Movie Review: Resurrect Dead

Perhaps about five years ago I began to hear the word “random” with increasing frequency, usually from a teenager, and often as a one-word commentary on life’s apparent incongruities. FreeDictionary.com defines “random” as “a concept of non-order or non-coherence in a sequence of symbols or steps, such that there is no intelligible pattern or combination.” In my mind, this word sums up more than any other the Zeitgeist of the millennial generation. The world has become too complex and overwhelming: cause and effect are hard to determine. And who knows if anyone out there is listening? Who’s in control of this chaotic world?

Perhaps about five years ago I began to hear the word “random” with increasing frequency, usually from a teenager, and often as a one-word commentary on life’s apparent incongruities. FreeDictionary.com defines “random” as “a concept of non-order or non-coherence in a sequence of symbols or steps, such that there is no intelligible pattern or combination.” In my mind, this word sums up more than any other the Zeitgeist of the millennial generation. The world has become too complex and overwhelming: cause and effect are hard to determine. And who knows if anyone out there is listening? Who’s in control of this chaotic world?

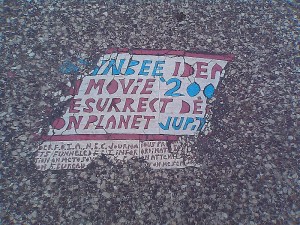

I kept thinking of this pervasive randomness and the desire for order and coherence while watching Resurrect Dead: the Mystery of the Toynbee Tiles. This film, which garnered Sundance honors for first-time director Jon Foy, draws our attention to a bizarre but little-noticed phenomenon: hundreds of tiles bearing this same cryptic message, found embedded in the asphalt of city streets as far apart as Philadelphia, St. Louis, and Santiago: “Toynbee Idea in Movie 2001. Resurrect Dead on Planet Jupiter.”

Foy’s documentary carefully reveals how young artist Justin Duerr became fascinated with the strange plaques and, with two other “Toynbee tile” enthusiasts, Steve Weinik and Colin Smith, spent years trying to discover the origin of the tiles and the meaning of the message contained in them. These men uncover increasingly bizarre clues: a newspaper article, a David Mamet play, a Jupiter colonization organization, and a Toynbee message that “hijacked” local news broadcasts. As a mystery, this film is a well-paced walk through the trial-and-error process of exploring possible leads, testing them, discarding the dead ends and pursuing the promising ones.

Yet, as Foy unobtrusively follows Duerr and Smith, it becomes clear that this film is more than an unorthodox urban whodunit. It is also an exploration of the human desire for connection. Justin Duerr has doggedly pursued this mystery for a decade. Foy says of Duerr, “When he hones in on something, he is 100% dedicated. He is just going at it to the exclusion of everything else.” Duerr believes one man is behind the Toynbee Tile message, and he is determined to not only discover his identity, but also to make contact. If he can find the messenger, he can understand the message and its importance.

As Duerr and Smith painstakingly dissect this esoteric ten-word cipher, we realize that it points to the possibility of physical resurrection, accomplished scientifically using human knowledge and skill. Of this message, Foy remarks, “There seems to be this possibility for magic in the world. And I feel like in the experience of getting older you lose a lot of that… I try to hold onto as much as I can. I feel like there’s dark, unexplored corners in the world where we can still believe in that synchronicity and we can still believe in these stranger-than-fiction kind of things.” Foy muses, “Some time in human civilization we’re going to find a way to stop dying.” When that time arrives, says Foy, humans will need to either stop reproducing or colonize space.

For the Christian filmgoer who is familiar with the biblical promise of resurrection, the idea of humans accomplishing such a feat through the use of scientific processes is indeed jarring. And yet, as far back as ancient Egyptian civilization, people have tried to overcome physical death and decay. Until the nineteenth century, however, this feat was universally acknowledged to require some sort of divine intervention. Paul’s explanation in 1 Corinthians 15 makes it clear that physical resurrection is part of the package deal that is the Kingdom of God: deliverance from the punishment, power and presence of sin, a new heart, a new mind, a new physical body on a new, radically remade earth. He wraps it up nicely in the letter to the Philippians: “Our citizenship is in heaven, from which also we eagerly wait for a Savior, the Lord Jesus Christ; who will transform the body of our humble state into conformity with the body of His glory, by the exertion of the power that He has even to subject all things to Himself.”

In Christian scholarship, there is a recent renewed interest in the resurrection of the body as an integral part of eternal life, rather than a blissful, disembodied immortality. “From Plato to Hegel and beyond, some of the greatest philosophers declared that what you think about death, and life beyond it, is the key to thinking seriously about everything else… This is something a Christian theologian should heartily endorse,” states N. T. Wright in his 2008 book, Surprised by Hope.

On yet another level, this film raises the philosophical question of how knowledge is gained. How do we know what we know? And how do we know what we know is true? Does truth stand on its own or is its legitimacy tied to its origin? Also, are the answers to the questions regarding the ultimate destiny of the human race understandable only by those who are smart enough or persistent enough to decipher messages from the intelligences beyond?

The Toynbee Tile message brings to mind the wildly popular book, The Da Vinci Code, which appeals to the Gnostic in all of us. Gnosticism reflects a desire to gain access to a secret knowledge that is available only to a few select people. It taps into a yearning to be one of the special people who can understand hidden knowledge over and against that which is revealed and available to all.

Is this film about the Toynbee tiles? About one outsider seeking to connect with another outsider? Or is it about the message on the tiles? In the end, this is a film about people trying to discover the truth about a person (or persons) trying to solve the problem of death.

Though the movie is short, Foy manages to pack a lot of information into those minutes. The film never drags and indeed sometimes goes a little too fast. Technically, the film has what the director calls a “lo-fi, kind of grainy look.” The music, an ambient and suspenseful score of Foy’s own composition, rolls in and out like a bank of fog on a dark highway. Foy has taken a complicated and enigmatic puzzle, organized it into a narrative and presented it in a 90-minute package that is accessible to almost anyone. I can imagine a parent or youth leader taking some young people to see Resurrect Dead at a small, independent theater and afterward discussing these issues over coffee. Millenials should understand that there really is a message for them, and in seeking the Messenger, they will discover not only a coherent worldview, but also a personal connection with their Creator, Who is anything but random.