Russia: Musings from The Motherland, Short on Mothers

I remember standing in my room in the Cosmos Hotel, sleep-deprived from airports and loaded down with equipment. The room may have once been handsome, but now its current condition is stale and threadbare — its blue carpet has thinned and its twin beds have sunken into visibly concave shapes. I turn the shower faucet, it spits yellow-tinged water.

I remember standing in my room in the Cosmos Hotel, sleep-deprived from airports and loaded down with equipment. The room may have once been handsome, but now its current condition is stale and threadbare — its blue carpet has thinned and its twin beds have sunken into visibly concave shapes. I turn the shower faucet, it spits yellow-tinged water.

Outside the room, a dim hallway arcs away from me, seemingly for miles. The Cosmos Hotel is old, but it was once magnificent, built for the Moscow Olympics in 1980 on an impressive scale. Walking through it, I have the odd sensation of floating unnaturally between two very different times: a gaudy, glitzy 1980 opening and a tired, businesslike present.

It would not be the last time I would have this feeling in Moscow.

To call Moscow a city of contradictions would be to risk sounding cliche, but if any city deserves the title, it is this one. From one of the Cosmos windows I can see the old All-Russian Exhibition Centre, situated in obsolete grandeur across the street. Built in the late 1930s and renovated in the 50s, the Centre was intended to be a monument to Soviet greatness, with wares from every bloc country displayed in huge, beautiful buildings. From the Cosmos, I can see the famous “Monument to the Conquerors of Space,” an impressive titanium obelisk with a steely rocket rocket astride the top. Further to the right, the gigantic gleaming figures of the Worker and Kolkhoz Woman stride forward with startling muscularity. Dimly in the distance, the Exhibition Centre’s “central pavilion” stands tall, its golden “steeple” shining brightly. Further back, out of sight, is the magnificent golden fountain.

But all it takes is an actual walk through the Exhibition Centre to peel back the glorious exterior. Since the fall of the Soviets, it has ceased being a monument to communism and is now … a mini-amusement park. The pavilions still stand, but a closer look reveals them to be unkempt, crumbling. The majestic fountain is now full of splashing teenagers, who climb its golden statues and lounge along the brink, listening to iPods. And the grand Central Pavilion — intended to be a monument to Soviet communism — is now a dingy flea market, where vendors hawk cameras, jewelry and gaudy wooden dolls.

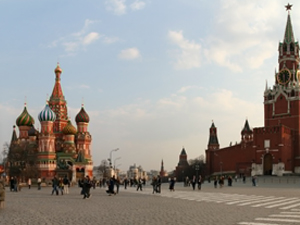

To me, that Exhibition Centre, as well as the moldering glory of the Cosmos Hotel, represented Moscow in a nutshell. Moscow is not a dead city, but it’s not a fully living one either, just like the country that it inhabits. It is a city that remembers and survives, but does not always press ahead. For instance, the KGB has been thrown from power, but its aging members still walk the streets, bullying passersby and setting up self-important checkpoints. The old Soviet monuments to communism have been abandoned, but only the thinnest tendrils of a free market have begun to overgrow them. Its murky, mysterious Orthodox churches are beautiful and full of ancient wonder, but their interiors grow steadily more empty, particularly of the younger generation. The streets are awash in new cars and people, but migration has brought them there, not a boom in Russian reproduction.

In short, Moscow, like Russia, needs to find itself again. And it needs to do that pretty soon.

Russia needs a demographic revival, but if that happens, it will merely be the result of a deeper cultural one. After spending so much time on the business end of some of the worst that the 20th century had to offer, Russia can definitely be forgiven for suffering from an advanced case of cultural malaise. The decaying Soviet monuments in the Exhibiton Centre are more than testaments to a fallen Communist empire, they are testaments to Russia’s damaged sense of identity.

But if Russia wants to escape the spiraling economic and social doldrums in which they find themselves now, that is going to take nothing short of a cultural revival. Once Russia finds its sense of purpose again, then it will find its legs.

We can only work in every way possible and pray that they manage to do that, before it’s too late.