A Year Out: A Reflection on the “New” Translation of the Mass

The end of November, 2011 saw the one-year anniversary of the “new” translation of the Ordinary Form of the Roman Liturgy.

The end of November, 2011 saw the one-year anniversary of the “new” translation of the Ordinary Form of the Roman Liturgy.

Like many others, I welcomed the new translation. When I began hearing some of its texts, I heard a more dignified, elevated language that spoke more directly to the heavenly Mysteries the Liturgy purports to celebrate. Later, as I watched priests struggled with the texts (suddenly forced into the adage, “Say the black, do the red”) I was realistic about the situation but hoped for the best.

Within a couple of months after the translation’s promulgation, I observed priests continue some of their old habits with liturgical innovations. More sure of themselves, the eyes came away more often from the Missal, words not in the text were added and the ritual changed. I also heard what was either blatant heresy (or at the very least improper theology) preached from the pulpit. These things forced me to see more clearly the new translation is only a step and more work remains.

What exactly is this further work? In an article entitled “Quis ut Deus”, I pointed out the focus of religion is about the conversion of hearts, not in political processes. I believe the focus on the heart applies here as true liturgical renewal begins in the heart.

Jesus says it is not what goes into a man’s mouth that makes him unclean, but rather what comes out of it (Mt. 15:11). What comes out of a man’s mouth must originate from his heart. In liturgical studies, there is a concept known in Latin as the “ars celebrandi.” Simply speaking, this refers to the way in which the priest (or bishop) celebrates the sacred Liturgy. Does he take care with it or does he treat it in a slovenly manner? Do his actions point to or away from the sacred Mysteries?

Not a little rests upon the ars celebrandi as it reveals the thoughts (logismoi) of the celebrant’s heart and will affect deeply the congregation’s liturgical experience of God. Priestly formation therefore needs to cultivate an important attitude known as “sentire cum ecclesia” (to think with the Church). As the texts of the Mass themselves express the attitude and mind of the Church, it is therefore of tantamount importance to have a translation which reflects said attitude and mind.

Before I continue with the above train of thought, I would like to pause for a moment and make a few remarks on the language being translated, namely Latin.

Canon 249 of the 1983 Code of canon law states priestly formation programs must teach (provideatur) seminarians to know Latin well (“bene calleant”). The root of the verb “calleo” is “hardened” or “calloused.” The Code appears to indicate a vigorous study of Latin is required (not optional) for all seminarians. Why would the Code mandate such a study? The Second Vatican Council mandated it. The Decree on Priestly Training (Optatam Totius) says in paragraph 13:

Before beginning specifically ecclesiastical subjects, seminarians should be equipped with that humanistic and scientific training which young men in their own countries are wont to have as a foundation for higher studies. Moreover they are to acquire a knowledge of Latin which will enable them to understand and make use of the sources of so many sciences and of the documents of the Church. The study of the liturgical language proper to each rite should be considered necessary; a suitable knowledge of the languages of the Bible and of Tradition should be greatly encouraged.

It is my contention that within the tradition of the Latin Rite, Latin better disposes itself towards priests putting aside “human” considerations (such as their personality and/or abilities) and allowing them to focus on the sacred Mysteries. Concerning the vernacular, there is an inherent temptation: to sacrifice praying the Mass with reverence and attentiveness in favor of understanding the words. Sadly, this comes at the expense of and detriment to Mystery.

Note that in the above I say Latin “better disposes.” I do not say it is foolproof. The real issue at hand is the interior disposition of the priest towards the sacred Mysteries, his reverence and attentiveness. In the vernacular, if a priest flies through the language, he is still somewhat intelligible. However, any inattentiveness and irreverence can be glossed-over by appealing to the fact the people can understand the language. The above cannot be said for Latin as it forces a priest to take time with the text of the Liturgy.

While Latin may force a priest to take time with the text of the Liturgy, it, too, is not foolproof as priests could rattle through the Latin. Once again, the real issue is the interior disposition of the priest towards the sacred Mysteries. Therefore, I see the matter of Latin and the Liturgy presenting two different directions. The first direction is using Latin as a “teaching moment” that can greatly assist inculcating a sense of the sacred within the priest. The second direction is simply to give up, thinking it is too hard and the priest will “never get it.” This is the easiest of the directions and, sadly, one I suspect not a few have taken.

The above being said, I will now return to my previous discussion on the “new” translation of the Ordinary Form.

If the “new” translation of the Mass is to have any sort of credibility and impact, it must be faithful to the mind of the Church. That mind is intimately associated with the Latin language and culture. Therefore, it does not surprise me to hear of people clamoring over the “new” translation as it is much more faithful to the Latin mind, culture and theology.

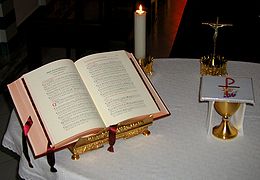

I cannot help but wonder at those who clamor for the above. It seems to me they want a more “pure” English translation. “Pure” here means a translation stripped of any vestiges of the Latin culture. One particular criticism I have noted consistently is a complaint over the word “chalice” for the Greek word “poterion,” formerly translated as “cup.” I need not discuss the linguistic arguments concerning the word “chalice.” Such arguments distract from the actual point upon which we need to focus: proper reverence to the Blessed Sacrament.

In a famous essay published in 1966, Dietrich von Hildebrand spoke about the concept of reverence in Mass. In this essay, he reminds us the “most elementary gesture of reverence is a response to being itself.” As basic Catholic philosophy and theology teaches, there is no higher Being than God Himself and after the act of Transubstantiation, Christ is present in the Sacred Species. It is highly irreverent, to say nothing of being disrespectful, to the Author of all Being by putting His Body and Blood in anything unworthy or unbecoming of the Divine Majesty.

Nevertheless, it was precisely the above attitude that caught on in the euphoria of the 1960s. God was now “one of us” but not in the same sense used by St. Paul or in 1900 years of Christian theology of the Incarnation. In the new understanding, God was hurled-down from the heights in order to subject Him to the whims of prideful humanity, which sought to place itself at the center of all things. Original sin was forgotten and a progressive humanism prevailed, one in which God now played second-fiddle to “community” which, by the way, was now “Eucharist.”[i]

It comes as no surprise to me when I hear clamoring over the new word “chalice” instead of “cup.” The very word “chalice” does carry in American English the imagery of an ornate object as opposed to a more simple one conveyed by “cup.” I suspect this connotation is carried over from the days when Latin culture prevailed in western civilization, a culture inherently affected by Catholic theology with its understanding of Transubstantiation and the philosophy of being.

Thus the true fight facing us is not the translation of the Mass. That is only a sign and symptom of a much larger reality. What we are fighting is a war for the very soul of the West.

[i] The forgetting of Original Sin seems to be tacitly referred to by Pope Benedict XVI in October, 2012.