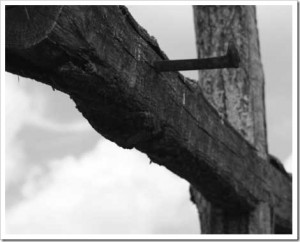

A Good Friday Devotion

When I was a kid my Mom used to embroider old sayings and decorate them with stitched designs and images. When they were finished she’d frame them and hang them on the walls, so that walking through our house was a little tour through the patrimony of wisdom from the ages, all arrayed in a splendor of rainbow hues. I didn’t think much about Mom’s “Threads of Wisdom” at the time, but even without knowing it, I was absorbing them into my bloodstream. Over the years I’ve been surprised at how those old sayings come unbidden to my mind at apropos moments, complete with visions of the needlework patterns and pictures. A favorite of my Mom’s was: “There are only two lasting bequests we can give our children, roots and wings.”

When I was a kid my Mom used to embroider old sayings and decorate them with stitched designs and images. When they were finished she’d frame them and hang them on the walls, so that walking through our house was a little tour through the patrimony of wisdom from the ages, all arrayed in a splendor of rainbow hues. I didn’t think much about Mom’s “Threads of Wisdom” at the time, but even without knowing it, I was absorbing them into my bloodstream. Over the years I’ve been surprised at how those old sayings come unbidden to my mind at apropos moments, complete with visions of the needlework patterns and pictures. A favorite of my Mom’s was: “There are only two lasting bequests we can give our children, roots and wings.”

One of the roots Mom and Dad cultivated for us kids was a simple Good Friday devotion. It was this: from noon to 3 P.M. on Good Friday we were not to eat, drink, or talk. Each of us children, and Mom and Dad also, were to go somewhere by ourselves and contemplate the Passion of Jesus Christ. We could take a Bible with us to read the Passion narrative if we wished (which I usually did). We could also take a Rosary and pray the sorrowful mysteries (which I usually did also).

I still remember those quiet afternoons of solitude and reflection. We each had our own special place where we usually spent our Good Friday observance. One of my brothers took the platform on the garage roof that Dad built to serve as our astronomical observatory. A sister took the scaffolding “tree house”: a section of left-over scaffolding Dad had made for some home repairs. When he finished the work on the house, he set up a section of the scaffolding under a tree in the backyard as a fort for us kids. It was just the right height to get you up in the branches with a leafy green canopy for a roof.

My spot was an old car Dad had salvaged and kept parked out back by the garage, just off the alley. I would sit on the hood of the car and use the windshield for a back rest as I read the Passion and prayed the Rosary and watched the clouds while thinking about the sacrifice of Jesus Christ.

Years later, after college and law school, I fell out of regular church attendance. Not that I ever made a conscious decision to quit going to church. It was just that starting my career I worked long hours, with lots of nights and weekends, and very little free time outside of work. When I wasn’t in the office, I was usually exhausted and I’d just crash. I’d order a huge slab of ribs, maybe a pizza or two, and gorge myself like a lion on the Serengeti bellying up to a fresh, steaming Wildebeest. Then, just like that lion after his big feed, I’d take my distended belly off to a nice, quiet place for a long sleep. Upon resurfacing into the world of consciousness, it was usually time to get the dry-cleaning, shine my shoes, and start it all over again.

And somewhere in that hectic cycle of work, dry-cleaning and shoe-shining, a lot of other things fell by the wayside, left behind like a bag of groceries forgotten at the check-out line. Too many distractions: cell phones ringing, errands to run, and already late for the next appointment. Life was busy, there was lots of noise, and somehow while my attention was diverted elsewhere, things slipped through the cracks. But then in the midst of the mayhem, Good Friday would come along, and that old family devotion always managed to cut through the clamor of the world. For three hours, rusty as I might be at spending time with God, I would fast and be silent and pray, and try to meditate on the Passion of Christ. Not that three hours of fasting is going to put you in the ascetic hall of fame, but some is better than none. Like G. K. Chesterton said, “If a thing is worth doing, it is worth doing badly.” Besides, compared to the zero hours dedicated over the rest of the twelve months, Good Friday represented a 300% increase for the year.

The little devotion started by Mom and Dad had the power to reach out to me decades later and bring me back to something I hadn’t even realized I’d forgotten. Homespun devotions have an importance explained in The Catechism of the Catholic Church:

At its core the piety of the people is a storehouse of values that offers answers of Christian wisdom to the great questions of life. The Catholic wisdom of the people is capable of fashioning a vital synthesis . . . It creatively combines the divine and the human, Christ and Mary, spirit and body, communion and institution, person and community, faith and homeland, intelligence and emotion. This wisdom is a Christian humanism that radically affirms the dignity of every person as a child of God, establishes a basic fraternity, teaches people to encounter nature and understand work, provides reasons for joy and humor even in the midst of a very hard life. CCC 1676

Traditions of the domestic church are bearers of the faith to the next generation. As Hilaire Belloc put it: “Now the Faith is not taught. It is inhabited and breathed in.” (The Essential Belloc, edited by McCloskey, Bloch, Robertson.) The faith is more lived than learned, more caught than taught, and it’s from our family – those with whom we inhabit and breath – that it’s most often caught.

Family devotions are a big part of that. Easter hams, candlelit evening Rosaries, religious pictures, reading out loud, crafts, statues of the saints, and seasonal carols all play their part in conveying different aspects of the great Faith that’s been gifted to us. The very tangibility of feasting and fasting, song and silence, light and dark, help the roots take hold. Smells and bells are important. In his book As I Lay Dying, Father Richard John Neuhaus said that we humans have “tactile” memory, embodied beings that we are, so that “even [our] thinking is sensuous. . . [our] recollections touching the burlap of disappointments and . . . the velvet of joys recalled.”

Father Barron wrote in Catholicism, the companion book to his movie series:

In the ancient world when a young man joined a philosophical school, say Plato’s academy, he was not simply enrolling in a series of classes or course of lectures in Platonic philosophy. He was signing on for an entire style of life, involving practices and bodily disciplines, as well as new patterns of thought. We find something very similar in the Acts of the Apostles, where the early Christian church is referred to as “the Way,” a term that catches this practical, embodied dimension of Catholic life.

A family is vastly more powerful than any philosophical school. Thus C. S. Lewis wrote in The Abolition of Man, “I had sooner play cards against a man who was quite skeptical about ethics, but bred to believe that ‘a gentleman does not cheat’, than against an irreproachable moral philosopher who had been brought up among sharpers.” Each family is its own “Way,” teaching all the time, whether we will it or no – perhaps more so at the times we aren’t at all conscious of teaching as at the times of intentional disquisition.

We all want to do something to change the world, especially these days. The good news is that we don’t have to launch a new philosophical movement to do it. Something far more powerful and effective has already been entrusted into our hands: our families. For those of us with children, we are changing the world every day in our role as parents. And even if we don’t have kids, we are sons and daughters, brothers and sisters, aunts and uncles, spiritual mothers and fathers, and a helping hand for those in need – and it’s all in the family, since we all have the same Father. To change the world, we don’t have to look any further than the dining room table. It was John Paul the Great said: “As the family goes, so the nation and so goes the whole world in which we live.” And that’s the kind of saying that used to be worthy of Mom’s needles and thread.