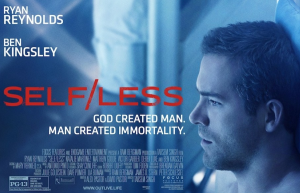

Movie Review: Self/less

The idea and ideology of “transhumanism”: that human beings are basically just brains in containers, and that if we could just find a way to upload our brains into computers or robots or such–we could live on forever–is the subject of the new film Self/less. It was also the subject of the recent film Transcendence. (Incidentally, Ray Kurzweil, director of engineering at Google, is a transhumanist–that is, he holds this view of the human person and is seeking to make it happen.)

The idea and ideology of “transhumanism”: that human beings are basically just brains in containers, and that if we could just find a way to upload our brains into computers or robots or such–we could live on forever–is the subject of the new film Self/less. It was also the subject of the recent film Transcendence. (Incidentally, Ray Kurzweil, director of engineering at Google, is a transhumanist–that is, he holds this view of the human person and is seeking to make it happen.)

The trailer to this film looked intriguing and the premise clever, but I’m sorry to report that the actual execution of the film is a shambles.

An older, powerful New York business tycoon, Damian (Ben Kingsley), has six months left to live. He lives alone and has one grown daughter whom he rarely has contact with–a fact that he begins to regret. He decides to look into a company that does “shedding” or life extension.

It’s all very secretive and extremely expensive, but the company’s head tells him they aren’t as interested in the money as they are in prolonging the existence of “the world’s great minds” (eugenics, anyone?). Just what Damian has ever done for humanity (or will do in his new skin) is unclear.

The shedding process is basically putting Damian’s mind/consciousness into a younger man’s body (supposedly one grown in the lab). The younger man is played by Ryan Reynolds (Canada’s Ben Affleck).

The process goes well enough until Damian starts to have flashbacks and memories that are not his own. In order to keep these flashbacks at bay, he must take pills provided for him by the company, who dole them out very sparingly.

It starts to become very clear that Damian wasn’t told, and presumably didn’t ask about, all that “shedding” entails and what the future really holds for him. The company is ever-present in his life and we start to see that he is practically owned by them. He is a guinea pig, an experiment.

A woman and her little girl enter Damian’s life, and he begins to realize that they are something worth living and perhaps dying for. The girl is like a stand-in for the daughter he never spent much time with, so there’s a kind of redemption here. But if we only have one life to live and we refuse to repent–will we really repent in our extended life? (Failure to repent while you can is probably the worst kind of procrastination.)

“It is appointed for men to die once” (Hebrews 9:27). “You are merciful to all, you overlook our sins and give us time to repent” (Wisdom 11:23).

The way it’s presented, it doesn’t seem like we are supposed to “like” this idea of shedding. However, I wonder if some people in the audience might be saying to themselves, “Yeah, I’d do that.” How it actually occurs scientifically is never explained and the process (two MRI-like machines for the two bodies) is reminiscent of the 1950’s sci-fi movie machines that “just do the job.” By not giving us any details, it’s a bit of a leap for the imagination, but the leaping doesn’t stop there.

The plot has as many gaps and holes as a slice of Swiss cheese. Also, important plot points are not made crystal clear and it takes us a while to catch up. The one thing you don’t want audiences to keep saying to themselves over and over is: “But why don’t they just…?” and I found myself repeating that internally many times.

Even though it seems we’re supposed to have big misgivings about “shedding,” it’s stated over and over in the film that the body is a “prison” and an “empty vessel.” Bad Theology of the Body! Bad Theology of the Body!

“The human body can never be reduced to mere matter. It is a spiritualized body, just as a person’s spirit is so closely united to the body that they can be described as an embodied spirit” (John Paul II, “Letter to Families,” 19).

There is lull after lull in the action and tension, even when characters are in mortal danger. There are good isolated scenes and sequences, but the storytelling seems to get lost in these semi-detours.

The woman’s character is totally laughable. She is, well, a dumb brunette, and her lines are ridiculous and empty. She seems to accept all the preposterousness visited upon her extremely well. Her reactions and engagement with the drama are full of false notes. I wish I had a dollar for every time she whines: “WHAT’S GOING ON??!! IS EVERYTHING OK??!!”

Another example of female air-headedness in dialogue was the stereotypical character of Damian’s neglected daughter. When Damian tries to make things right with her shortly before his shedding, she spouts (for the audience’s sake) these “on the nose” lines: “Sure. You were never there for me when I was growing up. You hardly ever try to get in touch with me. You think your money can solve everything.”

Much of the story is predictable. I was able to keep guessing what would happen next (something I don’t usually have a talent for): “I bet…yup!” So there was very little element of surprise, except for the ending which has a sizable twist.

One good takeaway was: Our choices affect others, a whole web of people. Even when we think we are just making choices for ourselves, there’s no such thing.

Also, perhaps a film like this can give us pause: Do I accept my bodiliness, the conditions of my creatureliness, my limits? Of course we want to be immortal. God wants us to be, too. But He’s the Man with the plan. Can we accept the reality we’re living in as the Creator designed it? (Satan couldn’t. Adam and Eve couldn’t.) Do we even know when we’re playing God anymore?

People in my audience were guffawing at super-serious moments, and a few people simply left early–I almost did, too, which is something I never do. I rarely tell people not to bother with a film, but if you’re at the cinema? Keep moving past Self/less. There’s nothing to see here, folks.