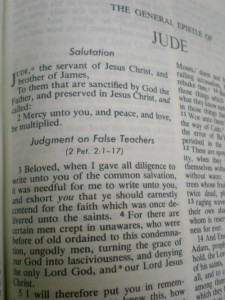

The Epistle of Saint Jude: Epilogue of Salvation; Prologue of Eternity

The Epistle of Saint Jude is the final letter in the New Testament before the Apocalypse and one of the shortest books in the Bible. Only once does a selection from Jude appear in the lectionary, on the eight Saturday of Ordinary Time in Year II but the brevity and obscurity of the letter is not indicative of its importance. Neither is its placement in the Bible as second-to-last. For precisely for these reasons — brevity, obscurity, and placement — Jude is a significant part of the biblical canon and should therefore be revered for what it is: the inspired Word of God. It is a true gem of Sacred Scripture and must be given the devotion and interest befitting a work of literature written by a man who heard the preaching of Jesus with his own ears and witnessed the Lord’s miracles with his own eyes. Thus the first shall be last.

The Epistle of Saint Jude is the final letter in the New Testament before the Apocalypse and one of the shortest books in the Bible. Only once does a selection from Jude appear in the lectionary, on the eight Saturday of Ordinary Time in Year II but the brevity and obscurity of the letter is not indicative of its importance. Neither is its placement in the Bible as second-to-last. For precisely for these reasons — brevity, obscurity, and placement — Jude is a significant part of the biblical canon and should therefore be revered for what it is: the inspired Word of God. It is a true gem of Sacred Scripture and must be given the devotion and interest befitting a work of literature written by a man who heard the preaching of Jesus with his own ears and witnessed the Lord’s miracles with his own eyes. Thus the first shall be last.

The Bible is meant to be taken as one story, and can be read in its entirety, front to back, cover to cover, from the words “In the beginning” (Genesis 1:1) to “Maranatha! Come, Lord Jesus” (Apocalypse 22:2). No doubt this is a formidable task. All books in Scripture are important and unique. Jude is special because it is the final stop on the journey through the Bible before the pilgrim crosses the threshold and enters the new and heavenly Jerusalem (Apocalypse 21:9ff). Jude is the epilogue to salvation history and the prologue to eternity.

The New Testament Letters serve as explanations to the gospel and to support the Church and to help Christians remain firm in the truth we have received through Divine Revelation. Of the twenty-one New Testament epistles, thirteen are attributed to Saint Paul, and apart from the gospels, constitute the portion of the New Testament with which Catholics might be most familiar, since Paul’s writings appear so frequently in the lectionary. The Epistle to the Hebrews is neither a letter nor was it addressed to the Hebrews (nor was it written by Paul) and is in a class by itself; it is a lengthy sermon characterized by its treatment of Christ’s eternal priesthood and written in highly stylized Greek prose. The remaining seven “catholic” letters, written by saints Peter, James, John, and Jude, were written to the universal Church, “catholic” being a translation of the Greek word for “universal.” They address multiple themes and issues and appear in the lectionary less frequently than Paul’s works or even Hebrews but they are equally vital to the Catholic faith and understanding of the story of God in Sacred Scripture. Because they are short, they can be read and reread and are the perfect conversation starters for bible study and for the personal faith journey.

Jude is singular because it is unknown and because it is so small that it cannot even be divided into chapters. The work serves as a reminder of God’s glorious and frightening dealings with humanity. Not only is it the shortest but its prose is textured differently; unlike other New Testament writers the author of Jude draws from the original Hebrew scriptures and apocryphal texts, that is, stories written by ancient authors that were not determined to have been written under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit or that did not express sound Christian doctrine. “Jude the Obscure” packs a lot of history and mystery and a little good old fashioned fire and brimstone into the epistle’s twenty-five verses, giving it great power, beauty, and originality, a clap of thunder and a bolt of lightning from the steel-gray sky beneath which stand naked and exposed the malefactors who stand for what the Church stands against: the truth and reality of Divine Revelation that is Jesus Christ.

Jude is singular because it is unknown and because it is so small that it cannot even be divided into chapters. The work serves as a reminder of God’s glorious and frightening dealings with humanity. Not only is it the shortest but its prose is textured differently; unlike other New Testament writers the author of Jude draws from the original Hebrew scriptures and apocryphal texts, that is, stories written by ancient authors that were not determined to have been written under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit or that did not express sound Christian doctrine. “Jude the Obscure” packs a lot of history and mystery and a little good old fashioned fire and brimstone into the epistle’s twenty-five verses, giving it great power, beauty, and originality, a clap of thunder and a bolt of lightning from the steel-gray sky beneath which stand naked and exposed the malefactors who stand for what the Church stands against: the truth and reality of Divine Revelation that is Jesus Christ.

Jude warns his community against “intruders” who seek to defile the “love feasts,” or Eucharistic assemblies, with elitism and heresies not important enough to be mentioned but significant enough to cause damage if left unchecked . Why draw attention to the malefactors and their profane speech? Nevertheless Jude — and all the catholic epistle writers — attacks them with the strongest of language. The family resemblance between the brother apostles James and Jude is clear; both possess rapier-like tongues and are not afraid to wield their pens like swords. Scoffers could scoff and be damned. The writer of Hebrews offers the same truth:

The Word of the Lord is a two-edged sword, penetrating even between soul and spirit, joints and marrow, and able to discern reflections and thoughts of the heart. No creature is concealed from him, but everything is naked and exposed to the eyes of him to whom we must render an account. (4:12-13)

Jude’s language is more caustic:

These people revile what they do not understand and they are destroyed like irrational animals. … They are like wild waves of the sea, foaming up their shameless deeds, wandering stars for whom the gloom of darkness has been reserved forever” (Jude 10, 13).

That is a poetic way of saying that these villains will be cast into the lake of fire.

The language of the letter is highly charged, energetic, and fiery, the story populated with an assortment of biblical and apocryphal ne’er-do-wells, a true rogues’ gallery with a lineup that includes: Cain, the Egyptians, Balaam, the soothsayer who rebelled against Moses and Aaron and was swallowed by the earth, the fallen angels who happened to be at Sodom and Gomorrah for reasons unmentionable that night when fire and brimstone rained (when even Abraham’s prayers could not reveal ten righteous men), and the devil himself who argued against the burial of Moses (he slew an Egyptian) but is rebuked and defeated by the archangel Saint Michael. Apocryphal citations from the Assumption of Moses and I Enoch nearly cost Jude its canonicity (why such heavy usage of non-inspired material by an apostle?) and church fathers debated vigorously over its insertion in the canon but the material is clearly grounded in apostolic teaching, the preaching of the men who lived with, followed, listened to, and witnessed the miracles wrought at the hands of the Lord.

The author of the letter identifies himself as “Jude, the servant of Jesus Christ and the brother of James” (v 1). Apostleship alone gives Jude credibility among the hearers and readers of the ancient church and yet he felt it necessary to attach himself to James, his brother and the leader of the Jerusalem. Perhaps he was putting in a plug. James was martyred in AD 62 and some scholars think Jude was written before James’s death, which would make it one of the earliest books in the New Testament. The primary value of the letter is that it offers a view into the days when Jesus’s own blood relatives led the Church.

The Epistle of Saint Jude serves as the interlude necessary to carry the reader of the Sacred Page across the bridge from the New Testament proper to the Apocalypse, the final book in the Bible. By the time we arrive at such revelation — the gates of heaven thrown open and the welcome mat placed before the door — the letter serves as a reminder that the Bible is meant to be read as His-story. The Yahwistic presence in the prose looms large, lending force to the voice and command of the inspired author with whom was Jesus… in the beginning.

© 2011 Father Tucker Cordani