Continuity & Ecumenism: Heretics or Seperated Brethren?

While writing my self-published manuscript, New Things and Old: Re-Implementing Vatican II, I came to the realization that Vatican II could only be understood in light of past magisterial teaching and the sources of the Tradition. Taken by themselves the documents could lead even orthodox Catholics to formulate or embrace conclusions that were erroneous and run contrary to Catholic teaching.

While writing my self-published manuscript, New Things and Old: Re-Implementing Vatican II, I came to the realization that Vatican II could only be understood in light of past magisterial teaching and the sources of the Tradition. Taken by themselves the documents could lead even orthodox Catholics to formulate or embrace conclusions that were erroneous and run contrary to Catholic teaching.

This tendency was addressed by Pope Benedict XVI, who spoke of “two hermeneutics” or methods for how Vatican II should be interpreted and understood – the “hermeneutic of continuity and reform” and the “hermeneutic of discontinuity and rupture”. This hermeneutic is employed by various Catholics in regards to Vatican II. Some traditionalists read the documents of Vatican II as breaking from Church teaching and condemn it for doing so, while progressives and modernists come to the same conclusion but consider it a boon. The “hermeneutic of continuity and reform”, on the other hand, sees Vatican II as merely developing certain doctrines but teaching nothing contrary to what was officially taught before. This is the position of the Magesterium, as well as the one all faithful and orthodox Catholics are required to adopt.

Unfortunately this is not always the case. What has happened is that in certain areas, orthodox Catholics unwittingly and thus innocently apply the wrong hermeneutic. They believe that certain previous magisterial statements contradict Vatican II and therefore must not have been infallible as they are in error. Even when they attempt to defend Vatican II, they make the same mistake that those who apply the hermeneutic of rupture make.

One of the most common areas that this has occurred in is ecumenism. Let us take for example an excerpt from The Catholic Challenge, written by Dr. Alan Schreck. Dr. Schreck states in pages 203-204 that before Vatican II:

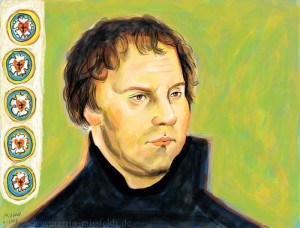

“it was common for Catholics and Protestants to think of each other as ‘heretics … [but] what a radical departure from such a posture is the teaching of the Second Vatican Council[:] ‘All those justified by faith through baptism are incorporated into Christ [and] therefore have the right to be honored by the title of Christian’ (Unitatis Redintegratio, 2). … Not only [this], but at Vatican II the Catholic church officially recognized for the first time the bodies to which these Christians belong as ‘churches and (ecclesial) communities.’”

If we examine Dr. Schreck’s commentary, we will discover that he employed the wrong hermeneutic.

Regarding the term “heretic”, we must begin by first finding out what it means and how it has been used by the Church. The word “heresy”, from which the term “heretic” is derived, comes from the Greek airesos, meaning “sect”, and was used by St. Peter in Scripture to refer to splinter groups such as the Gnostics. (2Peter 2:1) The term “heresy” has been used since the beginning to refer to “the formal denial or doubt by a baptized person of any revealed truth of the Catholic faith”, and the person who has done so as a “heretic”. (Attwater, Donald, ed. A Catholic Dictionary. New York: MacMillan Company, 1951)

A distinction, however, has long been made between “formal” and “material” heresy. St. Thomas in his Summa Theologica (II-II q.11, a.1) states that when “the heretical tenets [arise from] ignorance of the true creed, erroneous judgment, imperfect apprehension and comprehension of dogmas”, then “such heresy is merely objective, or material”, for “one of the necessary conditions of sinfulness — free choice — is wanting”. However, when “the will … freely incline[s] the intellect to adhere to tenets declared false by the [Magisterium]”, as in the case of “intellectual pride [or] the allurements of political or ecclesiastical power”, then the heresy is “freely willed” and thus it is “formal” and “carries with it varying degree[s] of guilt”.

The Reformers have always been accused of formal heresy, but not necessarily Protestants who were born into those communions, who have often been considered only material heretics, as the Catholic Dictionary witnesses to:

“It can hardly be doubted that the vast majority of non-Catholic Christians are in good faith and labouring under invincible ignorance [and thus material heresy]. It is amusing to note, in this age when many people [anti-Catholic Protestants] boast that they are heretics and resent any stigma of orthodoxy, that the Church refuses them both the name and the odium attaching to it” [emphasis mine].

At times the Magisterial documents before Vatican II did refer to Protestants as “heretics”. However, these documents refrained from using the term “heretic” when addressing Protestants in a fraternal spirit of invitation and dialogue, using them only when addressing the Catholic faithful alone and when the negative connotations attached to the term were fitting, such as when referring to non-Catholic Christians in certain anti-Catholic activities. In fact, some Popes before Vatican II used the term later adopted by Vatican II — “separated brethren” or “separated children”, as Pope Pius XI did in Mortalium Animos (paragraph 12) and as Pope Pius XII did in Orientalis Ecclesiae. (paragraph 38) While one can debate the wisdom of this change in the current environment, it is not unprecedented.

Even in this different environment, it is incorrect to say that the Popes have completely abandoned the previous approach. Pope St. John Paul II, when speaking about the proselytizing of Catholics in Latin America by Protestant groups, refers to them as “sects” ,which is the essence of heresy. (Ad Limina Address to the Bishops’ Conference of Brazil, September 5, 1995). Cardinal Ratzinger also used the same term in The Ratzinger Report to refer to certain proselytizing Protestant groups. (pages 117-118) The fact remains that Protestants are still material heretics and the communions they belong to heretical, even if the Magisterium generally opts not to use the terms.

As we can see, this apparent “radical departure” spoken of by Dr. Schreck did not really take place at Vatican II and still does not exist. If the quotation he gave seems like a radical departure to him, it is for two reasons. The first reason is an ignorance of what Tradition actually teaches. The second is because he did not read the footnotes that make sure anything that sounds new is actually grounded in tradition, which the Council Fathers were very careful to do, but which is beyond our scope. Neither helps us understand Vatican II in the spirit the Holy Father has called for.

Go to Part II.