Catholic Politics

The cardinal looked grim. “This is the situation now,” he said. “One political party is dangerous and the other is stupid.”

The cardinal looked grim. “This is the situation now,” he said. “One political party is dangerous and the other is stupid.”

Since that was said in a private chat, it wouldn’t be fair for me to name the speaker. But his comment expresses sentiments that probably are widely shared in the American hierarchy today, as indeed they’re shared widely by many Americans. Bipartisan disgust with politics is a sorry byproduct of our recent, toxic election campaign. If the country should actually topple over the infamous fiscal cliff, plenty of people would suppose both parties gave it a shove.

The cardinal’s words also have considerable relevance for the Church, underlining something that’s now more clear than ever. While the Church is obliged to take both deeply flawed political coalitions as facts, it has no natural home in either.

No cause for smugness here, though. Before lecturing the parties, the Church needs to face up to internal problems of its own, which requires recognizing what those problems are.

The National Catholic Reporter, viewing reality through the lenses of left-wing Catholicism, accuses bishops who spoke out strongly during the campaign of “alienating” all but a “small choir” of the faithful who agree with them on issues.

Maybe so. But maybe it’s just the Reporter and its friends who are alienated. Washington Post columnist Michael Gerson gets closer to the truth when he notes that, while 50% of Catholics overall voted for Barack Obama, the seven-point shift away from Obama among white Catholics from 2008 to 2012 was “one of the largest swings of any portion of the electorate.” In a close election, he adds, it could have determined the outcome.

The point isn’t that Catholic voting directly mirrors what bishops say. But at least the outspokenness of some bishops seems not to have had the widespread alienating effect the Catholic Reporter likes to think it had. Still, leaving aside the parsing of the Catholic vote, it’s obvious that many American Catholics just aren’t hearing—or anyway heeding—the Church’s message on the relationship of doctrine to politics and the rest of life.

At their fall assembly in November, the bishops approved a document on preaching that makes the familiar point that a typical congregation today includes a lot of people who are “inadequately catechized.” Here is a delicate way of saying even many who go to Mass don’t have a clear notion of what the Church teaches and don’t see how it applies to them. That has deeply negative implications for political behavior and nearly everything else.

If Catholic teaching matters, this needs to change. The bishops should give early attention to a massive, continuing, and intellectually serious program—one not directly tied to politics and the election cycle—to educate Catholics in the doctrine of their Church, including social doctrine and doctrine on human life and marriage. Isolated statements in the face of election year passions aren’t enough.

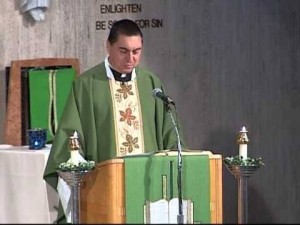

Homilies should be a part of this new effort but only part. Ongoing adult education is essential. And the Church must reach out through the use of new and old media to the dismayingly large number of Catholics who seldom attend Mass.

During the Baltimore assembly, the bishops voted to create a new public affairs unit in their national conference. It would do well to make this effort a high priority. Then maybe all those newly well-informed Catholics would begin working for the reform of American politics and the renewal of the social order.

I can dream, can’t I?