How Two Sacred, Bloody Images Take Us to God

One year ago, on May 23, 2010, the Holy Shroud of Turin was placed out of public view at St. John the Baptist Cathedral in Turin (Torino), Italy. We are not expected to see it again until the year 2035. For only the 18th time in its 2,000 year history, the Church’s most venerated relic was allowed to be seen by the public. Never did I imagine I would be among the two million pilgrims who came from all over the world to look at the Man in the Shroud last spring. Also along with me was my newly-confirmed 14-year old daughter Teresa and two of her friends. It will be 34 years before any of us will be able to see it again. I will be an old man then; I like to think my three fellow travelers will be drawn back.

One year ago, on May 23, 2010, the Holy Shroud of Turin was placed out of public view at St. John the Baptist Cathedral in Turin (Torino), Italy. We are not expected to see it again until the year 2035. For only the 18th time in its 2,000 year history, the Church’s most venerated relic was allowed to be seen by the public. Never did I imagine I would be among the two million pilgrims who came from all over the world to look at the Man in the Shroud last spring. Also along with me was my newly-confirmed 14-year old daughter Teresa and two of her friends. It will be 34 years before any of us will be able to see it again. I will be an old man then; I like to think my three fellow travelers will be drawn back.

I first heard about the Shroud the year my wife Patti and I were married in 1981. Since then, I have dug deep into the mystery, history and science of this remarkable relic that has been venerated for centuries. In the year since returning from Italy, I have spoken before Catholic schools and Catholic groups with a PowerPoint presentation that delves into what this enigmatic image on this ancient cloth tells us about the sufferings of Jesus Christ.

For those who are a little unsure of what the “Shroud of Turin” is, let me give you a very basic description and the rest of the article will tell you what I have learned in the last 30 years. The Shroud is a gruesome reversed photograph of a man murdered on a cross. As Catholics, we would never have to believe that Shroud is truly the one placed on Our Lord when he was prepared for the tomb on Good Friday. The Church is careful not to give an outright endorsement – no more than it would to any other of its treasured relics. And yet, Pope Benedict XVI himself paid a visit to Turin last year. He remarked that the Shroud is an icon, “written with the blood of a crucified man in full correspondence with what the Gospels tell us of Jesus.”

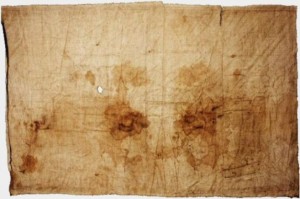

During the last year the Shroud has drawn me to learn more about the Sudarium of Oviedo. This is believed to be the actual facecloth placed over Christ’s head as he was laid out in the tomb. Some think the Shroud of Turin only could date as early as 1190 because of the infamous Carbon-14 date test (discussed below). The history for the Sudarium is known more reliably. The Sudarium was inside a chest of relics whisked away from Jerusalem when it was conquered by a Persian king in the 7th century. The chest, with the Sudarium, ended up in several Spanish cities, being carried northward for safety as the invading Muslim armies took over southern Spain in the 8th century, eventually ending up in extreme northern Spain at Oviedo in 840.

During the last year the Shroud has drawn me to learn more about the Sudarium of Oviedo. This is believed to be the actual facecloth placed over Christ’s head as he was laid out in the tomb. Some think the Shroud of Turin only could date as early as 1190 because of the infamous Carbon-14 date test (discussed below). The history for the Sudarium is known more reliably. The Sudarium was inside a chest of relics whisked away from Jerusalem when it was conquered by a Persian king in the 7th century. The chest, with the Sudarium, ended up in several Spanish cities, being carried northward for safety as the invading Muslim armies took over southern Spain in the 8th century, eventually ending up in extreme northern Spain at Oviedo in 840.

The chest with the Holy Relics was not even opened until the 11th century. For three centuries, a huge chest containing relics from the Holy Land was venerated, but the contents were only passed down orally through the centuries because contents were deemed too holy to be seen. Finally, after many days of prayer, fasting and the wearing of sackcloths, King Alfonso VI had the chest opened and a catalog made of what was inside. One of the items was the Sudarium, the bloody cloth that was placed on Jesus Christ when he was laid out in the tomb. The key biblical passage is, John, chapter 20, verses 6 and 7, “Simon Peter, following him, also came up went into the tomb, saw the linen cloth (The Shroud of Turin) lying on the ground, and also the cloth that had been over his head (The Sudarium) that was not with the linen cloth but rolled up in a place by itself.”

The chest with the Holy Relics was not even opened until the 11th century. For three centuries, a huge chest containing relics from the Holy Land was venerated, but the contents were only passed down orally through the centuries because contents were deemed too holy to be seen. Finally, after many days of prayer, fasting and the wearing of sackcloths, King Alfonso VI had the chest opened and a catalog made of what was inside. One of the items was the Sudarium, the bloody cloth that was placed on Jesus Christ when he was laid out in the tomb. The key biblical passage is, John, chapter 20, verses 6 and 7, “Simon Peter, following him, also came up went into the tomb, saw the linen cloth (The Shroud of Turin) lying on the ground, and also the cloth that had been over his head (The Sudarium) that was not with the linen cloth but rolled up in a place by itself.”

Like the Shroud, the Sudarium has been studied by science. Scientific studies have shown that the Sudarium and the Shroud were in contact with the same AB blood. There were over 120 points of match between the blood wounds on the Sudarium and the Shroud. With a complete match for the cap of thorns placed on Christ’s head. The best explanation for why there is no reversed image on the Sudarium like the Shroud is that it was likely removed before Jesus was shrouded. It explains why it was folded and not with the linen cloth when Peter and others entered the tomb.

The Sudarium of Oviedo measures 40 by 24 inches and is kept in the Cathedral of Our Savior in a small chapel that was built especially for the chest of relics in 840 in Oviedo, Spain. It is brought out on display three times a year. Good Friday, the Feast Day of the Triumph of the Cross, September 21, and its octave, September 28. This is the feast date, celebrated since the 4th century, in which the Church celebrates St. Helen’s miraculous discovery of pieces of the True Cross when she went on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Originally among the relics inside the chest on Oviedo were pieces of the True Cross.

What Do we Know about the History of the Shroud of Turin?

The Shroud of Turin is a 14-foot long by 3.3-foot wide linen cloth that bears the faint image of a crucified man. Millions believe that man to be Jesus Christ. It is said to be the most scientifically studied Church relic ever. And still the origin of this image is debated among scientists, historians and theologians. While no one would ever be required to “believe” that the Shroud of Turin is the actual burial cloth of Jesus Christ, one thing is clear: to this day none of the skeptics can accurately tell us how this bloodstained, linen cloth came to bear the image of a photographic negative of a crucified man.

There is clear and convincing proof in the body of scientific evidence in favor of the belief that the Shroud is the actual burial cloth of Christ. Ever since 1898 when Italian photographer Secondo Pia discovered that the image was actually reversed, as in a photographic negative, scientists have attempted to unravel its mysteries. The more we peel back its layers, the more mysterious the Shroud becomes and lives up to one of its earliest descriptions when it was known as “an image not made by human hands.”

While in Turin last spring I was able to tour several museums and get my hands on several excellent reference guides about the Shroud and its history. Here’s what scholars tell us are the places the Shroud has been from the known historical records. (This is also backed up by the scientific information that is pointed below).

This description of “an image not made by human hands” first comes to us in references about an ancient cloth said to bear a facial image of Jesus Christ. It was known as the Image of Edessa, the Edessa Cloth and later during the Byzantine Era as the Holy Mandylion. Edessa was a great city during the time of Christ, now known as Urfa in modern day Turkey. There is a high level of certainty amongst scientists, religious scholars and historians that the Shroud of Turin is the cloth referred to as the Image of Edessa.

It is said that this facial image on a cloth came to Edessa to King Abgar V Ouchama of Edessa (13-50 AD) by the Apostle Thaddeus. This was documented in Eusebius of Caesarea’s early 4th century Ecclesiastical History. He writes about a document once in Edessa’s archives that had been written by King Abgar V and delivered to Jesus by an envoy. The King asked Jesus to come to Edessa and to cure him of leprosy. The history reports that the Apostle Thaddeus was sent sometime after Jesus’ death and that he founded a church in Edessa. A separate Syrian manuscript, the Doctrine of Addai confirms these details and adds that a “portrait” of Jesus accompanied Thaddeus. It referred to the Edessa Cloth as a “tetradiplon.” A tetradiplon means a cloth doubled in fours, so that only the face in the cloth is visible. King Abgar was cured of his leprosy. Following the King’s miraculous cure his kingdom was converted to the new Christian faith. Others comes to see this Image of Edessa and are converted as well over the centuries (much in the way Our Lady of Guadalupe would convert millions centuries later in the New World).

But after four centuries the people begin to lose their faith and those who were in possession of this Image hid it inside the walls above one of the city gates in Edessa. They were fearful that it would be destroyed. The cloth was eventually lost, or forgotten about, until the year 544 AD when it was rediscovered during a Persian invasion and placed in a new Church built especially for it. In the late 6th century Evagrius Scholasticus’ Ecclesiastical History mentions that Edessa was protected by a “divinely wrought portrait” sent by Jesus to King Abgar. In 730 AD St. John of Damascus in his book On Holy Images talks about the cloth as a “himation”, which is translated as “an oblong cloth or grave cloth.” This is the first time we can be certain that the historical references are not simply to an image of the face of Jesus, but in fact an entire image of the crucified body of Christ.

In 944 AD there was an attack on Edessa again, this time from Muslim invaders. The Cloth of Edessa was transferred to Constantinople, the Byzantine capitol city now known as Istanbul in Turkey. When the image arrived the Archdeacon of the Hagia Sophia Cathedral preached a sermon about the cloth being a burial cloth, believed to be that of Jesus and that it contained bloodstains. There are several historical documents that referred to the Image over the next 250 years.

In 1204 the Shroud disappears from Constantinople when the city is sacked by Knights of the Fourth Crusades. The Knights seized numerous relics because of the invading Muslims and once again removed the Shroud. In 1207, Nicholas d’Orrante, Abbott of Casole and the Papal Legate in Athens wrote about the relics taken from Constantinople by the Knights and referred specifically to the Shroud saying that he saw it “with his own eyes” in Athens.

A French knight, Geoffrey de Charny, was the first identified owner of the Shroud after this time and he wrote to Pope Clement VI that he wanted to build a church at Lirey, France for the Shroud. The year was 1354. Large crowds came to visit the church at Lirey to view the Shroud and special medallions were struck. I saw one of these medallions at the Turin Museum and it depicts an image of the Shroud. The Shroud remained in the De Charny family for about 100 years until it passed to the Savoy family.

By 1532 the Shroud had been moved to several different locations for security and veneration reasons. That was the year the Shroud suffered fire damage in the St. Chapelle Chapel in Chambery, France. It had been located there since 1453. Burns to the cloth resulted from molten silver from the reliquary box in which it was stored and produced symmetrical marks in the corners of the folded cloth. Poor Clare nuns attempted to repair this damage with patches. There were also a number of water stains caused by the extinguishing of the fire.

In 1578 the future Saint and then Cardinal Charles Borromeo wanted to take the dangerous journey on foot, over the Alps, from Milan, Italy to Chambery, France to give thanks in front of the Shroud in thanksgiving for Milan having been mostly spared from the ravages of the plague. To save Cardinal Borremeo such a journey across the Alps, the owners of the Shroud ordered that it be transferred to Turin. It has remained in Turin ever since.

What do we Know about the Science of the Shroud?

It would take several books or websites to get into all the scientific testing that has been done on the Shroud of Turin. (And there are, indeed, several dozen books and websites devoted to the science of the Shroud, posted at the end of this article). Suffice to say that the real testing began in 1978 when several scientists were given access to Shroud for five days. It is known by the acronym, STURP or Shroud of Turin Research Project.

For 120 hours, in 1978, the STURP scientists photographed, x-rayed, pressed sticky tape, took samples from the bloodstains, did spectra analysis tests and snapped thousands of photomicrographs of the Shroud. Three years later they released their findings, and more than 30 years later their study has not been notably contradicted. Among the STURP findings: No pigments, paints, dyes or stains were found on the fibrils of the linen cloth. It is not a painting. An image analyzer shows the Shroud has a unique, three-dimensional codex embedded in it, unlike any other two dimensional image made by humans. While some explanations of what caused the image on the Shroud are possible from a chemical point of view, there are precluded by physics and certain physical explanations are conversely completely precluded by the chemistry. To explain the Shroud image there must be a complete explanation from a physical, chemical, biological, and medical standpoint. To date no one has presented this complete solution. It is an enigma.

The best scientific explanation is that the Shroud image was produced by something which resulted in “oxidation, dehydration and conjugation of the polysaccharide structure of the microfibrils” of the linen itself. STURP concluded that for now that the “Shroud image is that of a real human form of a scourged, crucified man. It is not the product of an artist. The blood stains are composed of hemoglobin and also give a positive test for serum albumin.”

The scientists also determined that there is evidence on the Shroud to show that it has pollen on it that can be traced to all the known locations at the specific times in its history: from Jerusalem to Edessa to Constantinople to Athens to locations in France and Italy.

In 1988 Carbon-14 tests seem to indicate that the cloth was dated to between 1190 and 1350 AD. This led some to believe it was a clever medieval forgery. But since that time those results have been called into question on a number of levels and now the Carbon-14 tests themselves have been largely discredited.

Reflections on our Days in Turin, 2010

When I originally booked our free Shroud of Turin tickets online in the United States before flying to Italy, I had hoped to have at least 3 or 4 viewing times and spend at most 10-12 minutes total in front of the Shroud. God had other wonderful plans for us. After a 30-hour odyssey of flying from our homes in North Dakota, making train connections through Rome to Milan and Turin, checking into our B and B and then hiking 20 minutes on the ancient cobblestone streets and plazas of Turin, we finally had our first chance to stand in line with others to see the Shroud of Turin. Coming up to St. John the Baptist’s Cathedral, the early evening sun lit up the old dome perfectly and we found out where to line up to prepare for our viewing. I had expected to wait for hours. In just over 20 minutes we were ushered into the sanctuary and beheld the Shroud.

The Man in the Shroud seemed to be very real, profound, serene, surreal, peaceful and holy. I felt a tear in my eye as I prayed both in thanksgiving for being there (it is good to be here Lord, I remember saying!) and for the love that Christ outpoured for his creatures during his time on the Cross.

The next day we went to Mass at one of the 68 Catholic churches that are nearly everywhere you walk in old Turin. By chance it was the church of St. Charles Borremeo, dedicated to him in 1609, the former Archbishop and Cardinal from nearby Milan who, by wanting to hike to France to see the Shroud, is credited with having it being brought to Turin in 1578.

Following Mass we made our way to the Shroud Museum. Inside were remarkable photos, paintings and depictions of where the Shroud is believed to have been through the last 20 centuries. For those who wonder if the Shroud was a medieval forgery, there were plenty of scientific and contemporary records through the centuries to show that the Shroud has indeed existed since the time of the burial of Christ.

After a brief lunch we walked the few blocks to get in line to see the Shroud again.

And just like the evening before, we were ushered into the darkened Cathedral of St. John the Baptist to be given a chance to stand six feet from the “image not made by human hands.” We then decided to visit the Turin Diocesan Museum located underneath the Cathedral. It was a choice that my daughter Teresa and her two teenage girl friends fought me on a bit, because we had already seen the Shroud Museum and they “strongly” felt that they wanted to wander around more and perhaps do some shopping for presents to take home to family and friends. I insisted on seeing this museum. And like all things, God was guiding us this trip and He had a happy surprise for us following our museum tour.

The Turin Diocesan Museum contains samples of the architecture, art and archeology of the Cathedral that dates back through the last 18 centuries. We learned that the Cathedral was founded during the very earliest Christian times and built next to the existing Roman walls at the side of a theater, the ruins of which are still visible under the massive Cathedral.

At the end of the tour we came out of the Cathedral basement and were led back to the front steps. Behind us was that same line of people waiting to get in to see the Shroud. However, this time the doors to the Cathedral were open and people were walking inside to the main body of the Church, so we looked at each other and followed them inside.

I had wondered about the people behind us in the pews in the main body of the Cathedral who were kneeling and praying when we came down the side aisle and had our three minutes in front of the Shroud earlier in the day and the evening before. I thought you needed special permission, or had to have a special pass. Turned out you don’t need anything at all. While you were not six or ten feet away from the Shroud, you still had a wonderful view and could be as close as 25 feet.

And so my daughter Teresa and her friends found out that by going to the Diocesan Museum, somewhat against their will, they were able to sit, kneel and even stand for well over a half hour as we venerated this mysterious Shroud. We watched the comings and goings of thousands of pilgrims, like we had been, and listened to that beautiful Italian prayer over and over again said so reverently each time for each new group of pilgrims. We prayed rosaries, said Chaplets of Mercy and just sat in silence, knowing what a special 30 minutes we all were having together.

As we left we found out that Mass was said there at 7 a.m., and so we planned to be back the next day.

Mass in Front of the Shroud of Turin

There are certain Masses we all remember. Some of us remember our First Communion, Confirmation, Marriage and other special ones. I will always remember the day when I took part in a Mass, concelebrated by 10 Italian priests, in front of the Shroud of Turin at St. John the Baptist’s Cathedral in Italy.

Attending this Mass gave me a sense of wonderment when I realized where this linen cloth has purported to have been these last 20 centuries. How many people have stood before this bloodstained and ancient cloth? How many received the body and blood of Christ in front of this holy cloth? Christ’s last moments before passing into His eternal reward are mysteriously etched onto the Shroud. The Apostles were the first to see this linen cloth, King Abgar then was cured of his leprosy and its journey from there has meant it has been at Mass before literally millions of the faithful through 20 centuries. I couldn’t help but think when Peter entered the empty tomb and saw this linen cloth lying inside “and believed,” could it have been this imprint I was looking at on the Shroud that helped him and the others overcome their initial unbelief?

Here I was at a Church built on a site of earlier Catholic churches that dated back to the 3rd century. Mass has been said here for well over 1800 years. At the precise moments when the priest lifted up the bread and wine to confect them into the Body and Blood of Christ, my eyes lined up with the Shroud through the Eucharist. There were the bloodstains, there was the crucified body, and there was our Creator who suffered, died and was buried for all of us. Emotionally and spiritually I knew that communion would never, ever be the same for me again.

We are the body of Christ. There was the body of Christ. Transubstantiated by the Italian priests and physically represented in one of the Church’s most venerated relics. The choir began to sing angelically as we all went up to receive, with my eyes focused again on the Shroud. Then the Mass at St. John the Baptist Cathedral was over. I walked forward to the front pews to kneel and say a Rosary and a Chaplet of Mercy. Finally, sadly, it was time to leave. While the rest of the trip to Pisa, Lorenzana, Assisi, the Vatican and the rest of Rome was spectacular, nothing will compare with those days in Turin.

The Shroud remains at the Cathedral in Turin, but its next public viewing is not scheduled until the year 2035 (unless there is a special opportunity permitted as there was this time). I often get asked, “Why is the Shroud not always on public view?”

There are many answers to that question. Under law from the time of Christ’s death until really the Middle Ages, the mere thought of possessing or beholding the actual bloodstained burial cloth of Our Lord would have been repugnant. At the time of Christ’s death under Jewish law you were forbidden to posses burial cloths, and we know other contemporary societies in ancient times had similar customs. Early Christians probably knew the Shroud and other burial cloths (like the Sudarium of Oviedo in Spain) would be destroyed by early persecutors of the faith. The fact that pilgrims continue to come to Turin even when the Shroud is out of public view attests to its authenticity with the faithful. They cannot see it; they just want to be where the Holy Shroud is kept reverently.

As noted before, it will never be a requirement for those in the Catholic faith to accept that the Shroud is the true burial cloth of Jesus Christ. We know there was a linen cloth 2,000 years ago that was used to bury our Lord as He was laid in the tomb. Science has not been able to replicate this bloodstained shroud precisely or prove that it is not what it is purported to be.

After seeing the Shroud of Turin four times and spending nearly three hours in front of it, I carry a prayer card that I received in Turin. I read it each day after receiving the Eucharist at Mass. On one side is the photograph that Secondo Pia took in 1898 of the face of the Man in the Shroud. On the other side it concludes with these words, in Italian, “I know that there is no consolation without conversion, for that, with Your help, I will carry my crosses with trust, in a new life. I promise to begin removing myself from sin, and to be able to say that ‘from your scourges I was cured.’”

That is what I reflect on daily after seeing the Shroud of Turin. That I should not complain about what minor sufferings I think I may have to endure in my life. What we see on the Shroud of Turin, and know from the accounts of the Gospel, no man suffered more, for all of humanity, than God Himself.

Mark Armstrong can be reached through www.RaisingCatholicKids.com. He will be talking about this Catholic Lane article with EWTN’s Al Kresta on Friday May 20 from 4:00-4:25 PM ET and EWTN’s Teresa Tomeo on Monday May 23rd from 9:40-10 AM.

Highlights from the entire trip are posted here, http://gallery.me.com/markarmstrong2#100392

For excellent websites about the Shroud of Turin see:

- www.Sindone.org (the official website in Turin)

- www.Shroud.com

- www.ShroudofTurin.com

- www.ShroudStory.com