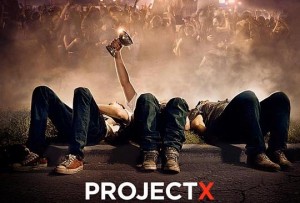

Project X and Wanderlust – On Being Lost in America

What does it take to be included, to feel a part of something bigger than yourself? In the past two weeks, two films, made for two generations, have sought to answer that question. Both are comedies, both rated R, and both come to the most dismal answers imaginable. I think it was Francis Schaeffer who argued that this is the first generation of people who do not know what they were made for. And it was G.K. Chesterton who said that people who reject God do not believe in nothing, they will believe anything. Those two ideas are on full, tragic display in Project X and Wanderlust.

What does it take to be included, to feel a part of something bigger than yourself? In the past two weeks, two films, made for two generations, have sought to answer that question. Both are comedies, both rated R, and both come to the most dismal answers imaginable. I think it was Francis Schaeffer who argued that this is the first generation of people who do not know what they were made for. And it was G.K. Chesterton who said that people who reject God do not believe in nothing, they will believe anything. Those two ideas are on full, tragic display in Project X and Wanderlust.

Project X, opening March 2, is another of the supposed “found footage” films. Thomas Kubs is turning 18 and, as luck would have it, his parents are going away for the weekend. Of course, the parents lay down the rules: only a few friends don’t drive dad’s car – rules that you are certain will be broken before the end of the film (it is the role of such rules). So it falls to Thomas’ “friends” – Costa, JB, and cameraman Dax to create a birthday party to remember. What begins as a “small” party of fifty mushrooms into an uncontrollable riot of 1,500. Teens drink, smoke weed, drop ecstasy, swim naked, throw up, and couple in every conceivable combination. Then the cops show up.

Wanderlust is a barely more sedate version of Project X. George and Linda are 30-somethings; he has been laid off and she has discovered that no one wants to buy her documentary (she appears to be on her sixth business idea). Unable to pay the mortgage, they leave Manhattan to move in with George’s overbearing, morally-challenged-but-successful brother Rick. On the way, they take a Twilight Zone-like detour into Elysium, which is pitched as a kind of communal paradise. In the morning they depart, headed for Rick’s, but once they arrive a family blow up drives them back. Committing themselves to join Elysium, they discover a commune with all of the stock characters. Adults drink, smoke weed, drop hallucinogens, swim naked, and commit adultery. The cops don’t show up. Whatever morality finally appears is far too little, far too late.

Both films suggest that ordinary people – by this the filmmakers mean middle class and average looking – are in search of the meaning of life, and desire to be a part of something bigger than themselves. But even when you know the destination, if you take the wrong road, all you end up being is lost.

Finding Yourself

In Project X, Thomas is introduced as one of the unpopular kids at school. He is bullied, drives a mini-van (the horror!), and in a very disturbing moment, is described by his own father as “kind of a loser.” He has three friends, each of whom plays a stereotypical “teen movie” role: the nerd, the sweater-vested cocky kid who thinks he is cooler/hotter/edgier than he actually is, and the cameraman (who you don’t see often, but it is intimated that he could be a dangerous loner). They are unsatisfied with who they are. They desire to be “legends” – to be “known” by others at their school. The way to accomplish this goal, they think, is to have a massive party, have sex with as many girls as possible, and to facilitate the maximum amount of intoxication and licentiousness for their party guests.

In Wanderlust, George and Linda believe that if they can find a way to escape the rat race, they can get in touch with their authentic, inner selves. But what they discover, pretty quickly, is that many of the people (primarily the leaders) in the commune are hypocritical, predatory narcissists. Seth, the commune’s “spiritual” leader, talks a good game about free love, but what he really wants is to separate Linda from George and then have her to himself. Role models for self-actualization are scarce.

The protagonists in these films are seeking to “find” themselves. They stand in for a culture that senses it is lost. Oftentimes, the search is framed as a quest for “authenticity,” as if the lives we currently lead are inherently dishonest. In order for us to locate our “authentic, real selves” we must first have an idea of what we seek. Otherwise, how will we know if we have found it? And such an idea implies a standard, a way of distinguishing between authentic and inauthentic, of a real human self rather than something less than human.

The problem is that our mediated culture – like the teens of Project X and the adolescent adults of Wanderlust — hates closing off options. As Thomas de Zengotita describes it in Mediated: “So mobility among the options in a virtualized environment gives to human freedom a new and ironic character. You are completely free to choose because it doesn’t matter what you choose. That’s why you are so free. Because it doesn’t matter. How cool is that?”

It is impossible to find meaning, for yourself, or anything else, in a world of unbounded freedom. In order for things to have value, they must matter. Ultimately, boundary-less cultures do not work any more than does a boundary-less world. If everything is permitted, if nothing is wrong, then nothing is right. Life ceases to have a moral dimension; objects, attitudes, and action lose their value, becoming just one more meaningless experience. In such a world no one will ever “find themselves” – there is no identifiable meaningful self to find.

Seeking Communion

In addition to personal self-fulfillment, the characters in these films also seek communion. They do not want to be alone; they want to be with other, like-minded people. The teens want to be legends, sure, but they also want acceptance from their high school peers, and are willing to do anything to get it. But even a moment’s reflection on the whole high school experience tells us that such acceptance is fleeting at best – often dissolving upon graduation.

George and Linda also desire community – but they cannot find it in their 400-square-foot, over-priced Manhattan “mini-loft,” or in Rick’s antiseptic McMansion. Community isn’t in Elysium either; it just takes them a bit longer to figure that out. Everywhere they turn they find false community: from the over-indulgent real estate agent (whose attitude toward George and Linda shifts dramatically when the buyers soon try to become sellers), to the not-so-happily married Rick who is constantly at odds with his self-medicating spouse, to Seth, the Elysium leader who is looking for a chance to sell out his commune.

What is ironic is that in both of these films, everyone is trying to find community in every place except the one that works best (though not perfectly): Church. Even noted atheist Alain de Botton argues in his essay “Religion for Everyone” that the church is particularly good at building community (and ethics, and education) – he just misses the reason why this is so. He thinks that you can tear the heart out of the church – remove God – and still get the function of His Body.

Church community functions because sin is the great leveling factor. G.K. Chesterton called sin a “fact,” and the church’s recognition of it was one of the first signs to him that its message was true. Church also functions because the message and gift of Jesus Christ know no distinctions between people. The Scriptures note that “all have sinned,” but our redemption is God’s free gift to all who believe. Despite the track record of the church in providing community, it is the place of last resort (or, for most directors, no resort) in many Hollywood movies. So the characters in their films keep casting about, and if audiences project a few days or a few years beyond the closing credits into the lives of these characters, they know that whatever substitute for community has been provided it ultimately will not last.

Ignoring or Laughing Off Consequences

One way in which filmmakers get away with making demonstrably false claims about living an authentic life or locating true community is that they keep audiences from contemplating the actual outcome of character choices in the real world. Audiences laugh when they hear that one of the characters in Project X gets out from under the criminal charges associated with the party, but is facing three paternity suits. See, the character got what he wanted from the party: a chance to have multiple, meaningless sexual encounters. Boys will be boys. What the viewer never sees is the girls, a month after the party, stone sober now, looking at a positive pregnancy test and wondering what they are going to do. A number of teens are shown taking ecstasy and downing the tablets with, or after consuming, tremendous amounts of alcohol — yet the only consequence is that a few people throw up, but that’s about it. No one is rushed to the hospital (or the coroner), no one is seen regretting choices made under the influence of drugs and alcohol, and no one heads to the doctor with chlamydia, herpes, or worse.

Wanderlust, which revels in much of the same behavior as Project X, adds adultery as a source of humor. But talk to anyone who has been the real-world victim of an adulterous spouse. No one is laughing. If a marriage survives an affair, it is usually the product of months or years of rebuilding trust, not a spur-of-the-moment change of heart.

In 1982, Neil Postman noted in The Disappearance of Childhood, “Civilization cannot exist without the control of impulses, particularly the impulse toward aggression and immediate gratification. We are in constant danger of being possessed by barbarism, of being overrun by violence, promiscuity, instinct, egoism.” Project X is a film made by adults, which (although rated R) is aimed firmly at immature teens to encourage the very activities that Postman wisely warns against. After the screening of Project X, the consensus of the audience was that this was an “awesome” film. I wonder how responsible the filmmakers will feel if their movie encourages more teens to imitate their new screen heroes – young people with no impulse control, no heed to the consequences of their actions. It doesn’t have to be this way.

Being Known

Every year, films such as Project X and Wanderlust are released, and a certain segment of the population eats them up. But the lie can be maintained for only so long. Experience is a ruthless teacher, and when people adopt the worldview promoted by these kinds of films, personal disaster is often the result. And what was it all for? To get a shot at being special, to find camaraderie in the outrageous, and then it all comes to nothing.

Everybody wants to be what they were meant to be. Everybody wants a sense of belonging to someone or something beyond themselves. They want to be known. C.S. Lewis, in his sermon “The Weight of Glory,” speaks of what it is like to be what we are: a creature before our Creator; what we were made for: to be a part of His Kingdom; and to revel in the fact that we are known by God. If we are followers of Jesus, the God of the Universe will one day smile on us, recognize us, and say, “Well done, my good and faithful servant. Enter into the joy of your Master.” On that day, no rave, no quest for self-fulfillment will remotely compare.

Life will kick you around. Foolish pursuits have a way of exacting their toll on our lives. But the underlying desires to be known, loved, a part of something great – these are all natural and good. People just need right direction so that they will understand how to fulfill these desires. The directions Hollywood provides are often bad, destructive, and spiritually lethal. The church has the better Way. Share it.