What Is Social Justice?

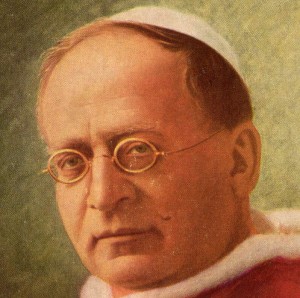

When last we met, we looked at Rerum Novarum, Pope Leo XIII’s encyclical which inaugurated modern Catholic social thought. We now continue our magical mystery tour by turning our attention to Pope Pius XI’s Quadragesimo Anno of 1931. Before we explore the major themes of this incredibly important document, however, it would serve us well to examine a term that Pope Pius formally introduced into the Church’s social doctrine, but which is the source of much confusion, particularly in the United States. What, exactly, is “social justice?”

When last we met, we looked at Rerum Novarum, Pope Leo XIII’s encyclical which inaugurated modern Catholic social thought. We now continue our magical mystery tour by turning our attention to Pope Pius XI’s Quadragesimo Anno of 1931. Before we explore the major themes of this incredibly important document, however, it would serve us well to examine a term that Pope Pius formally introduced into the Church’s social doctrine, but which is the source of much confusion, particularly in the United States. What, exactly, is “social justice?”

Political commentator Jonah Goldberg, in his New York Times bestseller The Tyranny of Clichés, identifies “social justice” as one of several clichéd terms which short-circuit political debate. He argues that it has come to mean simply “goodness,” as defined by whoever happens to be speaking, and if you disagree, then you’re against social justice, which means you are for “badness.” Even when specifics are given by active political groups, they are not always universally accepted good things. One particularly humorous example is from the Green Party, which lists secession of the State of Hawaii as a requirement of social justice.

Even for those of us who are fully immersed in the social doctrine of the Church and use the term “social justice” on a regular basis, Goldberg’s point can be well-taken. And, to his credit, he does explore the historical roots of the term in the Catholic intellectual tradition. Goldberg also notes that, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, “social justice” is a synonym for “distributive justice,” another term we find explored in the Catechism of the Catholic Church.

Goldberg correctly asserts that for many, particularly on the political Left, social justice is merely the pursuit of the good, whatever that might be for each person or group. It is also true, however, that for many on the political Right, social justice simply means the pursuit of the bad. It is a fundamental law of the universe that if you write or speak to an audience of at least a few dozen people about economic or social justice, you will be accused of believing that the government should redistribute wealth and ensure that people who refuse to work live lives of material comfort at the expense of the productive members of society.

Of course, that is not what the Church means when she speaks of social or distributive justice. In fact, a quick look at the Catechism debunks that idea. Social justice is treated most directly in paragraphs 1928-1948 and 2426-2435, immediately following the section on the social doctrine of the Church (the entire discussion falls under the Seventh Commandment, “You shall not steal”). In paragraph 2427, it is made clear that work is a duty that is bound up with our dignity as human beings. That oft-quoted statement from St. Paul, frequently used to “debunk” the idea of social justice (“If any one will not work, let him not eat”) is here cited as an essential part of the Church’s understanding of social justice.

Let us be very clear on this point. Social justice has nothing to do with negative consequences a person suffers due to their own bad choices. If a man has access to honest employment at fair wages sufficient to support himself and his family, and he refuses to work, the resulting suffering is not a question of social justice. This clarification should make clear what would be violation of justice in economic terms. If the same man is more than willing to work, but is unable to find honest employment, or if the wages he can receive are inadequate to meet his and his family’s basic needs, that is an injustice. He has a duty to work to support his family, and his human dignity demands that he do so. The fact that he cannot achieve that is an injustice, due to no fault of his own.

Distributive justice, the economic component of social justice, does not mean that each person is entitled to a fair share of the produced wealth of the community, regardless of his or her input. It does, however, mean that he or she is entitled to compensation equivalent to his or her contribution. The injustice that was so apparent to Pope Leo and Pope Pius was that so many were contributing their labor to the production of great wealth and receiving barely subsistence-level wages while the employers were gaining vast fortunes.

To compound the injustice of these circumstances, the problems were largely dismissed by the rich and the powerful, as the result of immutable economic laws. Pope Pius does not condemn the accrual of wealth through honest and just means. He does, however, explicitly condemn the defense of manifest injustice as a natural necessity and the insistence by the wealthy that they had no moral obligation to better the lives of the working class except through whatever charitable contributions they might happen to make.

So far, we have only looked at the economic side of social justice. Of course, we can also acknowledge that there are “structures of sin” that go beyond personal moral choices and have no direct economic context. The widespread legal and cultural promotion of abortion is the clearest example. Few of us would object to the idea that the prevalence of abortion is an injustice at the societal level. However, the challenge to many of us who come from the political Right is acknowledging the need to address economic injustices (and I do mean us; for a long time, I denied the concept of social justice in economics).

Having hopefully cleared away some prominent misunderstandings which could hinder our appreciation of Pope Pius XI’s contribution to Catholic Social Teaching, next time we take take a closer look at the teachings found in Quadragesimo Anno.