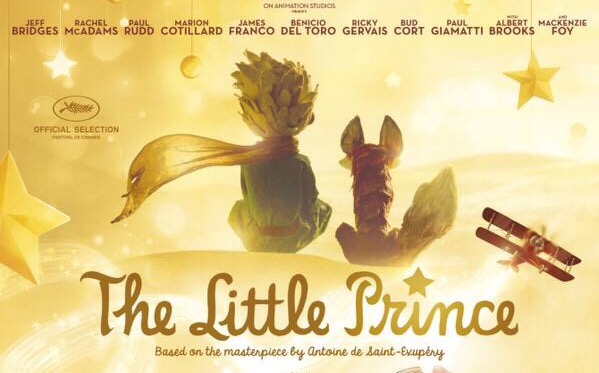

Movie Review: The Little Prince

The beloved classic, The Little Prince, was released simultaneously in theaters and on Netflix, and will not disappoint fans of the fable. Jeff Bridges’ rich, warm, craggy American voice brings to life Saint-Exupéry, the author and aviator. Three different kinds of storytelling visuals are utilized: the now-familiar computer animation, sporting oversized heads and large, expressive eyes (Inside Out, Despicable Me, etc.); stop-action figures, and Saint-Exupéry’s own line drawings brought to life.

The beloved classic, The Little Prince, was released simultaneously in theaters and on Netflix, and will not disappoint fans of the fable. Jeff Bridges’ rich, warm, craggy American voice brings to life Saint-Exupéry, the author and aviator. Three different kinds of storytelling visuals are utilized: the now-familiar computer animation, sporting oversized heads and large, expressive eyes (Inside Out, Despicable Me, etc.); stop-action figures, and Saint-Exupéry’s own line drawings brought to life.

This presentation of The Little Prince is couched within a contemporary story of a little girl and her mother, which fleshes it out and grounds the sometimes metaphorical etherealness of the story. There is even a counterbalance of cynicism and incredulity on the part of The Little Girl (no name!) who is being raised by an over scheduling, overly pragmatic, overachieving mother.

All The Little Girl knows is science, facts, calculations and her “life board” (a plan of “what is essential” that her mother has concocted, which lays out every single hour, day and year of The Little Girl’s life). The Little Girl’s watch alarm sounds when it’s time to move on to her next “project.” She is hardly a child at all. Her surroundings are gray and drab.

Learning How to Be a Kid

When The Little Girl and her mother move to a new neighborhood, they wind up next to a tall, skinny, ramshackle Victorian house in disrepair (shades of UP). Like its ancient inhabitant (The Aviator/Saint-Exupéry), it’s out of step (in a good way) with the austere, cube-like, cookie-cutter homes in what is obviously a new development.

Since her mother is at work non-stop, The Little Girl (about nine years old) is left to her own devices for most of the day and night, or rather she is left to her “life board” which consists mainly of studying in order to secure a certain, successful future. (Hers, of course, is a terrible life, and is actually child endangerment.)

The Little Girl makes friends with The Aviator rather quickly (unbeknownst to supermom), begins spending lots of time with him and slacking on her studies. (Again, sending a terrible message. I don’t believe we should automatically demonize men, young or old, as potential creepy-deepy predators — but a little girl [or boy], left alone day and night, hanging out with an old guy her mom doesn’t even know?)

On the up side (pun intended), The Aviator’s home and yard is an unkempt playground of sorts. In contrast with The Little Girl’s Soviet-esque home, Saint-Exupéry’s environment is colorful, full of birds, flowers, music, whimsical widgets and his broken-down plane that he is forever trying to restart.

Saint-Exupéry lets The Little Girl be a kid. In fact, he teaches her how to be a child. How to take normal kid risks (like climbing a tree), to believe in herself, that she is capable to do things, even if she hasn’t studied them and they’re not on the life board.

Little by little, on paper and verbally, Saint-Exupéry tells her the story of The Little Prince. Skeptical at first, The Little Girl is eventually captivated by the tale. She rolls the characters and dialogue and lessons around in her head. She discovers artifacts that represent The Little Prince and his world, or shall we say “worlds,” or shall we say asteroids! The rose, the fox, the serpent, the sands of the Sahara all come alive in her underused imagination. But The Little Girl never loses her practicality, and when she comes to the end of the story, she is furious.

SPOILER ALERT: If you don’t know the ending of The Little Prince, I’m revealing it here. The Little Prince chooses death (by serpent bite–let’s call it what it is: suicide) in order to go back to his asteroid–just exactly how this all works is never explained–to be with the rose that he ultimately loves but abandoned (because of her vain demands and because “they were too young to know how to love”).

Validating Childhood

This ending does not sit well with The Little Girl at all, and in anger, she cuts off her friendship with the pilot. Worse yet, shortly thereafter, the old man is rushed by ambulance to the hospital. He had been hinting to her all along that he was preparing to “leave.” His health had been obviously failing, but in her child’s mind, The Little Girl assumed he was talking about going in his plane on a trip from which he wouldn’t return.

The Little Girl and her mom visit Saint-Exupéry in the hospital and amends are made. However, the old man is dying. But The Little Girl hatches a plan. She believes that no one less than The Little Prince himself can save her dear, elderly friend. And here’s where it all gets fantastical and stretches the bounds of our most magical thinking.

The Little Girl takes off in Saint-Exupéry’s old plane in search of The Little Prince. She finds him, but he’s all grown up. In a bad way. And here’s the real message of The Little Prince, both the book and the movie: Growing up isn’t the problem, it’s forgetting what it’s like to be a child that’s the problem. Because to see the world as a child has great value.

The Little Prince validates kids being kids as such a very good thing. They are told that they need to take their childhood with them into adulthood. Bravo.

In the big city, The Little Prince has been brainwashed to a different understanding of what is “essential”: that which makes money. Working hard. Commerce. That which can be bought and sold. (This is a clever and brilliant examination of how words and values can get so twisted that they can have opposite meanings, but not just subjectively–“happiness is different things to different people.”)

We are made to understand that Saint-Exupéry is right about what is essential, not big business.

Theology of the Body Fail

The trouble with The Little Prince (the original book and this movie) is its sidestepping of death with euphemisms. Why can’t we teach kids about death?

Because then we’d have to say something real about God, and heaven forbid, we can’t do that. So what we’re stuck with is Disney–Life of Pi—Kung Fu Panda “Believe!” nonsense.

The Little Girl rightly demands of the aviator to tell her exactly what happened to The Little Prince, and she gets a wussy “I choose to believe….” She gets: “He’s always with me, I hear him laughing in the stars.”

There’s nothing wrong with this kind of poetry that we all use when we’ve lost a loved one and something they loved in life reminds us of them. But to shovel only this weak drivel into little and big Christian minds? Pshaw!

We know so much better. We have so much better. We get so much better. Our loved ones live on as they are, as persons, in God, with God. The redeemed will be reunited forever in a very real heaven.

We, God, death, life, the afterlife are not just some nebulous ball of sentimental mush. It’s all so very real. There will also be “a new heavens and a new earth” as the Bible tells us (so don’t be surprised at roses and foxes in “heaven”).

And do not get me started on the resurrection of the body in The Little Prince. The body is stated in no uncertain terms to be a shell that we leave behind. Zut alors!

Unfortunately, one of the most prominent messages of The Little Prince is that the spiritual is what’s most real, what matters most, what endures. The following favorite LP maxims are helpful and true, but only if understood in conjunction with the reality, the equal importance and continuing existence of the body in eternity: “Only with the heart can we see rightly.” “What is essential is invisible to the eye.”