Constantine and Christendom: Glory or Calamity?

God did not send the Savior to a pacifist society in Nepal, or to some remote place eschewing military preparedness (like an ancient version of today’s Costa Rica). Instead he chose the world’s greatest and most literate empire at “the fullness of time.”[1]

God did not send the Savior to a pacifist society in Nepal, or to some remote place eschewing military preparedness (like an ancient version of today’s Costa Rica). Instead he chose the world’s greatest and most literate empire at “the fullness of time.”[1]

The Pax Romana, the Roman Peace, was maintained by training, equipping and deploying scores of legions to fight on the frontiers and keep order within the Empire. Imperial Rome was very much about political authority over society, in conjunction with a readiness to wield the power of the sword described in Romans 13:4.

Yet much of this legacy was hard for the Church to embrace. When for 2½ centuries the sword of state was turned against us; when Emperors so frequently reversed St. Paul’s axiom that government existed to punish evildoers and reinforce the good; then God provided Christians with various avenues of escape. They ranged from going over to the Goths and fleeing imperial domains; or finding refuge in “fields and deserts, forests and mountains;” or to the ultimate escape, i.e. graduating to a better world via the course of martyrdom.

Under Constantine we went from being persecuted to enjoying preeminence. At first, Christians found it hard to adjust to this radical transformation. In the end they found it impossible to discern the divine will without reference to salvation history. Our ancestors in the Faith had to take divine Providence as it actually transpired, not as one might suppose the Great Helmsman of history could more fortuitously have steered the course of events.

Proud minds ready to second-guess God wonder why the Divinity did not stop Christians from having recourse to the sword; or why God let the Church be sullied by immersion in power politics. Such thinking overlooks Isaiah 55:9: “For as the heavens are exalted above the earth, so are my ways exalted above your ways, and my thoughts above your thoughts.” Only in that context can we understand the ways of Divine Providence. Otherwise it is incomprehensible that from the days of Pontius Pilate until Diocletian and Galerius the Beast, we suffered upon the cross of persecution. And then, during the dominion of Christendom, the not infrequent burden for believers was to labor under the hypocrisy of ostensibly Catholic rulers.

And so we went from tyrants who persecuted us, to rulers who deceived us. How could such a mix of misfortunes have come to pass? I would argue that it was inherent in fallen humanity’s condition, and intrinsic to God’s plan of salvation.

Christ founded Christianity, and his loyal servant, Constantine, founded Christendom. Unlike Christianity, however, Christendom was both in the world and of the world. Ipso facto vanity was present from the outset.

The Epistle to the Romans puts it thus, “For creation was made subject to vanity – not by its own will but by reason of him who made it subject.” (Romans 8:20) St. Paul goes on to explain how all creation groans and travails in pain, but with the hope of eventual delivery from the slavery to the vain things of this world. One of the worst of vanities is a man’s refusal to believe Divine revelation. “For God has locked up all in the prison of unbelief, that upon all alike He may have mercy.” (Romans 11:32) So too with other manifestations of vanity, like lust for political status and power.

It is no surprise, then, that the pain of subjection to vanity takes different forms depending on whether Christians experience direct persecution from pagan rulers; or as in the halcyon days of Constantine, when the merciful God comes to our rescue, scatters the proud in the conceit of their hearts, and puts down the mighty from their thrones (Luke 1:51-52). Yet, whether in good times or bad, the world must endure an overarching oppression by vanity.

Vain craving for status created dissension within, of all places, the sacred ranks of the Apostles. But Jesus reprimanded them for trying to lord it over others, and he urged them to follow his example. “I came not to be served, but to serve” (Mark 10: 42-45). Thus did Jesus wash his Apostles’ feet at the Last Supper.

If the curse of vanity could afflict even the college of the Apostles, then pray tell what institution consisting of mere mortals could escape it? Wisdom must respond, “none will escape.”

Therefore, the view popularized in the 17th century that the revolution under Constantine was what first introduced corruption into the Church is, as T.G. Elliott put it, a “dream.” According to Professor Elliott this illusion led to the delusion “that Constantine corrupted a Church which was glorying in its pristine virtue by making it into a servant of the state.”[2]

On the contrary, Constantine, the devout Catholic, would hardly have entertained a desire to make the Church into a footstool of his throne.[3] Not all of his successors were so pious or reticent, however, and church-state rivalries reared their head from time to time throughout the many centuries when the terms “Western Civilization” and “Christendom” were synonymous.

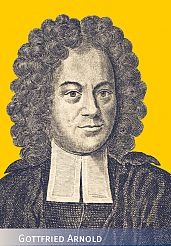

But the Pietistic-Lutheran condemnation of Constantine – eventually articulated in scholarly fashion by Gottfried Arnold (c. 1699) – saw ‘religious decadence’ in a ‘fall’ or ‘estrangement’ from original Christian purity.[4] In idealizing primitive Christianity during the persecution, Arnold apparently forgot the pervasive curse of vanity which creeps into every human institution. It is in this context that the limitations inherent in the most salutary reforms must be kept in perspective, including even that revolution par excellence, as pushed through under the leadership of Constantine.

Mark 9:1 suggests, somewhat mysteriously, that the Lord intended to see his kingdom “coming in power,” sooner or later.[5] Which is quite the contrary of a weak Church vulnerable throughout history to every hostile confrontation. It is wishful thinking to suppose that if the Church had eschewed political power and militarism in the 4th century, the forces of darkness would not have discovered a host of other ways to create discord and hypocrisy in ecclesiastical leadership.

Mark 9:1 suggests, somewhat mysteriously, that the Lord intended to see his kingdom “coming in power,” sooner or later.[5] Which is quite the contrary of a weak Church vulnerable throughout history to every hostile confrontation. It is wishful thinking to suppose that if the Church had eschewed political power and militarism in the 4th century, the forces of darkness would not have discovered a host of other ways to create discord and hypocrisy in ecclesiastical leadership.

Overlooking Martin Luther’s dictum, “wherever God builds a church, the Devil will build a chapel hard by,” Arnold remained steadfast in refusing to see the merits and advantages of the Christian revolution under Constantine. Nor would Arnold and his followers acknowledge manifest interpositions of Providence, and so take salvation history into account theologically.

Arnold anticipated the even more radical founder of Mormonism, Joseph Smith, who thought Christ’s prophesy was in error (Matthew 16:18), insofar as the gates of hell did allegedly prevail against the Church for some fifty generations, until the advent of the Latter Day Saints in the first third of the 19th century.

_____

The flip side of downfalls that derived from imperial Roman roots is more interesting to secularists. Historians of irreligious or of non-religious bent are naturally less worried about how the Church gets corrupted, than about how religion might corrupt the state. Those who think the later Roman Empire in the West was worthy of preservation were appalled by its fall. For many centuries they have cast around for a scapegoat. Political and economic explanations have abounded. But some historians have sought a cultural cause, and of their number some have settled on Christianity as the culprit. Plausibly they have argued that going over to the Gospel weakened Rome by severing the Empire from its cultural roots in pagan myth.[6]

Others have contended that Christianity’s insistence on charity was unmanly. It softened the Romans and made them wimpy prey for barbarian invaders. But among the leading secular historians who examined the fall of Rome was Jacob Burckhardt, whose Age of Constantine (1853) sees “’a clear testimony of the senility and decadence of Roman life, for which no blame is to be attached to Christianity.’”[7]

My view is that the muscular Christianity of Constantine bolstered the Empire. Otherwise it would have collapsed a century earlier than it did in the West. And in the East, moving the capitol to Constantinople converted the Empire into a downsized and defensible fortress. The latter proved to be the most stable and long-enduring Christian Empire in the annals of history.[8]

The imperial period from Constantine to Theodosius has been compared to the Old Testament era from Moses to King David – deliverance from slavery under Moses to theocratic dominion under David.[9] Constantine reasserted the political dimension in salvation history – more like the Maccabean revolution, really, than the Exodus. Also he squelched the pacifism that had characterized clerical leadership since the Apostle Peter sheathed his sword in the Garden of Olives.

In his self-described role as “general bishop,”[10] Constantine was not only mediating between church and state, but also militarizing believers. At his behest the council of Arles for the Western Church (August 314) rescinded the strictures against serving as a soldier in the Roman army. Canon 3 gave ecclesiastical sanction to military service, and even threatened Catholics with excommunication “‘who threw down their arms in time of peace.’”[11]

Yet to this day the Church is not very comfortable with the concept of armed insurrection as practiced by Christians in 312 under Constantine’s leadership. The Church commissioned by Pius X for construction on Milvian Square, Rome, later named the Church of the Great Mother of God, was not built until 1931; and was refocused on what was then the 15th centennial of the Council of Ephesus.

A tendency which we might term quasi-pacifist may help to explain why so many Church histories lead us to believe that the Christian response to Rome’s campaign of persecution fell neatly into three forms. Notwithstanding the turbulent milieu of the 3rd and early 4th century Empire, the tripartite view is emphatic that Christians (1) fled, or (2) gave in under the pressure of torture, or (3) heroically embraced martyrdom like lambs led to the slaughter.

Are we really to think that the 4th response, violent resistance, was anathema to all Roman citizens who were Christian? Or that recourse to the sword – which St. Thomas Aquinas would later approve on condition it be out of zeal for justice, under God [12] – was unthinkable to our brothers and sisters in the faith prior to 312? It seems more likely that revolutionaries were indeed active in places, but “standing in the shadows” like the Zealots of Jesus’ time – the faction to which the Apostle, Simon the Zealot, belonged.[13]

Catholic ambivalence about acknowledging and celebrating Christian militarism has notable exceptions. Three battles have been observed officially by the Church in connection with the Rosary, including most notably the great naval victory at Lepanto in 1571, commemorated today as the Feast of Our Lady of the Rosary.[14]

But exceptions neither explain nor refute the preferential option for pacifism. Looking back, the Crusades to the Holy Land do not exactly generate enthusiasm. Furthermore, during the crisis in the garden of olives, our divine Leader, the Prince of Peace, told St. Peter to put his sword back into the scabbard after he had severed the ear of Malchus. “He who lives by the sword,” Jesus stated, “will die by the sword.”

Nonetheless, only hours before, the Gospel informs us that Peter’s sword and a second one were in the possession of the Apostles in the upper room during the Last Supper. Far from ordering them to discard both swords, or sell them and give the proceeds to the poor, Jesus indicated simply that two swords were sufficient. “Enough,” said he. (Luke 22: 36-38).

And yet the editorial explanation footnoted to my Bible wants to downplay the possession of swords by the Apostles. The editor writing the gloss spins the two swords as references to spiritual conflict: “The Apostles must be prepared through spiritual weapons to meet all sorts of dangers, trials and hardships.”[15] Well, yes, true enough on the allegorical level. But this biblical verse bears witness to an apostolic reality, not solely to allegory.

Since the Revolution of 1989 in Eastern Europe, which began in Poland, Pope John Paul commissioned the first official Catechism of the Catholic Church since the 16th century. Approved by JP II in 1994, the Catechism includes a section (2243) which authorizes armed resistance to oppression by one’s government under certain conditions. Still, during the Arab Spring Pope Benedict XVI refrained from any sort of blessing for the armed uprisings against oppressive dictators. And during the Spanish Civil War, 1936-39, when 6832 priests and religious were martyred for the faith, including 13 bishops; Pope Pius XI did not officially take sides until the Summer of 1937, more than a year after the outbreak of The Last Crusade.[16]

Others might cite President Lincoln’s 2nd inaugural address during the U.S. Civil War as an example of the potentially bloody nature of civil conflict necessary to purge a great evil from society (slavery in that case).

Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said ‘the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.’

How, then, are we to evaluate Constantine for his soldierly influence on our religion? Double thumbs-up is surely indicated; given that without Constantine’s militarization of Christendom, it is hard to see how Christianity could have prospered so remarkably during the barbarism of the Dark Ages. Nor would it have exercised such a significant civilizing influence.

It must be conceded, however, that militarizing Christianity as well as immersing the Church in politics would open the gates to trouble. But Christ never promised that the history of the Christianity down through the centuries would be trouble free; nor that the angels would keep wolves from infiltrating our ranks.

He did assure us that the gates of hell would not prevail against the Church as a whole. And he fulfilled that promise for several centuries via the Christian revolution under Constantine. Without which, apparently, the Church would not be as healthy today, nor so robust.

Endnotes

1. Galatians 4:4

2. T.G. Elliott, The Christianity of Constantine the Great (Scranton PA: The University of Scranton Press, 1996), p. 334. Cf. fn. 21.

3. Ibid.

4. Gottfried Arnold, Impartial History of the Churches and the Heretics, cited and discussed in Santo Mazarino, The End of the Ancient World, (NY: Alfred A Knopf, 1966), pp. 112-13.

5. Jesus prefaces his prophesy about the kingdom coming in power by indicating that some of his contemporaries would not taste death without seeing the power already developing. This prophesy could relate to the persecution of Nero (AD 64-68), which victimized some of the Apostles. That the imperial government had taken notice of Christianity, and had seen fit to subject it to persecution, would indicate that Rome saw the new religion as having become sufficiently threatening (i.e. powerful) to warrant state intervention.

6. Santo Mazarino, The End of the Ancient World, (NY: Alfred A Knopf, 1966), pp. 48-49/

7. Ibid., p. 121.

8. In second place would be the Holy Roman Empire, founded in 962 by Otto I (though ostensibly by Charlemagne).

9. Charles M. Odahl, Constantine and the Christian Empire, 2nd ed. (New York: Routledge, 2012), p. 280.

10. Johannes A. Straub, “Constantine as Koinos Episkopos: Tradition and Innovation in the Representation of the First Christian Emperor’s Majesty,” in Dumbarton Oaks Papers, no. 21 (Washington, D.C.: Center for Byzantine Studies for Harvard Univ., 1967), pp. 37-55.

11. Odahl, supra, pp. 133, 137.

12. To have recourse to the sword … through zeal for justice, and by legitimate authority, as it were of God, … is not to grasp the sword, but to employ it as a commission. St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica II 40.

13. HC Frend, The Rise of Christianity (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1984), p. 22.

14. Battle of Muret, September 12, 1213; Battle of Lepanto, October 7, 1571; Battle of Peterwardein, August 6, 1716.

15. Holy Bible (Confraternity ed.).

16. Warren H. Carroll, The Last Crusade: Spain 1936 (Front Royal VA, Christendom Press, 1996), pp. 206, 212.

____

See also my “America and Ancient Rome: Comparisons”

And the four part series for the 17th centennial, “Christian Revolution Under Constantine”