Norplant is Back–Under a Different Name

Elizabeth Crnkovich also contributed to this article.

The population controllers have long dreamed of chemically sterilizing women for extended periods of time. That was the idea behind Norplant I, which consisted of six silicon capsules loaded with levonorgestrel that, implanted permanently in a woman’s body, was intended to shut down her reproductive system for up to five years. And it is this same idea that is driving the release of Norplant II, touted as “one of the most effective reversible contraceptives available.”

The population controllers have long dreamed of chemically sterilizing women for extended periods of time. That was the idea behind Norplant I, which consisted of six silicon capsules loaded with levonorgestrel that, implanted permanently in a woman’s body, was intended to shut down her reproductive system for up to five years. And it is this same idea that is driving the release of Norplant II, touted as “one of the most effective reversible contraceptives available.”

Except that, if the history of Norplant I is any guide, the second generation of this device will prove just as dangerous as the first.

No sooner had Norplant been approved by the FDA in 1990 than woman who received the implant began reporting serious side effects. By 1996, over 6,000 complaints of “adverse medical consequences” had been filed by American women who were suffering from various Norplant-related ailments, from heavy bleeding and vision impairment to general malaise and lack of appetite.

But these problems paled in comparison with those suffered by women overseas, perhaps because these latter were more often malnourished and in poor health to begin with. PRI investigations revealed that these women, instead of just suffering from vision problems, sometimes went blind, and instead of just suffering from a general feeling of malaise, were sometimes actually bedridden for months on end. And when they sought to have the troublesome implants removed, their requests were turned down by population control officials. They were forced to continue in pain and suffering, and sometimes died.

So it was that PRI in 1996 launched a media campaign against Norplant, advising American women who were suffering serious side effects from the device to contact legal counsel. We also filed a “citizen’s petition” with the FDA to have Norplant taken off the market.

Both of these efforts bore fruit. Faced with tens of thousands of lawsuits from injured women, the original manufacturer, Wyeth-Aherst, in 2002 reached an out-of-court settlement with the victims. That same year it took Norplant I off the market in the U.S., in an obvious effort to stem the financial hemorrhaging caused by the lawsuits.

It was a different story overseas. Wyeth-Aherst continued to manufacture, and USAID continued to purchase, millions of Norplant I to use on women in the developing world. Such women were, after all, easy targets. They lacked the means to fight back legally, and their complaints were brushed off by local health agencies complicit in population control programs. USAID finally ended its contract with the manufacturer in 2006, after PRI called attention to the obvious double standard at work here: How can the U.S. continue to promote the use of a drug/device overseas, we asked, that is so dangerous it has been taken off the market in the U.S.?

Now the same thing is happening all over again. It turns out that the new manufacturer, Bayer HealthCare, has no plans to market Norplant II in the United States. USAID has nevertheless signed a contract with the German pharmaceutical company to purchase and distribute the drug/device to its population control partners to implant in poor women around the world. Sound familiar?

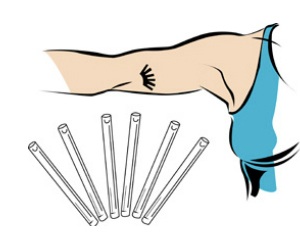

Both Norplants are implanted under the skin of the upper arm. Both contain the same “active ingredient”: levonorgestrel is a synthetic progestin. Like other such steroid-based drugs, it thickens the cervical mucus, sometimes (but not always) inhibits ovulation, and alters the lining of the uterus to prevent implantation. This means that women on Norplant can conceive children, who are then aborted after failing to implant in the uterus.

The main difference between the two Norplants is a relatively minor one. Norplant I contains six silicon rods containing synthetic progestin, while Norplant II contains only two, albeit larger, rods. In fact the two drug/devices are so similar that when the FDA approved Norplant II way back in 1996, it relied mostly upon Norplant I studies. We already know how well that turned out.

There is one more difference we should mention. Since “Norplant” has become a byword for a dangerous contraceptive drug/device, Norplant II has been given a new name. It will be marketed under the name “Jadelle”. Of course, a dangerous contraceptive by any other name is still a dangerous contraceptive.

The U.S. Agency for International Development picked World Contraception Day to proudly announce its new Jadelle program. We think the choice of this day oddly appropriate, since our aid agency apparently does have ambitions to contracept the world: It is ordering no fewer than 27 million implants at roughly $10 apiece from the manufacturer over the next six years.

What this means is that, even if this massive chemical sterilization campaign falters for some reason—such large numbers of poor women injured or dying as a result, or a Romney administration deciding that such an assault on the world’s fertility is a bad idea—the American taxpayer will still be on the hook to the tune of $270 million dollars.

Norplant I died a very public death some years ago, pilloried in the courts and pummeled in the media. One may well ask why it has now been resurrected, under a new name and with a new manufacturer.

The answer is that implanting long-term contraceptives in poor women is one of the cherished goals of the population control movement. USAID itself reiterated its commitment to this goal at the recent London Family Planning Summit sponsored by the Gates Foundation.

A woman on birth control can stop taking her pills. A woman on depo-provera can stop taking her injections. But Jadelle, like its predecessor, is impossible to remove short of surgery. A woman who has been chemically sterilized by Jadelle will stay sterilized—for five long years.