Archbishop Romero and Me

I barely met Archbishop Oscar Romero. As in the old Ben-Hur movies, where the heroes have a chance encounter with Jesus Christ in a melodramatic scene that has little to do with the plot of the movie, I brushed up against Monseñor in brief and transient episodes in my childhood. But someday, if God permits me, I will attest to generations who never saw him, that I did see him, even if I barely managed to do so.

Our coincidence in this “vale of tears” was a blink of an eye. When I was born in 1968, Monseñor had just over eleven years left of his pilgrimage through this earth. And when he became Archbishop of San Salvador, which was the first time he registered in my awareness, I only had year and a half left in the country. But he made a great impact, right from the start.

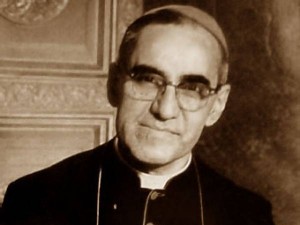

I vividly remember the first time I saw his picture, in black and white, in “El Diario De Hoy” (a Salvadoran paper) in 1977, when he was named Archbishop of San Salvador. I read the interview, and I followed his first dramatic steps on the radio, hearing his impressive Sunday homilies, along with the rest of the country. My grandmother who raised me would take me to cathedral for the most important dates in the liturgical calendar, such as Christmas, Easter, and the Feast of the Transfiguration to see the “Savior of the World” (Jesus, El Salvador’s patron).

It was in this context that witnessed his prophetic ministry in the culminating moments of his public ministry. It was in 1977 that they killed Father Rutilio Grande, and Father Alfonso Navarro a few months later. I remember going to the Cathedral on Holy Saturday one year and watching a Boy Scouts bonfire in Plaza Barrios in front of the church. I remember watching Romero and some of his priests in a procession around the inside of the cathedral, perfuming the temple with incense and sprinkling holy water while the congregation sang, “The Lord is risen/Risen is the Lord.” I remember seeing trucks full of soldiers around the square and thinking they were there to participate in the Mass, perhaps providing protection to the flock of the faithful. It never occurred to me in my nine years of age that their presence could be more sinister.

But my dearest and most sacrosanct memories of Archbishop Romero were more intimate encounters, although they were all passing moments. Three episodes take precedence over all others, and are etched in my memory forever.

Once Archbishop Romero entered, without advance notice, a Mass I attended with my grandmother in the now-disappeared Church of San Esteban (St. Stephen’s), in the district of the same name (this temple was consumed by fire in January 2013). Since the Mass had begun, he was announced by bullhorn from the back of the church, where as I remember, he was delivered by car.

He walked down the main aisle of the church, with a green chasuble and his bishop’s miter, blessing and greeting those present, and passing directly in front of me. For a moment, we saw eye-to-eye. Although it was over in a flash, it made a lasting impression because St. Stephen was the first martyr of Christianity. To me it was like a sign and a blessing to have lived this coincidence.

On another occasion, my grandmother and I had attended Mass at the Cathedral, and upon exiting the church we saw that Archbishop Romero was greeting people on the front steps, before Plaza Barrios. Taking advantage of a small opening in the crowds around him, at a moment when there was no one there, my grandmother came to him and knelt before him to kiss his ring. He crowned her with his pontifical blessing.

Being a little shy, I did not come too close, preferring to appreciate this beatific image from the sidelines. For me, my grandmother and Romero have been my spiritual parents, and this image figures for me like a family portrait.

The third meeting is the most intimate, but in some ways, the most ineffable and elusive one. We were again at the Cathedral, possibly the same Holy Saturday discussed before. I walked into a confessional. The details are blurry, a mystery that melts into the mysticism and spirituality of the moment to make that episode into something beyond history and time. Yet upon hearing that unmistakable voice, I was left with the undeniable certainty that Archbishop Romero was my confessor!

I remember being struck by the lack of formality of his questions, and the lack of austerity in his style of addressing me. Instead of reciting the repetitive phrases of a formal confession, he asked me what parish I was from, and other things that were not strictly part of an obligatory or customary examination of conscience. Although I was sure that it was him, I take a certain delight in being able to doubt if it really was—because it adds to the mystique of the moment, and to the supernatural persistence of his presence in our lives.

Archbishop Romero was a spiritual being whose presence in history cannot be accounted for with the sterile rules of science, or political science, or social theology. He was a spiritual force, like the shadow of God hovering over the land.

I do not want to pretend that these episodes were anything other than casual encounters: ephemeral and passing. It truly is very likely that Archbishop Romero did not notice me. Indeed, my goal in recounting them is to say that I noticed him. By a happy accident of history, I have brushed up against this historical figure, and the grace of bearing witness to his existence challenges me to also bear witness to his cause.