Collecting the Debt to Society

Repeatedly, the US Catholic Bishops have issued their plaintive calls, asking us to fix our “broken and destructive” criminal justice system here in America. Most of us paid this call no attention at all. Perhaps this was to be expected; I’m afraid the USCCB’s recommendations have not always been free from a certain tincture of worldly wisdom and many of us have trained ourselves to take their trendier pronouncements with a grain of salt. This one, however, comes straight from the heart of the Gospel, straight from that great Prison Reformer who, on Judgment Day, will chide the condemned in these words: “I was a stranger and you did not welcome me, naked and you did not clothe me, sick and in prison and you did not visit me.” (Mt 25:53). Let’s all take a moment or two, then, to reflect upon how meaningful Christian prison reform might actually be accomplished here in 21st century America.

Repeatedly, the US Catholic Bishops have issued their plaintive calls, asking us to fix our “broken and destructive” criminal justice system here in America. Most of us paid this call no attention at all. Perhaps this was to be expected; I’m afraid the USCCB’s recommendations have not always been free from a certain tincture of worldly wisdom and many of us have trained ourselves to take their trendier pronouncements with a grain of salt. This one, however, comes straight from the heart of the Gospel, straight from that great Prison Reformer who, on Judgment Day, will chide the condemned in these words: “I was a stranger and you did not welcome me, naked and you did not clothe me, sick and in prison and you did not visit me.” (Mt 25:53). Let’s all take a moment or two, then, to reflect upon how meaningful Christian prison reform might actually be accomplished here in 21st century America.

First of all, let’s concur that just tinkering with the existing mess won’t do. What we’re dealing with here is such a complete and total breakdown, such a ghastly human train wreck, that anything less than a strong urge to go immediately back to the drawing board reflects ignorance of the situation. What’s going on now is simply a nightmare in the daylight. Our country owns nothing less than the highest per capita number of incarcerated persons on the planet. If every man, woman, and child living in an American prison right now were gathered up in one place, you’d have a metropolitan area the size of Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

And make no mistake—once they’re in, they’re in to stay. Less than fourteen percent of these people, once released, will ever succeed in becoming “useful members of society” again; they’ll either go back into prison later or be added to the welfare roles as “unemployable” ex-cons. Either way, they’ve become permanent wards of the state. Rehabilitation is a fairy tale—and, sadly, it’s a storybook ending that most Americans don’t even want for these people anymore. What do we want, then? I’m afraid most of us just want them to go away—either via the death penalty or into our ever-growing and ill-funded chain of ramshackle prisons.

Yet it’s at just this point in our musings that we begin to get an intriguing glimpse of the philosophical dead-end that produced the tragedy…and a possible way out.

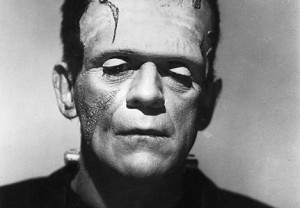

Remember the old Boris Karloff classic Frankenstein? In that film, the mad doctor’s experiment goes awry because his hunchbacked assistant has stolen the wrong brain for his creation—not a healthy, normal brain but a brain from a different jar, a jar marked “abnormal,” the brain, we are told, of a criminal. This is why Frankenstein’s monster has turned out to be such a brute—because there’s something wrong inside his head, because he has (almost literally) a screw loose someplace. His criminality is hard wired, so to speak—built in at the factory—and we can see that he’s a lost cause right from the start.

Well, is there, in real life, any such thing as “the criminal brain”?

Not according to the teachings of the Catholic Church. The Church teaches that criminality resides in the soul, not in the body; and it’s we ourselves who make these evil choices, not some defective organ hidden within. Of course, there are people who do suffer from mental illnesses of one kind or another, illnesses that do cause them to lose control in anti-social ways. But if they’ve truly lost control then they aren’t really criminals in the Christian sense of the word. A man literally out of his senses can’t be blamed for what he does, any more than a motorist can be blamed for wrecking his car if the steering wheel comes off in his hands. No, true criminality enters the equation only when free, self-determining souls under God, who know right from wrong, freely choose to do the one and not the other. This state, theologically speaking, is known as sinfulness, and the condition that created its worldwide prevalence is known as original sin. Ever since Adam’s fall we all know that downward pull, we all experience temptation and then—when we fail to resist it—actual guilt. So in that sense, we’re all like Frankenstein’s monster. We all got the “criminal brain.”

And since criminality is spiritual, the Church’s remedies for it are likewise spiritual. In countries where the Catholic worldview has dominated, prisons haven’t been called “correctional facilities” (i.e., places to repair a broken machine) but penitentiaries…a place for penitents where the object, of course, was penance. These were places where the guilty soul could expiate its crimes on earth, where the criminal could work off what was known (in a very valuable phrase) as “his debt to society.” And once the debt was paid, the debtor was forgiven. The slate was wiped clean and absolution was dispensed.

But there never can be any absolution for a criminal brain. All we can hope to do in that universe is to segregate those who got one, and keep them safely away from us lucky folks who got theirs out of the other jar.

How did this mechanistic, sub-Christian outlook become so pervasive in America? Much of it, I think, can be traced to our nation’s Calvinistic cultural background. Calvinism holds that God chose, from the foundation of the world, which human souls would be elect and which would be reprobate. Thus, a man’s sins can’t really be said to damn his soul so much as they reveal his soul to have been damned all along. Most of these American Calvinists gradually evolved, over the 18th and 19th centuries, first into Unitarians, and then finally into freethinkers and atheists. But this strong sense of determinism has clung to their outlook to this very day. In the Calvinist scheme (whether religious or secular) a man does society a favor by committing a crime and getting caught. He has let the cat out of the bag. He’s revealed himself as one of the broken ones, as a man with a criminal brain, capable of criminal acts—not like the rest of us. And now he can be safely herded into the national holding pen where he won’t be able to hurt anyone any more.

It seems to me then, that the solution to our prison problem lies in a renunciation of heresy. We need to stop thinking of criminals as a tribe apart, but as sinners like ourselves. Period. And what do these, our fellow sinners, need? They need to be offered penance, a chance to pay their debt to society. What we are currently offering them instead is the mark of Cain on their foreheads and Hester Prynne’s Scarlet Letter on their breasts.

Even if a person does manage to get out of one of our “correctional facilities” without becoming a victim of homosexual rape, a certifiable basket case, or a trained professional miscreant, we have already pronounced a life sentence on them. What do I mean? I mean that these people will carry a criminal record with them forever. The debt, in other words, can never really be paid, and the slate is never wiped clean; it’s too important to warn the “normal people” about their criminal brains. In a word, we have removed any effective possibility of restoration…and in response, our “penitentiaries” have become sinks of despair.

If, on the contrary, we were to bring back the concept of restoration in our system—by eliminating criminal records (except in the case of true psychological compulsions like serial rape or child molestation)—then our prisons could become penitentiaries again. We could begin collecting the debt to society, through work programs, vocational training, church attendance, personal development, and education. Rather than assigning prison terms in arbitrary numbers of years (years to be spent sitting around smoking and watching Jerry Springer) we might assign sentences in terms of debt to be paid—debts that might be worked off more quickly through industry and initiative, less quickly through sloth and insubordination. And the sooner the debt is paid, the sooner the absolution (which must be total) can be given.

Of course, the exact details of such a proposal would have to be carefully worked out by wise statesmen and orthodox thinkers, on the basis of what people are now calling “tough love.” Business, in particular, would have to be weaned off some of their addiction to government money. That way, part of what society now pays contractors to do could be accomplished instead by those who already owe society this debt we’ve been talking about. There would be other difficult paradigm shifts as well. But the effort, I believe, would be well worth making.

One thing is for certain. We must never forget, even in the name of “law and order”, the great prayer Jesus taught in His Sermon on the Mount: “…forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive those who trespass against us…For if you forgive men their trespasses, your heavenly Father also will forgive you; but if you do not forgive men their trespasses, neither will your Father forgive your trespasses.” [Mt 6:14-15].

After all, Christ himself spent the night in jail once.