Newman: The Praise of Men

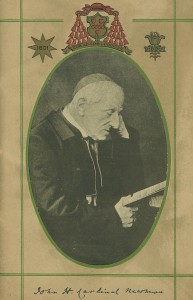

Bl. John Henry Newman, 1880

In the sermon The Praise of Men,1 after indicating that ridicule is a powerful weapon used by the devil, Blessed John Henry Newman describes a case in which it is the cause of much pain: when a person who had shunned religion turns by God’s grace back to the practice of religion and meets the scorn of former friends. He writes, “Nothing is more painful in the case of such persons, than the necessity often imposed upon them of acting contrary to the opinion and wishes of those with whom they have till now been intimate, —whom they have admired and followed.”

Newman does not advise such a person to break off necessarily from former friends, but he must not accept any wrongdoing. Furthermore, he warns of the suffering to be faced: “he will incur the ridicule of his companions. He will have much to bear. He must bear to be called names, to be thought a hypocrite, to be thought to be affecting something out of the way, to be thought desirous of recommending himself to this or that person. He must be prepared for malicious and untrue reports about himself; many other trials must he look for.”

It is likely that the Oxford clergyman was writing from his own experience of being ridiculed for his religious beliefs. As he gradually found the doctrinal claims of the Roman Catholic Church to be stronger than those of the Anglican, and moved towards the Catholic Church, he incurred mockery and false accusations. He forgave the authors of such abuse and prayed for them.

In the sermon, he encourages the person who is the object of such treatment to pray to God for meekness and for those who ridicule him, and to consider that he deserves the ridicule, once having been like those who ridicule him.

St. Josemaría Escrivá offers the following sobering remark: “When you hear the plaudits of triumph, let there also sound in your ears the laughter you provoked with your failures.”2

Newman continues, “Let him see to it that he acts as well as professes. It will be miserable indeed if he incurs the reproach, and yet does not gain the reward.” St. Peter teaches us that bearing this reproach is pleasing to God: “For what glory is it, if when ye be buffeted for your faults ye shall take it patiently? But if, when ye do well and suffer for it, ye take it patiently, this is acceptable with God.” [1 Pet 2:20]

Newman reminds his listeners that they are in the sight of God and the angels whose praise alone they should seek: “St. Paul charges Timothy by the elect Angels; and elsewhere he declares that the Apostles were made “a spectacle unto the world, and to Angels, and to men.” [1 Cor 4:9] Are we then afraid to follow what is right, lest the world should scoff?”

The Oxford don offers a practical suggestion to all of us: “Accustom yourselves, then, to feel that you are on a public stage, whatever your station of life may be; that there are other witnesses to your conduct besides the world around you; and, if you feel shame of men, you should much more feel shame in the presence of God, and those servants of His that do His pleasure.”

Each one would do well to ask himself: How do I react in the face of ridicule? Whose praise do I seek? And do I seek the praise of men more than that of God? The saints teach us to humble ourselves. We should pray like St. Josemaría: “The more I am exalted, my Jesus, the more you must humble me in my heart, showing me what I’ve been and what I’ll be if you forsake me.”3

[1] John Henry Newman, Parochial and Plain Sermons, Vol. VII, The Praise of Men.

[2] Josemaría Escrivá, The Way, 589.

[3] The Way, 591.