Justice Denied in Peru’s Sterilization Campaign

Anne Roback Morse also contributed to this article.

Fifteen years ago, Peruvian President Alberto Fujimori, with the strong encouragement of the Clinton administration, ordered a nationwide sterilization campaign. At least 300,000 women were sterilized by “mobile sterilization teams” on a Chinese model, many under duress. Some died.

Fifteen years ago, Peruvian President Alberto Fujimori, with the strong encouragement of the Clinton administration, ordered a nationwide sterilization campaign. At least 300,000 women were sterilized by “mobile sterilization teams” on a Chinese model, many under duress. Some died.

PRI sent a team of investigators into the country, documented the abuses, and held press conferences and congressional hearings in the U.S. and Peru. Because of our work, the sterilization campaign ground to a halt.

But Fujimori and his health ministers have never been called to account for these human rights abuses. And now it appears that they won’t be. The Peruvian state prosecutor Marco Guzman dropped the charges last Friday, because he was not convinced that the enforced sterilizations were “widespread or systemic.”

In fact, they were both.

Elected to a second presidential term in mid-1995, Fujimori, with the encouragement of the Clinton State Department and the U.N. Population Fund, ordered his Ministry of Health to focus its efforts on sterilizing women by tubal ligations. He set national targets for the number of sterilizations—100,000 in 1997 alone—and demanded weekly progress reports. These targets and quotas alone are prima facie evidence of serious problems, since they were banned by the 1994 Cairo population conference on the grounds that they always lead to abuses.

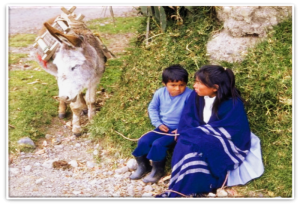

PRI investigators found that the mobile sterilization teams were comprised of doctors and nurses who often had no previous training in obstetrics or gynecology, but were nevertheless sent out to the countryside to sterilize women at grotesquely misnamed “ligation festivals.” Officials brought women to the sterilization sites by subjecting them to harassment, verbal abuse, and threats. Among other things, they told the indigenous Peruvian women that, unless they submitted, their children would be denied medical care or food assistance.

Fujimori was originally prosecuted for genocide, which under international law is defined as “any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, such as:… (d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group” (emphasis added).

The case can certainly be made that the Peruvian sterilization campaign was genocidal, since it pitted the ‘haves’—the largely urban descendants of Francisco Pizarro’s conquistadores—against the ‘have-nots’—the largely rural descendants of the ancient Incas. The majority of the sterilization teams were sent to the altiplano, or the Andean mountain valleys, and the majority of the sterilizations were done on the Quechua-speaking inhabitants of those regions. This concentration on the impoverished Indios, living a hardscrabble existence on mountain plots, is why these crimes could rightly be characterized as genocide.

After the Peruvian prosecutor dropped the charge of genocide, human rights groups then tried to convict Fujimori for crimes against humanity. Crimes against humanity are defined as: “any of the following acts when committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian population, with knowledge of the attack:…(g) Rape, sexual slavery, enforced prostitution, forced pregnancy, enforced sterilization, or any other form of sexual violence of comparable gravity….” (emphasis added).

Despite the evidence, Guzman dropped these charges against Fujimori as well. We agree with the director of the center for legal studies at C-FAM, Stefano Gennarini, that this move “is indicative of how much currency population control still has, and how countries don’t value the rights of poor and marginalized groups.”

Fujimori’s case was the first criminal trial for systemic forced sterilizations since the Nuremberg trials. And it is important because it could have set a precedent. After all, those who do not remember history are doomed to repeat it, and we do not want other women to have to go through the pain that many Peruvian women suffered.

Some of the families of women who died from being sterilized under duress still have not received the compensation promised them. Mamerita Mestanza died as a result of a botched tubal ligation in 1998. Her husband and seven children were promised 120,000 USD in compensation in 2003, but they still haven’t received a penny.

Meanwhile, the radical feminists who control the Ministry of Women’s Affairs ministry continue to draw their salaries while continuing to push poor Peruvian women into “Reproductive Health” programs that have nothing to do with reproduction and sometimes damage their health.

Fujimori light, you might call it.

——————

You can see PRI documentation of the abuses in Peru here:

Testimonies and Interviews:

Statement of Sra. Avelina Sanchez Nolberto at U.S. Congressional Briefing

Statement of Victoria Vigo Espinoza at U.S. Congressional Briefing

Interview between PRI investigator and Eduardo Yong Marta, President Fujimori’s health advisor

Briefings and Reports:

Human Rights and Reproductive Wrongs

Peruvian sterilization program targets society’s weakest

USAID Continues to Fund Family Planning Programs in Peru, Despite Verifiable Abuses