The Teutonic Knights

Throughout history, there have been a number of religious military orders. These orders dwelt in the shadow of the Church, shaping it through their deeds and accomplishments. One such order was the Teutonic Knights.

Throughout history, there have been a number of religious military orders. These orders dwelt in the shadow of the Church, shaping it through their deeds and accomplishments. One such order was the Teutonic Knights.

There were three major religious military orders formed during the Crusades. The most known were the Templar Knights founded around 1119, the Hospitaller Knights also founded in 1119, and the Teutonic Knights founded in 1190. These Orders were known for their medical care, chivalry, charitable works and fighting to the bitter end.[i]

The Teutonic Knights were born from the ashes of the destruction at Acre. The wounded German soldiers fighting at Acre did not receive treatment from the French nurses, because they did not understand the German language.[ii] Seeing their fellow brothers suffer, some German merchants from Bremen and Lubeck built a field hospital to house the sick and wounded German soldiers. The Germanic hospital soon joined the efforts of the Hospital of the Blessed Virgin at Jerusalem; which had moved to Acre due to Saladin taking over Jerusalem. Inspired by the works of the two hospitals many German knights joined instead of returning to Germany.[iii]

As more and more German knights stayed to support the two hospitals, talk grew of the three factions uniting. In 1190 the Germanic hospital, Hospital of the Blessed Virgin, and the German knights united an formed the Order of Teutonic Knights of the Hospital of the Blessed Virgin at Jerusalem. Strictly a religious order, Henry de Walpot became the first grandmaster of the Order. After the taking of Acre in 1191, Henry de Walpot purchased land within the city and built a church and permanent hospital for the Order.[iv]

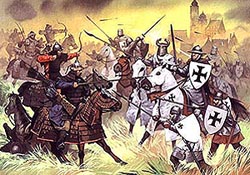

Members were classified as either knights or part of the clergy. The knights had to be born in a noble family. They not only professed the three monastic vows, but also a fourth vow to help the sick and fight for the Faith. Every member was of German birth; this was one of the requirements to join the Order. The knights wore black tunics, with white cloaks embroidered with a black cross on the left shoulder.[v] The members of the clergy did not have to be born within a noble family. The clergy were the backbone of the Teutonic Knights. Their duty was to teach the word of God within the church, to the sick in the hospital, and to the soldiers on the battlefield.

Excluding the knights and clergy the Order also had servants know as Heimlikes and Soldners. These were people who served the Order in matters dealing with religion and were handpicked by the knights to be squires. The policies of the Teutonic Knights were very strict. All the members slept in the same dormitories, which consisted of a small bed and table. Knights and clergy were expected to be at all daily church services. They could not leave the Order, nor send letters to family, unless permission was given by the grandmaster.

The title of being a knight sounds intriguing, but it was not very glamorous. The armor was very plain: gold-crested plating and ornamental jewels were forbidden. A knight was given two shirts, two pairs of boots, one surcoat, one sleeping bag, one blanket, one breviary, one knife, four horses and a squire to carry his shield and lance.[vi] They were not allowed to joust, or consort with laymen. Their hair had to be cut short, but they were allowed to grow beards. Knights were required to sleep in their clothes with their sword by their side and rise four times a night to recite offices.

The title of being a knight sounds intriguing, but it was not very glamorous. The armor was very plain: gold-crested plating and ornamental jewels were forbidden. A knight was given two shirts, two pairs of boots, one surcoat, one sleeping bag, one blanket, one breviary, one knife, four horses and a squire to carry his shield and lance.[vi] They were not allowed to joust, or consort with laymen. Their hair had to be cut short, but they were allowed to grow beards. Knights were required to sleep in their clothes with their sword by their side and rise four times a night to recite offices.

The harshest policy of all was the order’s restricted diet. A knight was not allowed to eat meat during most of November and December, or Monday, Wednesday, Friday, and Saturday of any time of the year.[vii] This is not counting the twenty fast days throughout the year. A typical Teutonic Knight diet consisted of eggs, milk, porridge, and water.[viii] Though being a knight offered absolutely no luxuries, many joined just to fight alongside their German brothers in a foreign land.

The order continued to grow by recruiting more German knights and building houses for all of its members. The Teutonic Knights took upon the duty to care for the sick, and help fight with the soldiers of Philip Augustus, King of France, and Richard Coeur de Lion, King of England stationed at Acre. Then in 1198 the Teutonic Knights were recognized as a religious military order by Pope Celestine III and Chancellor Conrad, the King of Germany. The Knights transformed into a military order mainly because Pope Celestine III called for crusades to take back Jerusalem and defend the Holy Land from the Saracens. Though the Knights were considered a military order, they did not exercise their military power until the crowning of their next grandmaster, Hermann von Salza in 1210.[ix]

Salza was described as “eloquent, affable, wise, careful and far seeing, and glorious in all his actions.”[x] With a new battle-ready grandmaster, the Teutonic Knights received many requests to drive out pagans from their allies lands. The most known invitation was sent by the Polish Duke of Mazovia, who wanted them to drive out the Prussians and in return the Knights were able to keep the land they conquered. The Prussians were described as “very savage and barbarous, and constantly committed horrible cruelties upon their more civilized neighbors, laying waste the country, destroying crops, carrying off cattle, burning towns, villages, and convents, and murdering the inhabitants with circumstances of extreme atrocity, often burning their captives alive as sacrifices to their gods.”[xi]

Hermann von Salza requested permission to engage the Prussians and in 1230, Pope Gregory IX sanctioned the crusade. The Prussian Crusade lasted close to fifty years, consisting of many bloody battles, and rebellions. Initially, the Teutonic Knights conquered the Prussians, managing to convert many to Catholicism and began encouraging German farmers to occupy the land. Then in 1242 the conquered Prussians rebelled by joining forces with Duke Swantopelk of Pomerellia who funded an army for the Prussians.[xii] This sudden turn of events caught the Knights off guard and delayed their victory in Prussia.

The Prussians fought with bravery and bested the Teutonic Knights in many battles due to their knowledge of the land, but the Knights turned to their political powers. The future Pope Urban IV convinced Duke Swantopelk to join his fellow Christian brothers and drive out the pagans from Prussian. In 1248, Duke Swantopelk cut all ties with Prussia, and in 1249 the Prussians signed the Treaty of Christburg. This treaty guaranteed personal rights to any Prussians who embraced Christianity. The newly baptized Prussians were offered opportunities to enter the monk or priest life, and converted Prussian nobles were able to become knights. The conquering of the Prussians resulted in thousands of pagans converting to Christianity and is the greatest feat the Teutonic Knights ever accomplished.

The Teutonic Knights were one of three religious military orders created to help protect the Christian people, and fight to stop Islamic expansion during the Crusades. They fought in pagan lands and converted countless to Christianity. Without the efforts of the Knights, Christianity, and more specifically Catholicism, would never have spread throughout the lands of Russia. Today the Teutonic Knights are a symbol of sacrifice. They are a poetic symbol of countless knights who died for the progression of the Faith.

[i] Friedrich Heer, The Medieval World Europe 1100-1350. (Cleveland and New York: World, 1962), 103.

[ii] Teutonic Knights: Their Organization And History. World History Project, USA, 2006. <http://www.history-world.org/teutonic_knights.htm> (Accessed 8 December, 2012). Hereafter Teutonic Knights.

[iii] Steven Runciman, The Kingdom of Acre and the Later Crusades. Vol. 3. (New York, New York: Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge, 1993), 98.

[iv] Teutonic Knights.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] John L. Papanek (edit.), Time Frame AD 1200-1300 The Mongol Conquests. (Richmond, Virginia: Time-Life, 1993), 121. Hereafter Papanek followed by page number.

[viii] Ibid.

[ix] Papanek, 118.

[x] Ibid.

[xi] Teutonic Knights.

[xii] Marcel Dunan (edit.), “The Baltic Crusade.” Larousse Encyclopedia of Ancient and Medieval History. (New York: Harper & Row, 1963), 350.