The Road to Rome, Part IV: Why Not the Reformed Tradition?

This is the fourth of six articles relating the writer’s journey into the bosom of the one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church. Having succumbed to spiritual desolation following the rejection of his Adventist heritage, the young seeker investigates various Christian traditions, hoping to discover the Truth. Part I may be found here; Part II here; Part III here.

This is the fourth of six articles relating the writer’s journey into the bosom of the one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church. Having succumbed to spiritual desolation following the rejection of his Adventist heritage, the young seeker investigates various Christian traditions, hoping to discover the Truth. Part I may be found here; Part II here; Part III here.

Whereas my decision to forego Orthodoxy was difficult because of my deep love for Eastern Christianity in general, my decision and views regarding the Reformed tradition are difficult to write of because of my deep and profound disagreements with its fundamental doctrines.

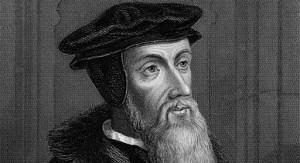

Reformed Christianity is a sort of umbrella term, I admit, but for me, Reformed Christianity is what I often term “orthodox Protestantism”: that is, the tradition of Protestantism that grew out of the thought of Luther and, perhaps more importantly, John Calvin. It must be admitted, and it must be admitted frankly, that the Reformed tradition is the only “school” within Protestantism that has theologians and scholars with the heft to match up against the doctors and saints of traditional, ancient Christianity.

We have but to mention a few of the Reformed tradition’s greatest thinkers and writers to realize as much: John Calvin, arguably the most influential theologian since St. Thomas Aquinas; Jonathan Edwards, Huldrych Zwingli, Theodore Beza, Charles Spurgeon, John Knox, John Gill, and that giant of 20th century theology (and a personal favorite of mine), Karl Barth. This is a formidable list to be sure. Even if it were Calvin alone, Reformed theology would demand engagement on account of its thorough study of Scripture.

I do not seriously encounter Reformed theology until I began to return to my Christian roots. I soon discovered that the generic evangelical Christianity that I had long disagreed with along was the fruit of Calvin’s efforts. When, as a youth, I rebelled against Christianity in a manner akin to a cornered animal, much of what I deplored flowed straight from Geneva: predestination, a wrathful God, Biblical literalism, and so on.

I do not mean to be extra hard on the Reformed tradition: this is simply an exercise in personal honesty. I am relating my own experiences and understandings, and if one wishes to view them as flawed, I am entirely open to hearing the other side of the debate.

Now, as I said before, Calvin is, for all his repulsive doctrines, a force to be reckoned with. Unlike Luther, who often succumbed to wild excursions into existential despair and crude polemic, Calvin proves himself controlled, exacting, precise, and a master of Scripture. He is, in a word, lawyerly. His words are thorough and systematic, and his monumental Institutes of the Christian Religion influence Christian thought to this very day.

Heresy, we are told, is the truth run amok. Heretics veer to extremes: whereas Ebionism said that Christ was merely human, Docetism claimed Christ was purely spiritual. And this leads me to my point: Calvin, for his part, over-emphasized the sovereignty and might of God to the point where he forgot about the humbleness of Christ, who is this same God.

I read in Calvin how “our salvation comes about solely from God’s mere generosity”1, but I do not see how this is the same as saying it comes about through the overwhelming love God has for us even as sinners. There is a tremendous difference between a God who merely allows us to live in order to save a select few and damn the rest and a God “who wills all men to be saved, and to come to the knowledge of the truth” (1 Tim 2:4).

St. John Chrysostom refutes this notion of predestination to Hell, saying that “Pharaoh was a vessel of wrath, that is, a man who by his own hard-heartedness had kindled the wrath of God. For after enjoying much long-suffering, he became no better, but remained unimproved. Wherefore he calls him not only a vessel of wrath,

but also one fitted for destruction.

That is, fully fitted indeed, but by his own proper self. For neither had God left out anything of the things likely to recover him, nor did he leave out anything of those that would ruin him, and put him beyond any forgiveness. Yet still, though God knew this, He endured him with much long-suffering,

being willing to bring him to repentance. For had He not willed this, then He would not have been thus long-suffering. But as he would not use the long-suffering in order to repentance, but fully fitted himself for wrath, He used him for the correction of others, through the punishment inflicted upon him making them better, and in this way setting forth His power. For that it is not God’s wish that His power be so made known, but in another way, by His benefits, namely, and kindnesses, he had shown above in all possible ways.”2

Incidentally, I grant that I may misunderstand, on some level, what Calvin is really pushing for here. I grant too that Calvin’s emphasis on the sovereignty of God over and above all else was a reaction, not entirely unnecessary, against abuses and errors within the Church concerning prayer to the Blessed Virgin Mary and the saints, not that intercession in itself is wrong, but that it is a doctrine that can easily be twisted and taken too far. There is a fine line here, and uninformed Catholics can easily fall into a idolatrous worship of human beings or bizarre folkish superstition, both of which are entirely foreign to what the Church teaches.

As for the freedom of the will, I do not see the teachings of Calvin supported by the testimony of the Church. Concerning Romans 9, a chapter used to support some of the central doctrines of Calvin’s thought, I again bring forth St. John Chrysostom to speak on the issue of free will:

“Here it is not to do away with free-will that he says this, but to show, up to what point we ought to obey God. For in respect of calling God to account, we ought to be as little disposed to it as the clay is. For we ought to abstain not from gainsaying or questioning only, but even from speaking or thinking of it at all, and to become like that lifeless matter, which follows the potter’s hands, and lets itself be drawn about anywhere he may please.”3

St. Augustine of Hippo, who is often invoked by Calvin in his theology, states that “God judged that men would serve Him better if they served Him freely. That could not be so if they served Him by necessity and not by free will.”4 And St. Thomas Aquinas writes that “Man has free will: otherwise counsels, exhortations, commands, prohibitions, rewards and punishments would be in vain.”5

To sum up the reason which kept me from embraciing Reformed (Calvinist) Christianity:

- Doctrines such as double-predestination, denial of free will, limited atonement, and the like, which I find contrary to the teaching of Scripture, and contrary to what we have learned through Tradition, too.

- I find that the majesty, power, might, and sovereignty of God are emphasized to the point where the overwhelming love of God is all but forgotten. God becomes not a God who loves us, but a God who simply decided to spare some of us.

What I admire about the Reformed tradition:

- John Calvin as a theologian. Though I disagree with him on very many points, he is by far one of the greatest Protestant theologians in history, and arguably the most influential.

- Reformed theology and exegesis in general is some of the best in Christendom, and has boasted many stalwarts in its ranks. Aside from Calvin, both Edwards and Barth come to mind here.

- Reformed Christianity places a great emphasis on personal piety, love of God, and diligent study of the Scriptures.

- Unlike evangelical Christianity which can often succumb to a watered-down, feel-good sort of Christianity Lite, Reformed Christianity pulls no punches, and in general, refuses to dilute its teachings.

- The devotional writing within the Reformed tradition is excellent. From Bunyan’s classic work The Pilgrim’s Progress to Spurgeon’s excellent All of Grace, there is much to had for nourishing spiritual reading. Indeed, I find that in these devotional works, Calvinism’s seemingly harsh doctrines serve the reader in a positive way, emphasizing the human need for total dependence on God’s grace.

1 – Institutes of the Christian Religion, III:XXI:1

2 – “Homily 16 on Romans”

3 – “Homily 16 on Romans”

4 – On True Religion, xiv, 27

5 – Summa Theologica, I:83:1