Today’s Three-Parent Kids Are Not the Same As Tomorrow’s Three-Parent Kids

Many people are not aware that there are already about two dozen kids in the United States that have been genetically modified. A recent headline exclaims that “The World’s First Genetically Modified Babies Will Graduate High School This Year.” This is true.Nearly 2 decades ago, Dr. Jacques Cohen of the Institute for Reproductive Medicine and Science of St Barnabas in New Jersey genetically altered the eggs of infertile women and created around 30 genetically-modified children. Cohen used a technique called “cytoplasmic transfer” to “rejuvenate” an infertile woman’s eggs by injecting the cytoplasm of another woman’s healthy egg. Factors inside the cytoplasm help the infertile woman’s egg in fertilization.

Many people are not aware that there are already about two dozen kids in the United States that have been genetically modified. A recent headline exclaims that “The World’s First Genetically Modified Babies Will Graduate High School This Year.” This is true.Nearly 2 decades ago, Dr. Jacques Cohen of the Institute for Reproductive Medicine and Science of St Barnabas in New Jersey genetically altered the eggs of infertile women and created around 30 genetically-modified children. Cohen used a technique called “cytoplasmic transfer” to “rejuvenate” an infertile woman’s eggs by injecting the cytoplasm of another woman’s healthy egg. Factors inside the cytoplasm help the infertile woman’s egg in fertilization.

When Cohen injected the cytoplasm of the healthy egg, it contained mitochondria from the donor egg. Those mitochondria have DNA from the woman who donated that egg called mtDNA. So the after that hybrid egg was fertilized, the resulting children had the DNA from 1 man, and 2 women. A genetic modification that any girl would pass onto her offspring since mitochondria are inherited from the mother only.

In 2002, the Washington Monthly did an in depth story on “cytoplasmic transfer” and Dr. Cohen where it was reported that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) ordered Cohen and other fertility clinics to stop performing cytoplasmic transfer.

That seemed to be the end of creating children with three-genetic parents until “mitochondrial replacement” also called the “three-parent embryo” technique, came along recently as a way to “prevent” the inheritance of mitochondrial disease caused by mutations in the mtDNA.

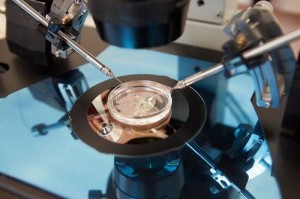

Mitochondrial replacement is a more invasive technique where instead of simply injecting cytoplasm into an egg to help with fertilization, the egg is taken apart. The nucleus of an egg with defective mitochondria is removed and placed into an egg with healthy mitochondria. That radically-altered egg is then fertilized. Like cytoplasmic transfer, this creates an embryo with the genetic material from three people.

Now that the United States and the United Kingdom are seriously considering moving forward with mitochondrial replacement, the children of cytoplasmic transfer are under scrutiny to see if they are healthy and normal. The New York Times did a glowing piece on 13 year-old Alana Saarinen, conceived with cytoplasmic transfer, that concludes:

Mrs. Saarinen, a hairdresser in suburban Detroit, believes the case for a new kind of fertility treatment is already clear. Her daughter Alana — athletic, smart and slim — has never been sick with anything worse than the flu.

“I’ve got the living proof every day,” she said.

The message is clear, since Alana, at 13, is healthy then we are clear to move forward with mitochondrial replacement. By all means, let us begin to genetically modify our children, grandchildren and great-grand children because Alana is “athletic, smart and slim.”

In all seriousness, there are several problems with this logic, or lack there of:

1. Alana, as sweet as I am sure she is, is an anecdote. We cannot base any decision about the safety of having three genetic parents on her smarts, her academic record, or her weight. What about the other children? The Washington Monthly story reveals that another cytoplasmic transfer child has been diagnosed with “pervasive developmental disorder.”

2. Alana is only 13 and has yet to teach adulthood or have children of her own. A paper published in Science urged caution in moving forward with mitochondrial replacement because many effects of a mismatch between nuclear and mtDNA in animal studies are not observed until adulthood. We also have no idea how Alana’s genetic engineering will affect her children.

3. Even if Alana and all the other cytoplasmic transfer children and their children are perfectly healthy for their entire lives, that says nothing about the future of mitochondrial replacement kids. The two techniques are fundamentally different. In cytoplasmic transfer, some extra cytoplasm is injected into the egg leaving it intact. In mitochondrial replacement, the egg is taken apart having a nucleus removed and then replaced, a much more invasive and destructive technique.

Mitochondrial replacement has more in common with cloning, where the nucleus of an egg is also removed and then replaced, then it does with cytoplasmic transfer. We all know about animal cloning horror stories including dogs that turned out greenish-yellow or were the wrong sex. Cloning trials in agricultural animals in New Zealand were halted because an unacceptable number of the cloned animals and their gestating mothers had to be euthanized.

The invasive nature of mitochondrial replacement is what caused Dr. Paul Knoepfler, stem cell researcher at UC Davis School of Medicine, to comment on Alana’s story that this technique will “inevitably” create children with “chromosomal defects” and “developmental problems.”

I am glad that Alana is so far happy and healthy, but she in no way proves that the children of mitochondrial replacement will be as well.