Castellani’s Eyeglasses

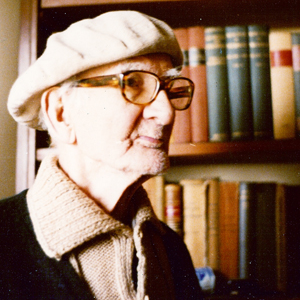

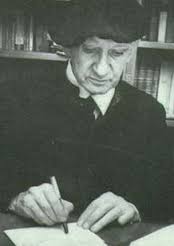

I have a dear friend in Buenos Aires, Fabián Rodríguez Simón, a voracious reader and recalcitrant freethinker. Every time we meet I like to engage with him in tough (and bitter) theological disputes. In one occasion, while reviewing the great Catholic writers of the 20th century, from Chesterton to Lewis, from Bloy to Tolkien, my friend enriched the list with the name of one of his countrymen that was completely unknown to me: Leonardo Castellani. Please consider that I believe myself to be a connoisseur of Argentine literature — I confessed I had never heard of that Castellani — and my friend, after feigning amazement at my ignorance and making some fun of me, unearthed a few of his books from the chaotic shelves of his personal library. I will never thank him enough: Leonardo Castellani (Argentine, born 1899 in Santa Fe, died in 1981 in Buenos Aires) was a writer of extraordinary vigor, equally gifted for diatribe and sententious thought, satire, and biblical exegesis. With a style that springs from Cervantes and meanders like a torrent through all kinds of genre: novel and essay, poetry and literary critique, detective stories, and newspaper articles. Passionate polemicist, formidable critic of modernity, poet with a harsh prophetic streak; prophet with a lyrical trance. Castellani is above all a champion of orthodoxy, the only possible form of heterodoxy in this age.

I enjoyed reading Castellani a whole lot and hope to continue doing so for a long time because finding some of his books has nearly turned into detective work after his oeuvre was relegated to dusty corners by slothful publishers. In my life as a reader I had my share of being swept off my feet but never with such enormous force, when one compares that to the scarce recognition received by the author. Castellani distinguished himself for reaffirming – and never retreat from – those aesthetic, philosophical, or religious positions that the bull delivery- boys of the intellectual mob have declared anathema. That feral vocation of singular individuality earned him an exile to the outskirts of discredit where the modern censure of the politically correct buries those who have the guts to be relentless contrarians. Truth be honored that death sentence is not much different from the punishments he endured while being alive: expelled from the Society of Jesus, Castellani suffered all kind of iniquities and abuse until he died old and ailing finding refuge only in his untamed faith and a fierce loyalty to his two vocations, intimately related: that of a priest and a writer.

A few days ago, invited by the Colegio San Pablo of Madrid, I spoke to a young audience of the joyous discovery of Castellani’s opus. I found out then, with a mix of surprise and jubilation, that among the audience were some Argentines sharing my devotion for that quixotic brigand of a priest. Both were sons of disciples of Castellani, men that had shared the tribulations of their teacher and walked with him the long years of affliction (that lasted for most of his life) when he could hardly find anyone who would print his books. One of those young men, Mariano Jora, confided to me that in his room he kept like a relic the worn out eyeglasses that Leonardo Castellani donned in his last days, before he closed his eyes forever; before he open them to contemplate the only Glory he pursued in his life. With a mix of inner trembling and overwhelming joy I begged Mariano to please show me that treasure and he rushed to his room to fetch them. They were eyeglasses mounted on a cheap frame, so destitute that seemed to me like they were barely attached to those loose temples held together with some crummy old cellophane tape. Those were the eyeglasses of a man that walked the tightrope of pure survival, a man that had no money for new spectacles, someone who gave not even a thought to getting new glasses because he had made of poverty his home, his sustenance, his consolation, his dignity, his most intimate substance.

I contemplated them for quite a while, moved by emotion, almost as if they contained a painful moral teaching. And I thought that those almost miserable eyeglasses were the witness of a life of deprivation and ill fortune but they were as well a metaphor of a shortsighted age, too immersed in fashion and camp vanity, that wears out its best men without even noticing them. The work of Leonardo Castellani had to be inevitably rediscovered. If only one of you reading this article goes in search of his books and starts reading piqued by curiosity, I will be the happiest man on earth.

Originally translated by Carlos Caso-Rosendi in Delumen. Published by CL on Castellani’s 115th birthday.