Divergent Trilogy Tackles Genetic Engineering and Genetic Discrimination

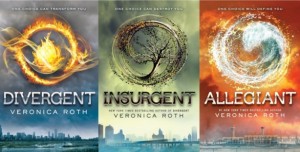

Divergent is the latest of the teen dystopian future trilogies to hit the big screen. I have read all three books, Divergent, Insurgent, and Allegiant. Is it not my favorite trilogy in this growing genre, but I know that teens everywhere love it.

I do appreciate that Veronica Roth has tackled some of the most difficult issues that will face the younger generation. The third book, Allegiant, takes human genetic engineering and genetic discrimination head on.

Here is a little background. The trilogy begins in a walled city where everyone lives in five factions depending on their personal qualities. The Amity are all about peace and friendship. The Candor are brutally honest. The Erudite are incredibly clever. The Dauntless are risk-takers devoid of fear. And the Abnegation are selfless and driven to serve others.

If a person does not fit in one of these boxes, they are called “divergent,”, and being divergent is a dangerous prospect. The main character, Tris, is divergent. She spends the first novel trying to hide it and the second novel discovering she needs to get outside the city to see what lies beyond the walls.

In the third book, we learn why the city is set up the way it is. On the outside, Tris finds out the city is a genetic experiment to try and fix damage that was done generations ago. With typical arrogance and ignorance, human beings began to genetically alter themselves to be better. The genetic engineering was done in a germ-line fashion and had unforeseen side effects that generations later were still wreaking havoc. One character involved in running the experiment explains:

“But when the genetic manipulations began to take effect, the alterations had disastrous consequences. As it turns out, the attempt had resulted not in corrected genes, but in damaged ones,” David says. “Take away someone’s fear, or low intelligence, or dishonesty . . . and you take away their compassion. Take away someone’s aggression and you take away their motivation, or their ability to assert themselves. Take away their selfishness and you take away their sense of self-preservation. If you think about it, I’m sure you know exactly what I mean.”

I tick off each quality in my mind as he says it—fear, low intelligence, dishonesty, aggression, selfishness. He is talking about the factions. And he’s right to say that every faction loses something when it gains a virtue: the Dauntless, brave but cruel; the Erudite, intelligent but vain; the Amity, peaceful but passive; the Candor, honest but inconsiderate; the Abnegation, selfless but stifling.

The genetically damaged were isolated in the city and placed in factions in an attempt at peaceful coexistence and a chance at fixing the results of the genetic engineering. We find out that being divergent, not wholly in one faction or another, is actually a sign of genetic healing.

Outside the city is not all peaches and cream either, however. Those who still live with “genetic damage” are second class citizens, seen as lesser humans, and they are unable to hold certain jobs. Those who were not genetically engineered are considered “genetically pure,” and they run the place. It becomes clear that both the “damaged” and the “pure” are capable of great evil and great good regardless of their genetic make-up.

Roth address two important themes that today’s teens need to be thinking about. The first is the wisdom of genetically altering ourselves to be “better.” In Allegiant, we discover that the attempt goes horribly wrong and it affects generation after generation. Anyone reading this trilogy has to ask themselves if it is a road we should even begin to go down.

The second theme is one we are already grappling with: genetic discrimination. Are we defined by our genes “detective” or otherwise? Or are we more than a sequence of nucleotides? It seems clear to me that this trilogy answers “No” to the former and “Yes” to the latter.

Unfortunately there is a hint of some premarital sex in the last book, but I still want to thank Veronica Roth for tackling tough issues in biotechnology in a way young people love. I hope this trilogy gives them pause in a world that thinks science can solve any problem. I hope they see that being human is not a problem that needs to be fixed.