Lent, Ashes, and Death to Self

“[F]or dust thou art, and to dust thou shall return” (Gen. 3:19).

“[F]or dust thou art, and to dust thou shall return” (Gen. 3:19).

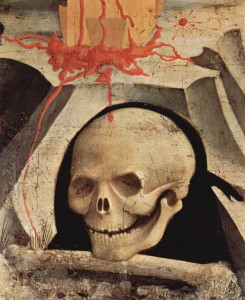

We are food for worms, and yet our culture, our modernist worldview, pretends that nature can somehow be betrayed. We worship the appearance of youth while we are alive, and when those around us give in to inevitability, we hide the reality of their rot, decay and morbidity behind funeral home doors and caskets, embalming fluid and makeup, and silly words like “passing.”

The truth is that you will die within the next hundred years, and reminding you of this truth is one of the primary purposes behind Ash Wednesday. The Church, in her 2000 years of Christian wisdom, knows that the discipline of ritual is an aid to ongoing conversion, and that spontaneity is not nearly as important as steadfastness. So every year, 40 days before the ultimate Sacrifice that the Church remembers at Easter, we are offered the preparatory discipline of Lent.

In a way, it’s the Church’s means of reminding herself not to get too big for her britches — that we are all merely dust and ashes. Ash Wednesday, then, is a day for remembering and contemplating our mortality. It brings to the forefront of our minds the relationship that connects us to our last end – Jesus – and the reality that we are radically and solely dependent on Him to overcome our inevitable fate: sin, and consequently death.

The head, as the Scriptural seat of pride, receives the ashen cross on Ash Wednesday as the priest says, “Remember, oh man, that thou art dust, and unto dust thou shall return.” We remember our createdness with a strange thrill of respect, say nothing, and simply return to our pews.

Wearing the ashes on our foreheads throughout the course of the day’s activities is a badge of Catholicism, a discipline and public witness to those things modern society decries: the reality of spiritual authority through the Church, death, penance for sin, and the hope of resurrection in Our Lord, Jesus Christ. And yet there is a somewhat contradictory truth present, so that Lent is a paradoxical illustration of our hope of happiness and bliss in death.

The Paradox of Life

The custom of ashes hearkens to the sacrificial burnt offerings of Old Testament Judaism, the sweet root of Catholicism; this was the only Old Testament offering that was wholly consumed on the altar when accepted by God. As the precedent to the New Testament, we study the Old Testament to more completely understand the worship that was pleasing to God, how Jesus fulfilled those requirements, and how the Church follows Him in pleasing God with our own worship.

Through the Old Testament sacrifices we learn that sacrificial worship pleases God. It must be through the Lamb of God Who takes away the sins of the world, of the best we own and are, it must be freely made, continual, and having offered a thing to be wholly consumed, we are left with a pile of ashes. Ashes, however, had their own profound place in the Scriptures.

They were always used in ancient times to denote human mourning and weakness. In Genesis 18:27 the lack of holiness in Sodom was paramount to the city’s worthlessness. With God, Abraham mourned the lack of purity and goodness there with sackcloth and ashes.

In 2 Sam. 13:14-19, Tamar’s grief over her incestuous rape was communicated through the ashes she threw on her head. Exodus 9:10 shows that God’s judgment is known through the presence of ashes. National humiliation caused the mourning in 1 Macc. 3:44-53, while suffering, disease and affliction were the preceding causes in Job 2:1-8.

Ashes are especially indicative of repentance in the Scriptures in several passages (Jonah 3:1-10; Job 42:2-6; Mal. 4:3; Matt. 11:21; 2 Pet. 2:6), so that together with the original connotations of the Old Testament sacrificial offerings, ashes came to predominantly indicate sorrowful contrition in the Scriptures.

In the Old Testament, suffering of all sorts may have been characterized by ashes, but as early as the prophets a new picture began to emerge. In Isaiah’s prophecies of the New Testament Messiah, there was born a new application for those dusty ashes, previously indicative of afflicted, brokenhearted captives who found themselves in prison, bound and mourning:

“The Spirit of the Lord God is upon me, because the Lord has anointed me to bring good tidings to the afflicted; he has sent me to bind up the brokenhearted, to proclaim liberty to the captives, and the opening of the prison to those who are bound; to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor, and the day of vengeance of our God; to comfort all who mourn; to grant to those who mourn in Zion – to give them a garland instead of ashes, the oil of gladness instead of mourning, the mantle of praise instead of a faint spirit; that they may be called oaks of righteousness, the planting of the LORD, that he may be glorified “ (Is. 61:1-3).

A garland instead of ashes. A crown for sorrow. A wreath for mourning. Gladness for repentance. Praise for humiliation. Hallelujah! According to the prophets, when the Messiah of God came, He would change our grieving and sorrow into something completely different. We will not mourn and cry forever. Praise God! After offering up our sufferings in communion with Christ’s, God gives us beauty in exchange for ashes.

In the New Testament, Jesus offers us a fuller picture for this exchange. In Matthew 5:1-12 we see the “ashen” lot of qualities of those populating the Kingdom of Heaven. The passage almost seems to read, “Blessed are the poor, the depressed, the weak, the malnourished, the dehydrated, the doormat, the persecuted, harassed and slandered.”

Jesus seems to teach that somehow these characteristics bring perfect happiness, or “blessedness,” yet one is left with the distinct impression that the qualifications are so miserable that he might not want to be “blessed” after all. Even so, somehow the magnitude of the blessings Jesus promises tempt one to take a closer look, as people with these “weaknesses” are said to experience largess, abundance, and favor, the meaning of “blessed.”

By their trials the righteous flourished…

The trouble with our reaction to these verses is the same one confronted by Ash Wednesday: it is the trouble of suffering and mortality. Simply put, we abhor it! We seek strength, power, praise, fame, glory, ease, luxury. “’You seek, therefore, a thing which is not only not needed, but which also obscures the glory of my power.’ Here [St. Paul] hints at another thing also, namely, that in proportion as the trials waxed in intensity, in the same proportion the grace was increased and continued…By their trials the righteous flourished” (Chrysostom on 2 Cor. 2600).

“Only faith can discern [God’s omnipotence] when it is ‘made perfect in weakness’” (CCC 268). Moderns often view weakness in themselves and others as distasteful and repugnant, something to be ignored or borne. Yet the Scriptures say that God only chooses the weak, and that He uniquely blesses the suffering.

We can, therefore, be comforted by and embrace the ashes we are left with when we offer everything to God, for even our weaknesses are strength when embraced and offered to Him to be wholly transformed and consumed on the altar of the Cross. Jesus embraced His own weakness, the sacrificial ashes, of His death, “despising the shame,” all the way, but it was the final, sure exchange of ashes for beauty, “the joy set before Him, [that] he endured the Cross” (Heb. 12:2).

The ashes of Lent then, should be viewed as a time to purposely trouble ourselves toward the renewal of who we really are before God. This is the core of the Lenten experience. To acknowledge, to anticipate the day when we will stand before God and be judged, to prepare well for the hour of our death, we must sacrifice our sin on the altar in the sure hope of rising to new life in Christ – the garland of life for our sacrificial ashes of sin.

Embracing our Lenten ashes means we recognize the need for deeper conversion. Conversion always involves “giving something up” in some form, but the goal is not to postpone sin for the duration of Lent, but to root it out of our lives forever. Conversion means completely leaving behind old ways of living, perceiving, and behaving in order to embrace the beauty and crown of new life in Christ.

To do that, we must actively acknowledge our weaknesses, our guilt for the sins that led to Christ’s Passion and death, and open ourselves to grief – no matter what provokes it. We must move through Lent from the mourning of ashes to the glory of garlands. The sorrow of Lent leads to the beauty and joy of renewal and conversion at Easter.

Let us pray for all of those who will die physically this day, and this Lent, and those who will die to sin in the next 40 days and be received into the Church at Easter. May we all receive garlands for ashes.