pulling out his revolver and shooting her in the chest.

O’Connor later said the story’s violence is merely a means of showing the hearts of the characters. The violence shakes the Grandmother (a woman with over seventy years of selfish armor surrounding her heart) and breaks open her chattering cover to expose her interior, like an earthquake breaks open a building.

The action, O’Connor explained, is in the Grandmother’s soul, not in the violence: “Now the lines of motion that interest the writer are usually invisible. They are lines of spiritual motion. And in this story you should be on the lookout for such things as the action of grace in the Grandmother’s soul, and not for the dead bodies.”

As I read her fiction at first, I asked myself, “Did she entertain thoughts like those? She must have, or else she couldn’t have come up with all the twisting and turning that goes on in her characters’ dwarfed souls.” But I don’t think she entertained those thoughts as much as she visited those thoughts by plunging herself into her character’s soul until she could look from the inside at the essences swarming around the existential core.

In order to do this, she would have had to put aside her own self and inner thoughts, so she could look deep into her characters’ self and inner thoughts—just like any artist must do. She touched on this in her essay, “The Nature and Aim of Fiction,” when she wrote:

Usually the artist has to suffer certain deprivations in order to use his gift with integrity. Art is a virtue of the practical intellect, and the practice of any virtue demands a certain asceticism and a very definite leaving-behind of the niggardly part of the ego.

O’Connor’s art was a self-emptying, self-forgetting, leaving-behind of the self. Through this self-emptying, she was able to see into the souls of others and produce characters whose psychological twistings are captivating because they reveal a jangle of essences that hollowly clang against one another in today’s world, a world where essences have increased and multiplied and have all but killed the role of existence.

Flannery and the Mafia

In my favorite mob movie, GoodFellas, the main character and narrator, Henry Hill, at one point is explaining the term “goodfella.” He says if you’re one of “them,” you’re a goodfella. A goodfella knows the ropes, understands to keep quiet, is willing to conduct a heist, likes to gamble and drink.

The term “good” obviously lacks any real meaning in the mob’s usage, but its use of the term isn’t necessarily wrong.

As many philosophers have pointed out, evil is nothing but the absence of reality. By this they mean: If a good God created the Earth, then everything on it must be good. If He is a truly good God, he wouldn’t create evil, and, because He creates all things, evil must just be an absence of the goodness and full being bestowed by God. That’s why the philosophers often refer to evil as “privation of being.”

Now, the Mafia is evil: It exists to carry out sin. It has no other reason to exist, and therefore, perhaps more than any other group I can think of, is properly labeled “evil.”

In an evil thing like the Mafia, you aren’t dealing with reality. You’re dealing with a privation. As a result, words—the symbols that point to underlying reality—become nearly meaningless when describing it. I think of it like hauling a big empty box into the street and telling one person that there’s a luxury car in it and another person that it’s full of excrement. You’re equally close to the truth either way.

Hence the use of the term “good” to describe an evil privation like the Mafia is, in a warped way, alright. And this is basically what happens in O’Connor’s fiction. Thomas Merton observed of O’Connor’s fiction that the “‘good,’ the ‘right,’ the ‘kind’ do all the harm. ‘Love’ is a force for destruction, and ‘truth’ is the best way to tell a lie.”

Essences normally have meaning, but O’Connor’s characters are individuals whose existential cores have shrunk to minimal proportions and who live on a conglomeration of essences that substitute for, and over-run, any substantive existence. But existence takes revenge on the essences because, by shrinking to nothing, it gives the essences nothing to work with. As a result, the essences themselves become meaningless because they are multiplied against an existential privation, and the product of anything multiplied by nothing equals nothing.

Ironically, the resulting linguistic situation is similar to the Ridiculous Man’s perfect planet. In both worlds, distinctions between virtue and vice aren’t meaningful. In a perfect world of simple, unfallen existence, the essences aren’t even named, being in complete harmony with existence. In a badly marred world, a fallen world whose fall has been exacerbated by more and more sin, there are only essences, but the terms describing them have become meaningless.

In the perfect world, the essences multiply against a unified existence, resulting in a product of one. All is one. In the badly marred world, the essences multiply against an existence that is, for all practical purposes, zero, resulting in a product of zero. All is nothing.

And the latter is about where we are today, as well-magnified by looking at the idols of mass society. The public personas of mass society aren’t real. They are hollow men. Their essences and forms multiply against nothing to produce nothing, just like the characters in O’Connor’s stories. They are nothing and their characters are nothing; their characteristics are a jumbled mess.

They have what I call “zero soul,” a soul that is incapable of giving a moral product. For the zero soul, all labels are meaningless. The “good” things (ambition, money, cars) are often bad; the “bad” things (simplicity, obedience, silence) are really good.