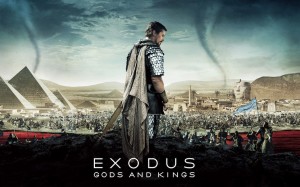

Movie Review: Exodus: Gods and Kings

Exodus–the story of Moses–proves beyond a shadow of a doubt that atheists make the best Bible movies (see my review of Noah). I don’t know that atheists necessarily make the best contemporary movies about faith or people of faith, but they certainly do the oldies well.

Exodus–the story of Moses–proves beyond a shadow of a doubt that atheists make the best Bible movies (see my review of Noah). I don’t know that atheists necessarily make the best contemporary movies about faith or people of faith, but they certainly do the oldies well.

Perhaps this is in part because they mine an amazing text/source that believers might take at face value and/or are afraid to delve to deeply into. Also, atheists are hungrier than us spoiled, slothful believers who take everything for granted.

Simply having faith doesn’t mean we have mastered the human depths of a Bible figure’s journey. That’s pretty much open to anyone. To do a Bible story well, an atheist filmmaker must suspend their own disbelief and ask “what if”? I think Ridley Scott has done that here.

Like a Boss. Like Bosses.

Does Christian Bale pull it off as Moses? Oh yeah. At first, I disliked his trim little facial hair and cropped-but-artfully-tousled hair that didn’t look like it fit the era, but it leaves him room for growth and aging.

Ramses is played by the unearthly, superlative, uber-uber Joel Edgerton. Edgerton plays Ramses (backstory: unaffirmed by his father) with complexity: a royal that is weak, sniveling, and yet utterly ruthless and driven at the same time. (He reminded me a bit of the dauphin in “Joan of Arc” with Ingrid Bergman.)

Bale is Welsh and Edgerton is Australian, and it just shows. Americans are too American and the British are too British. I’m really digging these other-accented male actors (include New Zealanders) for the Big Roles (although Brooklyn-born John Turturro as Seti, Ramses’ father, made me forget all his other, often humorous, deeply American roles).

Flaws and Applause

In general, this is a well-made film, part of a new generation of Bible films. I am thrilled that our visually-oriented youth are being treated to these nouveau masterpieces. Most young people have not seen any of the older Bible films or lives of Christ.

The special effects are phenomenal–nothing new that we haven’t seen in recent years, but it’s still awesome to see it applied to Bible stories–and it does pay to see Exodus in 3D. The dialogue is rather minimal–and once in a brief while unintentionally laughably simplistic or expository–but the great

Ridley Scott mesmerizingly pulls us through visual sequence after visual sequence of battles and plagues. I’m not usually one for epic films with wars and lots of noise and action, but Scott is a genius and is really moving the story ahead through the action-reactions of characters to these grandiose, sweeping events.

There are a few scenes that could have been re-shot. The actors looked like they were trying to remember lines, weren’t sure how to play the scene, or it just wasn’t their best take. Dude. Just reshoot.

But these are my only complaints. It’s a great film.

Ancient, Yet Contemporary

Although the Bible is an “ancient” text about ancient times and peoples, human nature doesn’t change, and so Exodus has a contemporary feel. I could totally relate to Moses as he struggled to relate to God.

I loved seeing this incredible, incredible man of God questioning, fighting with and arguing with God. Remember, Moses saw God. He did so many epic things like, oh, leading the Hebrew people to freedom after four hundred years of slavery, parting the Red Sea, the Ten Commandments, etc., etc. But I love how the film starts him off as a skeptical, practical man with no faith.

God

The film has ample room for God as a huge player, a huge character. In fact, God makes it abundantly clear that once Moses has obeyed (a very creative, two-way-street type of obedience), God will do everything. In a colossal way.

There are no other explanations for why the cataclysms visit the mighty Egyptian empire. It reminds me of a quote of Blessed James Alberione: “Always start from a stable, start in Bethlehem, because God wants to show that it is He who is doing everything. Those who begin the works of God with money are naive.”

This larger-than-life drama of the Exodus is faithful to Scripture (with some poetic license as it should have, but not as rock-and-roll as “Noah”), and although this event is so foundational for the Jewish people, it is also our foundation as Christians. As Pope Pius XII said, “Spiritually, we are all Semites.”

I couldn’t help thinking of the Easter Vigil liturgy and Fathers of the Church that rely so heavily on the imagery of the Exodus for celebrating Baptism and the Redemption: freedom, transformation through water, the Passover.

The supposed cruelty, arbitrariness, and unreasonableness of God is also dealt with–and not just that of the Hebrew God, but that of the gods of other peoples in the region. That there IS a diety(ies) is assumed, taken for granted, obvious, almost unquestioned . But just what this God is like is hotly debated: “What kind of God would…?” Would that we had these same questions today!

Theology of the Body?

This is a very male movie. Women barely play a part.

Sigourney Weaver is miscast as the young pharaoh’s mother, Miriam has two small (albeit significant) scenes. Zipporah, Moses’ wife, is truly the love of his life, but we see so strongly how faith, leadership, the direction of tribes, nations and history is patriarchal.

As I will always maintain, patriarchy–although a system massively open to massive abuse–is not evil, and in a certain sense, God has ordained and used this system throughout salvation history (it’s also deeply rooted in simple biology but has nothing whatsoever to do with superiority–just a different task in life than women).

It is up to men and women (with the onus on women) to bring to light and emphasize the unique identity, heroism and essential contribution of women throughout history and salvation history. And we do not have to do this in a strident way, just a firmly insistent, truthful, and complementary way.

It is up to us women to read the Bible with women’s eyes and see all the amazing strong women of God everywhere in the Bible–and imitate them. And yes, much of this revolves around motherhood and the protection of vulnerable human life (um, what could be more noble and important)? Men, too, are called to protect vulnerable life, but they do it in a different way.

Moses’ mother, his sister and Pharaoh’s daughter are directly responsible for saving Moses’ life as a baby. Liturgists have often commented what a tragedy it is that the story of the Hebrew midwives in Egypt is not included anywhere in our liturgical readings! (Exodus 1:15-21)

One more word about patriarchy and the absolute need for good men. For good men to lead. When good men lead, women and children flourish.

Just before the Synod on the Family, a very good man (who leads) said this: “I hope they start the Synod with ‘the father.’ Because if there is not a good father in the family, he will not do the right thing, and the children won’t know right from wrong. He must imitate St. Joseph when it comes to his wife, and their marriage has to be Christ-centered.”

I hope that men in particular will feel called to a deeper, truly masculine relationship with God through this film.

A Prayerful, Catechetical, Exegetical Experience

I hope audiences will sit back and consider their own wrestling with God, their own prayer life, their own dilemmas and choices alongside those of Moses. Enter into the story with their own story. I received tremendous insight through this film.

Many years ago, I was told by a Jesuit spiritual director that I could “negotiate” with God. “What?!” said I. “What do you think Abraham and Moses did?” he asked me. This conversation changed my life and my relationship with God forever.

Of course, the Jews already understand that as they have continuously and intimately wrangled with God and kept their conversation with him going for millennia: collectively and individually.

This bargaining with God is not meant to be a venal begging for things or circumstances that we want, but as intercession for the good, for others, to become better people ourselves. Although not all of Moses’ life is covered in this film, I was reminded of him so often “standing in the breech” for others.

There’s a touching and tender scene regarding the Ten Commandments where it is evident that Moses is still free at every step to agree or disagree with God. And of course, by this time, the fiery Moses had become “by far the meekest man on earth” (Numbers 12:3).

Faith and Love

There is much explicit talk about “faith” in this film, but little about love (beyond familial love). Of course, for men, love is often summed up in silent deeds. If a man loves you, he’ll mow the lawn and fix your car but never think to say: “I love you.” Again, think St. Joseph who says exactly nothing in the Bible.

I wonder if Scott was toying so much with faith that he forgot about the great love of God for Moses and Moses for God that motivated everything. Or maybe it is just implied. At UCLA, we were taught that in all good screen love stories, “I love you” must be shown in a plethora of different ways whether or not it is ever voiced.

The story of God and Moses is nothing if not a love story amongst God, Moses and “his people.”