Trespassing Trial Humbles Abortion Mill

It is said that Planned Parenthood usually wins in court. But not always. Last month, thanks to a display of courage by Michael Ferman, abortion “rights” did not, for once, trump all other considerations.

Ferman, age 34, is a member of the Knights of Columbus, and a former student of mine. I have known him and his family for many years, and I believe the remarkable event in which he played the primary role deserves to be aired. A few weeks after the trial recounted below, Mike began his year as a postulant residing at the Franciscan Friary in Ft. Wayne, Indiana.

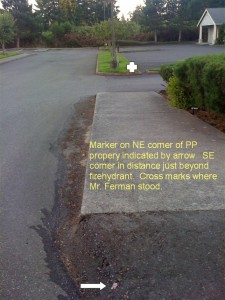

Mike’s trial was for 2nd degree trespassing, at most a few feet onto Planned Parenthood property in Kitsap County WA (due west of Seattle). The trespassing charges concerned Mike’s having advanced onto the grass at the outer edge of the PP parking lot. PP has for years been peeved by our picketing their abortion mill. They singled out Mike as particularly irksome because of his long-term dedication and sometimes solo vigils at the perimeter of their property.

As Glenn Stockton who coordinates pro-life action at the PP facility describes Mike: “All of us in the Kitsap County pro-life community have witnessed Michael Ferman’s zealous activities of spreading the truth to the uninformed regarding the ongoing slaughter of the unborn in Kitsap County. Instead of being criticized for his peaceful actions on behalf of the ‘least of these,’ our unborn brothers and sisters, his actions should be emulated.”

No wonder PP jumped at their opportunity and called 911 as Mike was counseling a woman to spare her baby. When the responding police officer asked if they wanted to press charges, the PP person in charge answered unhesitatingly in the affirmative.

The legal process neared its final phase in August with consultation between the Deputy Prosecutor, Ms. Lael Carlson and Mike’s court appointed defense attorney, Jenease LaCross. Under a plea bargain arrangement negotiated by the two attorneys, Mike was to receive a $200 fine, plus a year’s probation under deferred sentence provisions. After a year’s “good conduct,” Mike would be allowed to change his plea to not guilty. The court would then dismiss all charges.

Ms. LaCross, suggested to Mike — not quite imperatively — that he take the offer, as it was the best she could possibly get for him. Otherwise, said she, Mike risked up to 90 days in jail if convicted by the jury, although she suspected ten days of home confinement with an ankle bracelet was more likely.

During pre-trial consultation, LaCross downplayed my own reference to the possibility of jury nullification. It was an old principle, she admitted; but defense attorneys were forbidden by the standards of the bar to suggest to jurors that they could simply disregard the law in favor of fairness and justice. LaCross pointed out that even if a few stalwarts did create a hung jury, the mistrial would not prevent the prosecutor from retrying the case.

Mike consulted with me, his mother, two other friends, and his lawyer. He was torn between principle and pragmatism, between what he called “the best option versus the easiest.” If he took the offer, his plan was to work off the $200 fine with community service as he had done in the past with traffic tickets.

I suggested that before deciding he might watch the PP video of the incident. LaCross got access to it; and after viewing the video, which showed him on the grass adjacent to the parking lot, Mike decided to go with a jury trial. “I’ve done nothing wrong,” was his bottom line.

The jury pool of 26 citizens selected by lot were already in the courthouse, waiting in a holding-room. Before they were even seated for the jury selection process, I discovered that in Judge Marilyn G. Paja of the Kitsap County District Court we were dealing with a dreary bureaucrat. Mike told me later about being put off by the atmosphere of “play acting,” with machine-like communication consisting of memorized stock phrases in lieu of natural human interaction.

For example after I identified myself to Judge Paja and offered to show my press pass, I got into a procedural dispute over what direction I should face once the jury entered the room. The concern, announced Her Honor, was that one of the jurors might be able to read what was on my computer screen. I offered to sit sideways toward the front of the room, but she cited safety concerns for lawyers traversing the 3 or 4 foot wide passageway between us. I offered to sit in the rear of the room with my screen facing the back wall, but after wrangling over the issue of electrical outlet location, she called in a staff technician regarding safety concerns if I used an extension chord. Finally, Judge Paja issued her ruling. As soon as the jurors arrived I would have to go battery power only.

I’m guessing that the delay cost taxpayers in excess of $100 worth of time spent to resolve the logistics of this “problem.” It would have been so easy to settle with a little human flexibility. Aristotle noted long ago that man is the most adaptable of animals. It struck me as yet another example — slight but typical in postmodern society — of how human will is bound and the intellect dulled by mindless bureaucratic regulations.

Once the jury arrived, Judge Paja began reiterating pat formulas over and over, ad nauseum, so as to weary any juror, not to mention the defendant and his attorney. Included was Judge Paja’s repeated instruction to the jury pool to follow only the law, not personal opinions of what was fair or just, or whether the charge was vindictive and picayunish. Thus did she program the jury to be bureaucratic, rather than — God forbid!–– act as a populist mediator between the government and the citizen.

Once the jury arrived, Judge Paja began reiterating pat formulas over and over, ad nauseum, so as to weary any juror, not to mention the defendant and his attorney. Included was Judge Paja’s repeated instruction to the jury pool to follow only the law, not personal opinions of what was fair or just, or whether the charge was vindictive and picayunish. Thus did she program the jury to be bureaucratic, rather than — God forbid!–– act as a populist mediator between the government and the citizen.

Soon, Deputy Prosecutor, Ms. Carlson, took the floor and began questioning the jury pool. How, she asked, would they define trespassing? “Crossing a boundary,” someone proposed. “Almost like breaking and entering,” said another.

Carlson continued to probe the jury pool about trespassing’s definition. Responses ranged from entering a house without permission, entering the yard, or stepping on property outside of the public right of way. Exceptions, they thought, would include the Postman delivering mail, Boy Scouts selling popcorn, and religious solicitors, like Seventh Day Adventist missionaries knocking on the door. It was opined that the latter could become trespassing if a respectful retreat was not forthcoming after being asked to leave.

During voir dire proceedings, one prospective juror identified herself as currently a Planned Parenthood worker. She indicated that she considered protestors upsetting for many reasons, and admitted to uncertainty as to her ability to be fair and impartial. Another prospective juror was a former protestor himself on unidentified issues(s). He suggested that it was like politics where voters should “step back from” their own spiritual training, and decide issues “objectively.” (Hmm, ?#!) Another juror voiced her disdain for using the court system to extend pro-life protests to a wider audience. Still another woman formerly involved with Planned Parenthood expressed doubts about her ability to be fair to both sides.

After selection of six jurors (not twelve), the Prosecutor proposed to call a Mr. Denis as a witness. Denis is a former owner of the building before PP acquired it. For the past three years he has worked as a maintenance man there, and also as director of security.

Judge Paja first had Mr. Denis interrogated by the two attorneys, with the jury absent. The Prosecutor sought to admit his testimony as to the location of the property line. Denis’ information, it turned out, was based on what his predecessor on the job had told him. Ms. LaCross, objected that the testimony was therefore hearsay. It should not be heard by the jury, she argued.

On day two of the trial, Judge Paja sustained LaCross’ objection, and ruled that the testimony by Mr. Denis was hearsay, was too uncertain, and was therefore inadmissible. Next Prosecutor Carlson tried to bring forward maps, hurriedly secured from the Assessor’s office across the street. Since they were uncertified copies, they were also ruled inadmissible.

At this point, Carlson seemed utterly at a loss how to proceed, and Judge Paja told her, in what struck me as a motherly way, “I can’t tell you what to do.” The Prosecutor then announced that she could not go forward. On behalf of the Prosecutor’s office, Carlson asked that the charge be dismissed without prejudice. Judge Paja signed the order clearing Mike shortly before noon, August 21st.

In a huddle just outside the courtroom, six or seven gloomy PP employees and supporters were overheard lamenting the result. They were discussing how in future the boundaries should be ascertained officially and clearly marked. On the sidewalk outside the courthouse, quite a different group gathered for prayer. A half-dozen of us stood and offered up a Glory Be. Thus did right prevail, and Planned Parenthood suffer a well-deserved humiliation.

Impressed with his exercise of the cardinal virtue of Fortitude, I interviewed Mike Ferman a day after the trial. I asked about the stress he had felt. Even the interrogation by his own attorney produced anxiety, he said. He elaborated on how stressful it can be to introspect, and to second guess yourself. Going to Confession would be a case in point, he said. Another source of stress for Mike was grappling with the dissonance between the law of man and the law of God. Also stressful was the effort to resolve the tension between zeal and prudence.

Mike did indicate, I’m heartened to say, that he was influenced by my words encouraging him to take the high road of principle, even as his attorney was pushing him in the pragmatic direction. Mike said he saw it as somewhat similar to the difference between an “A” and a “C” on a term paper. “Why settle for mediocrity, he asked.”

Mike stated that we have a duty to become activists, especially when circumstances, like his own unmarried state, put Christians in a better position to take more risk. He argued that the Gospel does not call for us to be cowards. We need to be bold; God will take care of us, Mike said. “You’ll never be a saint by being a coward.”

He added that the fear of publicly engaging such a controversial issue has to be overcome, “because it is necessary to stand up for the weakest among us,” and assist the women and young girls being lured into the mill of murder. Whether they go to Planned Parenthood for abortions, or for condoms, pills or other contraceptive assists, no one should do business with that vile establishment, Mike insisted.

In conclusion, kudos to Mike for resisting the impulse to choose the course that was safer and easier. As he said later, the plea bargain offer was tempting, because $200 was not a lot of money and it was a pretty safe choice. It was “probably the percentage play,” or the easiest, and the “smart move” legally. Instead he chose the high road, “yielded to the Grace of God,” and hazarded the peril of 90 days in jail; also the considerable stress that would have entailed.

Applicable here is the venerable maxim of the American Admiral, John Paul Jones: “he who will not risk, cannot win.”*

_____

* John Paul Jones, letter to Armand de Kersaint, 1791. “The rules of conduct, the maxims of action, and the tactical instincts that serve to gain small victories may always be expanded into the winning of great ones with suitable opportunity; because in human affairs the sources of success are ever to be found in the fountains of quick resolve and swift stroke; and it seems to be a law inflexible and inexorable that he who will not risk cannot win.”